|

US Attorney General Jeff Sessions, referenced rising rates of violent crime in a recent speech. Indeed, the murder rate increased 11% in 2015, particularly in cities like Baltimore, Memphis, Milwaukee, and Chicago (Gass, 2017). Sessions’ background is an important shaper of his response to the recent uptick in violence. Sessions was a prosecutor in the 1980’s, and his recent critics argue that his approaches to fighting crime, have not moved far beyond those of the 1980s (Jackman, 2017). For example, in a March memo, Sessions, quite arbitrarily ordered prosecutors to seek the harshest penalties possible (Cevallos, 2017). It is expected that sessions will take a hard line on mandatory minimum sentencing as well. However, it would be difficult to find evidence that this measure will bring those levels down.

Disregard for Scientific Evidence What has not been noted is what Sessions didn’t say. In his speech, Mr. Session’s merely mentioned the need for prevention in a single sentence, yet after the stand-alone statement, he quickly abandoned the idea and returned to his focus on incarceration. What scientific evidence tells us is that treatment, reentry programs (i.e. job training), and prevention are far more effective approaches to fighting drug crime than incarceration (Gass, 2017; Kerman, 2017; Rhodan, 2017). Moreover, the Federal Sentencing Commission and the National Research Council indicate that lengthy prison sentences are ineffective crime control methods (Kerman, 2017). The US criminal justice system, based on its spending, continues to favor punishment over rehabilitation and prevention (Cevallos, 2017). Mr. Sessions memo and speech contributes to the already existing punitive imbalance. What motivates a policy so lacking in 21st-century logic? Who benefits? Who Benefits Among the direct beneficiaries is the $20 billion-dollar prison industrial complex. Black people’s presence in prisons across the country already fuels the industry in the form of jobs created, building contracts, telephone services, bussing services, medical services, and purchase of products and services (Weatherspoon, 2014). As incarcerated populations are not counted among the unemployed and mostly vote democratic, Sessions policy is likely to undermine democratic voting power while also allowing the Trump administration to claim economic improvement by hiding a significant portion of its otherwise unemployed population (for example, most Black men in prison were unemployed at the time of incarceration) (Stewart, 1994). What Can Black People Expect With the implementation of Sessions’ order, Black people must have expectations based on historical precedent and scientific evidence. Racism is endemic to sentencing, therefore Black people can expect to absorb a disproportionately larger share of the sentencing increases that Sessions has called for. For example, a Washington State Task Force on Race and the Criminal Justice System found that Black offenders received harsher sentences for drug offenses than similarly situated Whites (Weatherspoon, 2014). Prosecutors seeking the harshest sentencing may also result in overworked, inexperienced public defenders compelling more Black defendants to admit to crimes they did not commit to negotiating for shorter sentences. It is also likely that harshest penalties and increased mandatory minimums will result in more fragmented families as judges and prosecutors will have less discretion to be lenient to certain offenders based on the circumstances of their offenses. Finally there is what Michelle Alexander calls the final phase of the mass incarceration process, which includes punishments that isolate Black people from the mainstream economy. She calls this final phase, invisible punishment, which begins after prisoners are released from prison. Largely outside of public view, they prevent convicted offenders from integrating into mainstream society. In this phase, they are legally discriminated against by way of denial of employment, housing, education, and public benefits (Alexander, 2010). November 6, 2018 As midterm elections approach it will be critical that Black voters demand that elected officials have policies that include a commitment to treating drug abuse as a public health issue. It is time to convert popular Black resistance movements into a viable political party in the tradition of the Gary Convention. Moreover, officials that Black people vote for must have policies that place emphasis on reentry programs, prevention, and drug treatment…… However, in a White supremacist society it is not likely that this will happen speedily at levels that will provide measurable protection to the Black community from the regressive policies of the Trump administration. Recognizing this may compel Black public health professionals and criminal justice professionals to develop independent community-based crime prevention programs, job training programs, and drug treatment programs customized for Black people. Independent Black professional innovation is the only reliable failsafe for the Black future. Attorney general jeff sessions delivers remarks on violent crime to federal, state and local law enforcement. (2017). States News Service . Cevallos, D. (2017). Jeff sessions takes wrong turn on crime. CNN Wire. Gass, H. (2017). Why some worry Jeff Sessions' crime-fighting approach is out of date. The Christian Science Monitor,. Jackman, T. (2017). Sessions takes federal crime policy back to the '80s. The Washington Post. Kerman, P. (2017). Tough on crime still racist. USA Today, Rhodan, M. (2017). Sentencing reversal angers both sides. Time, 189(20), 11. Stewart, J.B. (1994). Neoconservative attacks on Black families and the Black male: An analysis and critique. In R.G. Majors and J.U. Gordon (Eds.), The American Black male. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers, pp. 40-68. Weatherspoon, F. (2014). African-American males and the U.S. justice system of marginalization: A national tragedy. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

0 Comments

Written by Serie McDougal

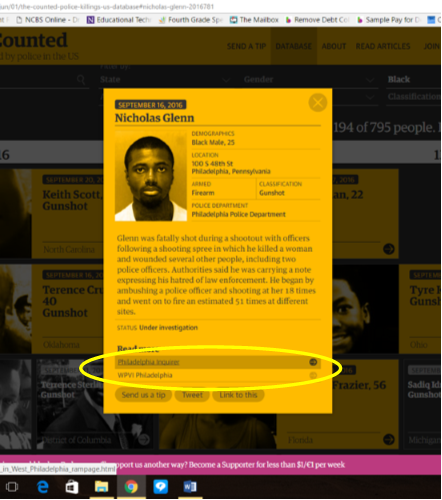

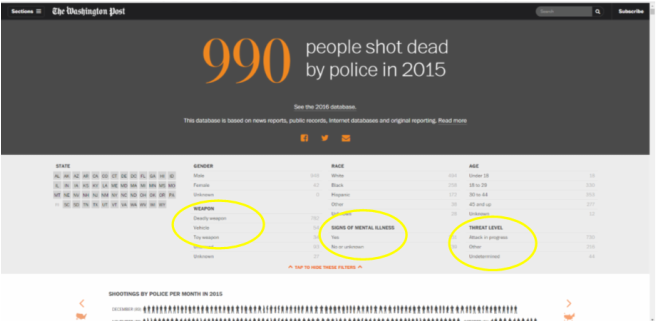

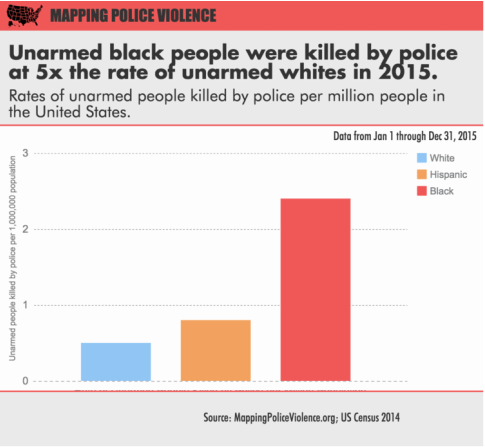

Recently, Tom Weathersby of the Mississippi state House of Representatives proposed a bill. It recommends a new law that would impose fines and psychological counseling for people who sag their pants. This article contains thoughts about what this bill means for young Black males. To be in violation of the law, one has to sag their pants in ways that expose underwear or body parts in an “indecent or vulgar manner.” The ambiguity of this phrase invites what is known as aversive racism. The theory of aversive racism assumes, for example, that in situation where evaluation criteria is unclear, Whites will typically treat African Americans with negative bias (i.e., stop and frisk laws) (Dovidio, & Gaertner, 2000). This proposal could be, at once, the continuity of White cultural racism and trickle down cultural chauvinism in the time of Donald Trump. Cultural chauvinism, goes beyond the recognition of cultural difference, toward to punishment of difference and elevation of one’s own cultural preferences as a default societal standard. This has been the White supremacist orientation toward African American styles for hundreds of years. Yet, in a way that might be considered strange, Whites have described African American cultural styles as wild, barbaric, and indecent (blues, rap, Ebonics, dance), yet also expressed deep admiration of those styles, expressed through imitation, appropriation, and commodification of them. The cultural chauvinism that President Donald Trump has shown the world, may be trickling down to the state and local levels or simply emboldening already existing White cultural racism. Tom Weathersby’s prejudice against certain styles of clothes, such as sagging pants, will be institutionalized into law if the bill is passed. But what do clothes mean? Generally, clothes can simply represent style, but they can also be used to tell elaborate stories about culture and identity. African Americans have used clothing to symbolize, attitudes, values, interests, affiliation, pride, and identity (Andrews & Majors, 2004, p.326). From zoot suits to traditional African garments, African American men have developed unique ways of dressing to express themselves and distinguish themselves (Franklin, 2004). During slavery, Black men used the clothes available to them to create their own styles. This is, in part, a way of expressing themselves on their own terms and enhancing self-image while society attempts to make them invisible (Majors & Billson, 1992; Franklin, 2004). Black male clothing trend-setting has taken common items such as stocking caps or do-rags, bandanas, and plain white t-shirts to the point that they have been commodified and transformed into mainstream symbols of masculinity. Yet, their styles have also been criminalized and marketed. The hip hop industry has garnered millions of dollars by transforming Black male clothing styles into designer apparel. Sagging pants is one of many culturally influenced behaviors such as playing the dozens, clothing styles, rapping, and using slang. However, for Black males these are not just innocent stylistic choices, they can be life-threatening (for example, Trayvon Martin). Black parents recognize this and send messages to their sons in preparation for bias, which is a racial socialization practice that between two-thirds and 90% of African American parents engage in. These parents make their children aware of racism and prepare them with strategies for how to handle it. They may engage in telling their sons to “be on time, to avoid wearing sagging pants or hoodies, and to work extra hard” (Brewster, Stephenson & Beard, 2014, p.97). They do this because they know that their sons will be misjudged in society’s institutions. Kunjufu (2009) explains that when some Black males behave in accord with their culture, their teachers perceive their shoulder shrugging, baggy clothes, sagging, attitudes, and direct eye contact as threatening, noisy, disrespectful, intimidating. It is important that Black communities demand that service providers interrogate their assumptions about Black males and where those assumptions came from. In addition to interrogating their beliefs about Black males, they need culturally responsive policy making. To continue with the traditional approach of training Black males to adjust themselves in preparation for bias is placing too much pressure on them and not social institutions and it can lead them to internalize negative attitudes about themselves and other Black people. Brewster, J., Stephenson, M., & Beard, H. (2014). Promises kept: Raising Black boys to succeed in school and in life. New York, NY: Spiegel & Grau. Dovidio, J., & Gaertner, S. (2000). Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science, 11(4), 315. Franklin, A. J. (2004). From brotherhood to manhood: How Black men rescue their relationships and dreams from the invisibility syndrome. New York: Wiley. Graham, A., & Anderson, K. (2008). “I have to be three steps ahead”: Academically gifted African American male students in an urban high school on the tension between an ethnic and academic identity. The Urban Review, 40(5), 472-499. Majors, R., & Billson, J. M. (1992). Cool pose: The dilemmas of black manhood in America. New York: Lexington Books. Written by Sureshi Jayawardene Ida B. Wells once said, “those who commit the crimes write the reports.” Today, the glaring truth of Wells’ words reverberate throughout the Black community as the death toll steadily rises, while law enforcement officers face minimal charges often going without a conviction, and the criminal justice system remains the same well-oiled machine. As the Afrometrics article, “The False Premise of ‘Not Working’” from April 2015 pointed out, the system is working. In fact, it’s working rather well. In the late 19th century, Wells was concerned about the powers that would narrate and subsequently find ways to justify the extrajudicial killings of Black people. She dedicated her life to bringing attention to the dominant discourse, hegemony and American spirit underlining these killings. An avid activist and Black political theorist, Ida B. Well’s words are so relevant today, not simply because of the ceaseless gratuitous violence against Black people, but also because of how documentation of such violence is taking place. Or, not taking place. It is quite ironic, but not writing reports is as good as writing a report that does everything to avoid incriminating the murderer. The Reports They Don’t Write In October 2015, at a US Justice Department summit on violent crime reduction FBI director James Comey stated, “It is unacceptable that the Washington Post and the Guardian newspaper from the UK are becoming the lead source of information about violent encounters between [US] police and civilians. That is not good for anybody.” Comey claimed it was “embarrassing and ridiculous” that entities independent of the federal government had been more efficient in this data collection and that they made it easily accessible to everyone. However, a year prior to that, a few days before Michael Brown’s violent death, the most reputed crime-data experts in DC determined they could not accurately count how many Americans die each year at the hands of police, so, they put an end to counting altogether. Data Compilation Since we are the victim and we fight daily to avenge those who are killed, we have to be the ones to compile the evidence and put together the reports. We have to compose our own narrative so that it will ultimately aid us in our collective action to bring down the forces that oppress us. Today, the FBI claims to know little more than a year ago when Comey made his embarrassing admission. But, there is plenty data, as Kia Makarechi, story editor and associate director of audience development at Vanity Fair, reported in July this year. He writes, “eighteen academic studies, legal rulings, and media investigations shed light on the issue roiling America.” The Guardian, through a crowdsourced project, The Counted, has created an extensive searchable database of police killings in the US. Here you will find amassed significant detail about each police involved death of a civilian from 2015. For each case, you can also find links to news and media coverage of the incident: This database also has a “send a tip” tab encouraging vigilance and awareness among citizens to report any helpful information regarding these incidents. In a separate effort, the Washington Post tracked the number of people killed by the police in just the year 2015. The data gathered includes demographic information for each victim and also notes conditions such as “signs of mental illness,” “threat level," and "weapon.” According to Mapping Police Violence, in 2015 alone, unarmed Black people were killed by police at 5 times the rate of unarmed White people. This organization presents data in easy-to-digest infographic form. Readers can find a map of police violence across the nation, images that portray the rate of conviction of police officers for their crimes, the “most dangerous police departments,” police violence by city and state, as well as annual reports. The organization also urges visitors to the website to demand political action. Other databases also exist. They include: Fatal Encounters and the Facebook compilation Killed By Police. Finally, a database specifically focused on African American deaths at the hands of law enforcement, Operation Ghetto Storm, which is supported by the Malcolm X Grassroots Committee issued a report in 2014. This was actually an updated version of their 2012 report which details their organizational mission and objectives, and tallies the number and frequency of extrajudicial killings of Black people. The author, Arlene Eisen, links present day violence against Black communities to the long history of oppression and subjugation endured by African Americans. Furthermore, Eisen underscores that the model of protest immediately after a police shooting is insufficient to take down the system that sustains this oppression. She describes necessary steps to act against the continued war on Black people, including self-defense training and organization in the Black community, but also building broad alliances with other oppressed groups to work together against the continuing modes of violence on our communities.

In addition, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled last week in the gun conviction case of Jimmy Warren that the fact that Warren ran away should not be used to further incriminate him. The court said that according to state law, individuals had the right to not speak to police and even walk away from them if they were not being charged with anything. The justices further declared, “…flight is not necessarily probative of a suspect’s state of mind or consciousness of guilt. Rather, the finding that black males in Boston are disproportionately and repeatedly targeted for FIO [Field Interrogation and Observation] encounters suggests a reason for flight totally unrelated to consciousness of guilt. Such an individual, when approached by the police, might just as easily be motivated by the desire to avoid the recurring indignity of being racially profiled as by the desire to hide criminal activity. Given this reality for black males in the city of Boston, a judge should, in appropriate cases, consider the report’s findings in weighing flight as a factor in the reasonable suspicion calculus” The court cited evidence from a 2014 ACLU of Massachusetts report about the disproportionate levels of police stops experienced by Black people. The court also cited evidence from Boston police data on field interrogation and observation (FIO) to further support this. Our Own Vigilance and Racial Protectionism As a parent of a Black son, I often find myself frustrated and helpless that as his mother any amount of protection I afford my son will not safeguard him from experiencing racist violence. As we have seen in recent years, Black people are being killed by police for simply being. A new study from the Yale Child Study Center found that ‘implicit bias’ affects how teachers treat African American males from as young an age as 4 years old. Implicit bias refers to unconscious prejudices and stereotypes that influence interaction with different people. The researchers examined “the potential role of preschool educators’ implicit biases as a viable partial explanation behind disparities in preschool expulsion.” Researchers found that when expecting challenging behaviors, educators looked longer at Black children, particularly Black boys. The findings also suggest difference in implicit biases based on teacher race. The findings of this study demonstrate the deep-seated nature of racist thinking and ideas. It is clear that teachers’ hyper-vigilant gaze at Black boys is influenced by the dominant culture’s racist narrative of Black criminality. However, to call something implicit and unconscious is dangerous, because this suggests that people have little to no control over the “unconscious” and that everyone is “biased” and “prejudiced” to some varying degree. In turn, there is little that comes in the form of a critique of the overarching dominant culture that sustains the real culprit: racism. While the term implicit bias can be problematic because it deflects accountability and transparency for racism and its consequences, the results of this study are useful for Black parents making decisions about their children’s education, everyday racial socialization, and overall safety from racial violence throughout the lifespan. Taking action regarding the impact of racial profiling and presumptions of criminality at the preschool age might aid Black parents and larger community networks in preventing our loved ones from being featured in the above databases. Written by Serie McDougal

One of the unsung solutions in Black higher education is the role that Black Culture Centers (BCC) play in the college experiences of Black students. This is especially true for Black students on campuses, where they are underrepresented and/or in the numerical minority. On these campuses Black students face marginalization, social, isolation, underrepresentation in curriculum, and lack of cultural understanding. This can result in diminished sense of school-pride and spirit, and sense of belongingness. According to Patton (2006) Black students explain that they are sometimes stereotyped and treated in one of four ways: “as the spokesperson for all black people; as the academically underprepared beneficiary of affirmative action; as the angry, defensive minority; or as the invisible student” (p.2). In one of the few studies on the impact of Black Culture Centers, Patton (2006) interviewed students who participated in BCCs. She explains how BCCs benefit students in many ways, including increased opportunities for involvement and preparation for student leadership, a richer understanding of their community, enhanced development of their black identity, increased pride in their shared history, and an enrichment of strategies for thriving in college. INVOLVEMENT Students reported that the Black culture center’s activities and workshops taught them leadership and organization skills. They also provided them opportunities for leadership, and served as a pathway to membership in campus wide organizations. COMMUNITY Students reported that the Black culture center provided them with culture specific services that were geared toward their needs and interests and styles. The center provided them with an opportunity to form social relationships with other students and faculty and staff. They felt that faculty and staff at the centers were like mother and father figures and their peers, like family members. HISTORICAL PRIDE AND IDENTITY Students reported that the Black culture center provided them a place to learn about their culture and identity. They believed that the BCC was a place they could learn about and discuss Black issues and current ideas. SELF-PRESERVATION AND MATTERING Students felt that the BCC was a place they could go and feel a sense of comfort and relief. For them, they could speak freely and not feel treated as strange at the Black culture center compared to the larger campus. Black Culture Centers are able to accomplish these outcomes through a range of services, including: Pre College Programs

OPPOSITION AND MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT BCCs Many BCCs face misconceptions. The more prominent of them are that they foster separatism, are only for Black students, and that they are only social (Patton, 2006). However, these misconceptions are based on a lack of understanding of BCCs. BCCs allow students to engage their institutions in ways that they are comfortable with, without having to check their cultures at the door. BCCs are for all students on campus who are interested in learning about Black cultures and themselves in relation to Black cultures. Lastly, as illustrated above BCCs offer a great deal of services beyond social ones, including skill building, academic services, and career/graduate school preparation. BCCs also face funding cuts and attempts to convert into multicultural centers. These options are based on under-valuing the role that ethnic specific centers play and lack of investment in what it takes to achieve educational equity. THE FUTURE OF BCCs According to Cooper (2014) BCCs are intent on becoming more academic in focus (2014), engaging in academic services, relationships with academic programs, housing libraries, and computer labs. The National Association for Black Culture Centers is also implementing an accreditation process for effectiveness in Black Culture Centers (see Appendix A) to aid in the process. According to Cooper (2014) “Yale's center is working with the archivist of the campus library to preserve artifacts, pictures and memorabilia, and provide electronic access to those materials” (p.7). Some BCCs are becoming involved in tracking and monitoring recruitment and retention rates and experiences at their institutions (Walker, 2007). There is also a recent push to collect hard data on the impact of their centers on students, given the general lack of data. WORKS CITED Cooper, K. J. (2014). Black culture centers are embracing multiculturalism and intellectual conversation. Diverse: Issues In Higher Education, 31(15), 6-9. Patton, L. D. (2006). Black culture centers: Still central to student learning. About Campus, 11(2), 2-8. Walker, M. A. (2007). The evolution of Black culture centers. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education, 23(24), 16-17. APPENDIX A: Criteria for Center Accreditation I. Institutional Commitment and Responsibilities A. There should be a direct reporting connection of Center to chief academic or student activities administrator. B. Center should be integral part of institution’s educational and environmental culture.

A. Center must be institutional member of ABCC. B. Center must successfully complete Preliminary Information Form, self-study and peer review processes. Completion of Preliminary Information form and acceptance by the Council. Completion of self-study process and acceptance by the Council. Successful peer-review process of the Council’s visiting team. C. Center must meet minimal standards outlined in the ABCC handbook, including III and IV of this Accreditation Outline. III. Initial Membership A. Center must be institutional member of ABCC. B. Center must successfully complete the ABCC accreditation process. C. Center has probationary membership of one year. D. Center’s institution must demonstrate ability to meet guidelines of institutional commitment and responsibilities. E. Center must demonstrate evidence of meeting conditions of eligibility. IV. Center’s Missions and Purpose A. Center should demonstrate clear evidence of meeting the following related missions identified in the ABCC Constitution:

A. Center must demonstrate effectiveness in the following areas:

A. Qualifications of Director(s) and other professional staff, must be met.

“Thug” is the New “Brute”: The Posthumous Demonization of Black Males Killed by Law Enforcement5/1/2016 Written by Serie McDougal

It must be understood, as Christopher Booker (2000) explains, that Black male existence was criminalized in the early stages of the American colonial experience; starting with physical movement. Freedom of movement throughout towns during slavery was associated with the male gender role. Among the enslaved, Black males were the more likely to leave their plantations than females due to their greater likelihood of being hired out to work by their masters. To police them, slave holding states enacted laws, like South Carolina’s Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves. Such laws required that slaves who were off their plantations to carry a pass or ticket permitting their movement in public spaces. Otherwise, they would be subject to whipping, torture, and mutilation. In early colonial America, serving on policing units called slave patrols, was considered an obligation for 18—45-year-old White males. Ultimately, in most places, these units were replaced by formalized police forces (Booker, 2000). Black males continue to struggle with freedom of movement. This historical context is fundamental to understanding present day patterns of police interaction with Black males. What’s more, abuse of Black males had to be justified so that policing forces could allay their occasional concerns about the impropriety of their actions. In the past, treatment of Black men was rationalized by stereotypes about them that emerged from the religious and scientific communities who described them, respectively, as scientifically inferior, savage, and spiritually damned. Contemporary society is not far removed from this past, given the social threats Black men continue to face. How are the abuses of Black males rationalized and sanitized today? Smiley and Fakunle’s (2016) have recently published a new and profound investigation into the evolution of language used to describe brutality enacted on Black men during slavery and the contemporary coded racist language used to describe Black men who are killed by law enforcement today. They describe the ways that media reports use language to posthumously demonize and criminalize unarmed Black men killed by police to justify their deaths. They note that during slavery, popular American literature portrayed Black males as docile and submissive. However, after the civil war, Black males represented greater economic and political competition for Whites. This threat caused a shift in White stereotypical portrayals of Black males as submissive to Black males being portrayed as brutish, merciless, savage monsters. Terms like “thug” as they are used in the media today are extensions of former terms like “savage” and “brute” (Smiley & Fakunle, 2016). In their analysis of newspaper articles published after the deaths of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Akai Gurley, Tamir Rice, Tony Robinson, and Freddie Gray, Smiley and Fakunle (2016) found that the media focus on peripheral information about these Black males to justify their deaths. This information includes their behaviors, appearances, locations, and lifestyle. For example, Eric Garner's and Michael Brown’s large physical size and past criminal behaviors were used to present them as perpetrators and non-victims and, by way of this, to justify their murders. New articles oddly emphasized Akai Gurley’s tattoos, hairstyle, and style of dress. News reports also used a disproportionate amount of words to describe the dangerous neighborhoods that Akai Gurley and Freddie Gray were from although this information had nothing to do with the actions involved in their killings. Although it had nothing to do with the officers’ decisions to open fire on a child, news reports drew attention to Tamir Rice’s mother’s criminal background. Smiley and Fakunle (2016) explain how important it is to expose such attempts to invalidate claims of illegality by using language to transform the dead into “thugs.” Moreover, their research raises the importance of Black journalism. Perhaps future academic and journalistic research will look into the political and economic functional value of these portrayals of Black males. After all, social stereotypes of Black males have always had some practical value, maintaining White power and privilege and\or the denial of power and privilege to Blacks. Works Cited Booker, C.B. (2000). “I will wear no chain!” A social history of African American males. Westport, CT: Praeger. Smiley, C. , & Fakunle, D. (2016). From "brute" to "thug: " the demonization and criminalization of unarmed black male victims in america. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26(3-4), 350.  Written by Serie McDougal Malcolm X once compared racist conservatives to wolves who show their teeth and do not try to hide the harm they mean to Black people. But, he also explained how the racist liberal approach was much more like that of the fox. While the wolf shows its teeth and snarls, the fox shows its teeth and pretends to be smiling. The fox, as depicted in most folk tales, is always more deceptive and dangerous because its ill-will remains hidden behind good intentions. The Arizona based conservative attack on Ethnic Studies was very direct in its rejection of the core values of Ethnic Studies, depicting it as a threat to national unity.  The Arizona style approach used to attack Ethnic Studies would not work in San Francisco. Nevertheless, the good intentions of San Francisco State University are embodied in the values of its mission statement, which touts a commitment to diversity, social justice, and community. The College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University is founded on several principles including:

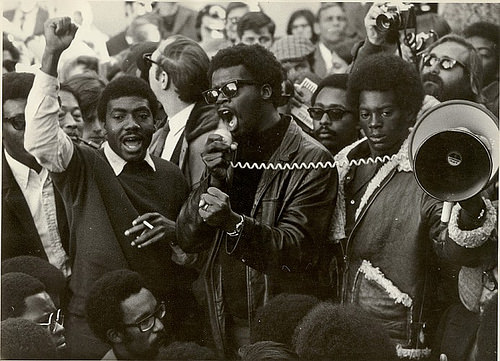

Evidence based research demonstrates the positive effects that Ethnic Studies curriculum has on student academic achievement, student engagement, graduation rates, and self-efficacy. Under the auspices of “a new budgetary discipline”, the current proposal to significantly cut the budget of the College of Ethnic Studies is a reflection of the value that the university leadership currently places on diversity, social justice, and community. The university is claiming that the college spends too much in its efforts to serve underserved students. Not at all ironically, as the budget allocation for the College of Ethnic Studies is diminished, the University is currently planning to resource its growing athletic program. The proposed cuts would result in a 40% loss of Ethnic Studies courses, making it difficult for students to take the courses they would need to graduate. This would also impact our departments’ ability to offer viable degree granting programs. These courses also play a big role in diversifying the university’s curriculum. Ethnic Studies lecturers would lose their positions, meaning the college would lose 50% of its teachers. The Cesar Chavez Institute, which is dedicated to research and community empowerment, would be shut down. The graduate program would no longer be able to offer courses or have a coordinator. The Ethnic Studies Resource and Empowerment Center which advises students on their career goals, academic goals, and funding opportunities would also be shut down. Ethnic Studies work-study student positions would be eliminated. Lastly, professors would get no release time or sabbaticals. While the approach taken in Arizona was to institute a ban on Ethnic Studies, the budget proposal of the president and provost at San Francisco State is fashioned to economically bleed the one and only College of Ethnic Studies to the point that it can no longer function. As Malcolm X urged us to remember, the fox and the wolf come from the same family of canines, just as attacks on Ethnic Studies come in many forms but are fixed on the same objective. They are a part of the same racist conservative political agenda to roll-back the democratization of higher education that students fought for in the 1960s. The true fear of Africana Studies or any of the Ethnic Studies departments, is not their celebration of diversity, it’s the fact that they equip students with the intellectual and academic resources and consciousness to go out into the world, challenge oppression, inequity, and shift the balance of power. With that said, the President of the University’s office has a fundamental misunderstanding of the climate of the times that we currently live in. This would be the time to help them understand that the College of Ethnic Studies will settle for no less than an increase in funding for its work. Without the College of Ethnic Studies, the university’s fund raisers could not move about the state and country bragging about the unique diversity of its campus. With less money, the College of Ethnic Studies’ students, faculty, programs, and institutions have done a disproportionate share of the work of serving underserved populations because it’s what we love to do. When you hear the president make a claim about how diverse the campus is in public from now on, he should be met with a resounding chorus of “40%!!!”, because that’s how many Ethnic Studies courses would have to be cut to balance the budget he has proposed. Our students, faculty and supporters are ready to battle with whatever may come, wolves or foxes alike. Anyone can send a letter advocating on behalf of the college to: President Leslie Wong: ADM 562 – (415) 338-1381 – [email protected] Provost Sue Rosser: ADM 455 – (415) 338-1141 – [email protected] Written by Serie McDougal In the U.S., it is no secret that deaths due to gun violence is a problem that disproportionately affects African Americans. This is a key, yet often unspoken, factor in the recent debates over the republican decision to include a ban against funding for gun-violence research in spite of continued shootings. But this conversation must be placed into historical context, recent history, and remote history. Current discussions of the under-valuing of Black life rightly inspire discontent. But sometimes, they inspire surprise and astonishment because they are rooted in a mystical version of American history. A staple of American media, but also its life and history, has been and continues to be the normalized spectacle of violence enacted on Black people. From the earliest normalized images of public whippings, burnings, beatings, and mutilations to current media images coupling Black people and acts of violence, legal and extra-legal police violence, and gun violence. The congressional debate over republican refusal to remove the ban against gun violence research hinges in part on who’s dying, who’s most affected, and who cares. While some congress members may be isolated from the effects of gun violence, we know that it is often fatal, it damages physical and mental health, families and relationships, and neighborhoods (Felson & Painter-Davis, 2012). Congress stripped funding from the Centers of Disease Control (CDC) and the National Institute of Health (NIH) in the mid 1990’s. The ban is now 17 years old. Under pressure from gun lobbyists, congress stripped $2.6 million dollars (the exact amount that the agency had been spending on violence research) from the CDC’s budget and also stipulated that none of their funding “may be used to advocate or promote gun control”. The reasons for this ban can be traced back to a 1993 article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, by Arthur Kellerman and Colleagues called Gun Ownership as a Risk Factor for Homicide in the Home. The article demonstrated a strong independent relationship between the possession of a gun in the home and increased risk of homicide. The National Rifle Association (NRA) responded to the report by campaigning to eliminate the CDC’s National Center for Injury and Prevention. Although the center remained, congress included language in the 1996 Omnibus Consolidation Appropriations Bill, known as the Dickey Amendment (named after Representative Jay Dickey), stating that "None of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control." Congress also took $2.6 million dollars away from the CDC’s budget, the exact amount that it had previously in firearm injury research. It is important to note that congress has not attempted to deter research tied to advocacy in the areas of HIV\AIDS, Motor-Vehicle Injuries, Cancer, and Smoking. However, evidence tied to intervention and prevention policy is seen as a threat as it related to gun ownership. The American Psychological Association along with hundreds of other scientists have called for the lifting of the ban. It is important to note that research is not absolutely prohibited in the sense that there is still research being done using available administrative medical data. However, depending on available medical data means that research validity will be limited. Relying on available data from hospital administrative records means that researchers cannot measure what they want to directly because they are using data collected for different purposes. In 2013, President Obama, in response to the death of the mostly white victims of the mass shooting at Sandy Hook elementary school, advocated for the CDC to be funded to do more research to study the root causes of gun violence. However, the appropriations were blocked and the language banning research remained. Today the ban continues in spite of the fact that the original author of the ban (amendment) has publicly expressed his support for gun violence research and his regret for the role he played in blocking such research. The rider ensures that congress is not duty-bound to act on the results of government sponsored research into the root causes of gun violence and prevention strategies. Given our knowledge of the value for Black life in the American context and the poor outcomes of appeals to the sympathetic ears of others, there must be a different kind of advocacy in addition to compelling funding and research from congress and the CDC. Afrocentric organizations such as the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi) has been investigating the root causes of gun violence for years in addition to informing evidence based interventions to reduce gun violence in the Black community specifically such as the Aban Aya Youth Project. Programs like this have been demonstrated to be effective, they are culturally grounded and able to significantly reduce violent behavior, provoking behavior, school delinquency, drug use, and other kinds of risk behavior beyond removing guns from home. The recent ban on funds on gun violence should reinvigorate the congressional Black caucus to fund its own research on advocacy oriented research on Black youth and gun violence given that they are the most vulnerable to violence. Works Cited Felson, R. and Painter-Davis, N. (2012). Another cost of being a young Black male: Race, weaponry, and the lethal outcomes in assaults. Social Science Research, 41(5), 1241-53. Written by Serie McDougal and Sureshi Jayawardene REVOLUTIONARY CONTAGION ACROSS CAMPUSES During slavery in 1851, Louisiana physician, Dr. Samuel Cartwright explained that some enslaved African people were suffering from a disease called drapetomania, which caused them to want to run away from white captivity (Cartwright, 1851). He explained that there were a preliminary set of symptoms of this illness and he called it incipient drapetomania. It included expressions of dissatisfaction with and resistance to White dominance. According to Cartwright (1851), slave owners needed to be aware of this pathology so they could stop it from spreading by administering the appropriate treatment, whipping. Today, a different contagion of self-determination is spreading across campuses in the U.S. Students at the University of Missouri have realized their power and are effectively using it to transform the racist climate at their school. This has spurred Black student-led political action on numerous campuses across the country. And like the White supremacists of the 1800s, conservatives, including presidential candidate Donald Trump, have attempted to pathologize them by calling their resistance to oppression “crazy.” Just last Friday, a conservative media source summarized some of these student demands as “nutty” and “disturbing,” while acknowledging that many of them are “reasonable things for black and minority students to be concerned about." AWAKENING THE GIANT Overrepresented in college athletics, African American students face stereotypes that cast doubt on their interests outside of sports on campuses (Bonner, 2014). In the fullness of time, the United States is only a few hundred years removed from forced displays of physicality such as slavers who forced enslaved Africans to engage in athletic competition with other enslaved Africans as a form of entertainment for whites (Roden, 2006). African people have used sports as a form of self-expression and physicality, a career path, a means of learning team work and discipline, a means of healthy competition and physical conditioning, and to pay for college education. However, abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote, as early as the 1800s, that Whites used sports to politically pacify Blacks and to prevent rebellion (Douglass and Garrison, 1846). Whites expected then, as many do today, that Black athletes be grateful entertainers who remain politically silent and submissive. The Back football players at Missouri acted in the revolutionary tradition of Black athletes such as Paul Robeson, Jim Brown, and Muhamad Ali who stood on the principles of self-determination, justice, Black community, and liberation. EVOKING THE BLACK CAMPUS MOVEMENT Further, the ongoing Black student protests on college campuses nationwide and subsequent demands to university administrators reflect the fervor of Black student protests during the Black Campus Movement of the 1960s. At that time, Black students called for similar shifts and commitments, in what Ibram Kendi (formerly Rogers) terms the “racial reconstitution of higher education” in America. Scholars have documented the Black Campus Movement in the 1960s and their highly generative outcomes such as a number of Black Studies departments and graduate programs which many of us are privileged to be housed in. Because of these achievements, Black students are exposed to more culturally relevant curricula as well as learning environments that require careful thought and research that can improve Black communities. But, if these gains were made, what accounts for Black student protests today? Their demands, too, are similar to those made in the late 1960s. Central to these demands at approximately 37 colleges and universities in the past few weeks are issues of racism and White supremacy amidst other isms and phobias. In a recent blog post for H-Afro-Am, an Africana Studies network of scholars, Kendi wrote, “Despite th[e] recent burst in books on the subject, we still have merely scratched the surfaced on this massive Black campus movement. We have yet to detail what happened on the vast majority of the more than 500 campuses in 49 states that Black student activists rocked towards diversifying from 1965 to 1972. Even at Mizzou, there is no major history on the BCM. The story of those amazing Legions of Black Collegians, founded in 1968, has yet to be told.” Additionally, we need to carefully examine the go-to rhetoric of diversity and inclusion that universities tout as a quick response intended to quell student unrest. We need to parse out the symbolic gestures from real efforts that actually meet student demands. Amer Ahmed recently penned, “these same institutions maintain their rhetoric about diversity and inclusion in superficial ways attempting to do little as possible without truly having to change.”  #RhodesMustFall Photo source: thedailyvox.co.za #RhodesMustFall Photo source: thedailyvox.co.za THE GLOBAL BEAST: WHITE SUPREMACY For Black students confronted with the effects of everyday forms of racism as well as more structural racist impediments to their wellbeing and learning, universities are proving to be a site of contestation beyond the United States. In early October this year, a crowd of 2,000 Black students at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa shut down the university just prior to the start of exams. The campus has remained closed since. They protested the cost of higher education for poor Black students who are struggling to remain enrolled in the university, as well as the university’s and government’s inadequate efforts to ameliorate these costs. In the spring, Black students at the University of Cape Town demonstrated to have the bronze statue of British colonial administrator, Cecil Rhodes, removed from its central position on campus. Their determined efforts led to international attention through a social media campaign tagged #RhodesMustFall. Students stressed that the statute was not merely something that caused discomfort, but the ultimate symbol of institutionalized racism at the university. They demanded the Executive Council—the highest authoritative body at the university—remove the problematic Rhodes figure, but also take seriously the deeply entrenched racist values and norms. This was soon followed by #FeesMustFall, and the students won their demand of a 0% increase in tuition fees. In September, Black students at the University of Nairobi protested against delayed Higher Education Loans Board (HELB) loans which prevented their continued enrollment. Similar to demands for transformative change at US institutions of higher education, students on the African continent are also seeking “decolonization,” “transformation,” and ultimately a “racial reconstitution” for improved and culturally sensitive learning environments and opportunities. Certainly, the declared solidarity between #RhodesMustFall, #BlackLivesMatter, #ConcernedStudent1950, and similar campaigns that lend themselves to themes of diasporic spirit and Pan African politics. What we are also witnessing in an unprecedented way is the degree to which the roots and severity of institutional assaults on Black life and learning are plaguing the African world. Works Cited Bonner, F.(Ed.) (2014). Building on resilience. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publications. Cartwright, S.A. (1851). Report on the diseases and physical peculiarities of the Negro race. The New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal, May, pp. 691–715. Douglass, F., & Garrison, W. L. (1846). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass: An American slave. Wortley, near Leeds: Printed by J. Barker. Roden, W. (2006). Forty million dollar slaves. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. Rogers, I. (2012). The Black campus movement: Black students and the racial reconstitution of higher education, 1965-1972. New York: Palgrave. Written by Sureshi Jayawardene October is breast cancer awareness month. During this time awareness campaigns advocate nationally for early testing and diagnosis. The American Cancer Society (ACS) has been key in these efforts and, in the past, has taken an aggressive approach to screening, recommending that women age 40 and older have mammograms and clinical exams annually. However, on October 20th 2015, the organization issued new guidelines for mammograms. They said that women should begin mammograms later and have them less frequently. According to their announcement, the ACS recommends women with an average risk of breast cancer start having mammograms at age 45 and continue annually until 54. Following this, they recommend screenings every other year so long as women remain healthy. In addition, the organization states that women who have experienced no symptoms or breast abnormalities need no longer have clinical breast exams. A clinical breast exam is when a nurse or doctor feels for lumps. The ACS also notes that mammograms are less useful for younger women and inconsistencies such as false positive results can unnecessarily lead to additional testing including biopsies.

BLACK WOMEN AND BREAST CANCER These guidelines have been met with some disagreement from organizations especially concerned with minority communities. For instance, the Mayo Clinic indicates that breast cancer affects Black women at a younger age than other groups and that tumors can be significantly more aggressive. African American women are also less likely to take action early enough. Linda Goler Blount, president and CEO of Black Women’s Health Imperative highlights the role of health insurance in this situation. According to her, African American women are 45% less likely to have health insurance than White women and have a 40% greater mortality rate as a result of breast cancer. In their recent study, Keenan et al (2015) state that these racial disparities in tumor outcomes between White and Black women might be explained by more aggressive tumor biology in Black women. Each year, approximately 6,000 Black women die from breast cancer. If the mortality rate for Black women equaled that of White women, these deaths would be reduced by 2,400. The ACS should take into consideration the racial disparities of breast cancer so that early detection and other treatment mechanisms can be made available for Black women. If African American women are able to have early detection of their cancer – which is the period when they are most successfully treated and women can receive quality treatment – fewer women would die. CULTURE AND BREAST CANCER PREVENTION Health professionals and researchers need to look at cultural factors as an initial step toward addressing the failures of breast cancer prevention and control strategies (Guidry et al., 2003). While ethnic and ancestral factors may differ among women of African descent, “there remains a set of shared beliefs, values, and experiences that researchers should understand when evaluating the importance of culture in breast cancer prevention and control” (Guidry et al., 2003, p. 319). To this end, such programs need to be consistent with cultural components in the Black community. Some of these include attitudes toward kinship bonds, flexible family roles, religiosity, education, and work (Guirdy et al., 2003). Community-based interventions can be effective in connecting Black communities to health agencies. These often work to establish social networks, serve as a resource, and offer social support (Guidry et al., 2003). Some of the most noteworthy community-based initiatives include Save Our Sisters Project, the North Carolina Breast Cancer Screening Program, and the Witness Project. Not only have these programs been sensitive to the culturally specific needs of their Black women patients, but have positively influenced breast cancer screening behavior among their target population (Guidry et al., 2003). Thus, attending to the cultural and psychosocial factors in through community health services can yield positive outcomes for Black women in terms of breast cancer awareness, treatment, and support. WHAT CAN BLACK WOMEN DO NOW? Given the new ACS guidelines and the additional health related burdens faced by Black women socially and economically, learning about risks for breast cancer are crucial. For Black women under 40, seeking your physician’s advice about your particular risk factors can be beneficial as well as finding out whether a base line mammogram is necessary. For women over 40, making a mammogram an annual occurrence is important. Under the Affordable Care Act, mammograms are a covered benefit with no cost to the patient. In addition, learning about local and regional community health initiatives and other resources can also prove helpful. BREAST CANCER RESOURCES FOR BLACK WOMEN

Works Cited Guidry, J.J., Matthews-Juarez, P., and Copeland, V.A. (2003). Barriers to breast cancer control for African-American women: The interdependence of culture and psychosocial issues. Cancer 97 (1 supplemental): 318-23. Keenan, T., Moy, B., Mroz, E.A., Ross, K., Niemierko, A., Rocco, J.W., Isakoff, S., Ellisen, L.W., and Bardia, A. (2015). Comparison of the genomic landscape between primary breast cancer in African American versus White women and the association of racial differences with tumor recurrence. Journal of Clinical Oncology. DOI 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.2126 Written by Serie McDougal “We've got to strengthen black institutions. I call upon you to take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit your money in Tri-State Bank. We want a "bank-in" movement in Memphis. Go by the savings and loan association. I'm not asking you something that we don't do ourselves at SCLC. Judge Hooks and others will tell you that we have an account here in the savings and loan association from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. We are telling you to follow what we are doing. Put your money there. You have six or seven black insurance companies here in the city of Memphis. Take out your insurance there. We want to have an "insurance-in.” - Been to the Mountain Top, Martin Luther King, Jr On April 3, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his final speech. One of the last messages he delivered that night was on the dual benefit of Black economic solidarity. He said, “Now these are some practical things that we can do. We begin the process of building a greater economic base.

And at the same time, we are putting pressure where it really hurts”. Dr. King implored the Black community to spend our money with Black institutions to create a strong base that would allow us to meet many of our own needs. Moreover, King believed that this cooperation would also place economic sanctions on racist institutions for unmet demands for justice and their on-going racial discrimination. Some prefer to remember King’s call for reconciliation more than his demands for justice. However, this dying message from our dear ancestor couldn’t be more relevant than it is today. STRIKING RACIST INSTITUTIONS Black-owned businesses are essential to Black community empowerment because evidence shows that they generate wealth, and create investment opportunities and employment prospects for Black people (Conrad, Whitehead, Mason, & Stewart, 2005). In addition, U.S. consumer spending in the months of November, December, and January are crucial to many of the largest companies in the United States. Racist large corporations such as Wal-Mart Stores, Abercrombie & Fitch and General Electric, Wells Fargo and many others have also made people of African descent in the U.S. victims of hiring discrimination, lending discrimination, wage discrimination, and other offenses while continuing to benefit from the Black community’s $1 Trillion buying power. Given the significance of U.S. consumer spending, this makes the next three months, the perfect time to, in the words of Martin Luther King, “redistribute the pain” that the Black community has felt as a consequence of racial injustice. MAGGIE'S LIST: MOVING BEYOND THE FORCED-INTO-UNITY THESIS The forced-into-unity thesis is the belief that Black community empowerment can only come as a result of segregation and oppression. While it is true that many Black businesses grew and developed during the time of de jure segregation, many survived and thrived thereafter, despite the increased competition for Black consumer dollars that Black businesses faced when segregation ended. Today, Black businesses continue to suffer from being undercapitalized, conservative tax policies, and a lack of diversity and managerial training. An economic solidarity charge must be tempered by the warning that pure Black capitalism could simply exacerbate class divisions within the Black community if it is not grounded in the philosophy of collective Black liberation. However, the Black community can change this and more by using its trillion dollar buying power attached to the political agenda of Black collective advancement. But how? Quite timely, sister Maggie Anderson is launching her national list of Black businesses, and a smartphone app starting on November 1st, 2015. There are a great number of lists of Black owned businesses available electronically and at local Black chambers of commerce; however, Anderson’s is among the newest. Anderson is the author of the critically acclaimed book, “Our Black Year,” about how her family spent a whole year buying all goods and services from Black businesses. Since her family’s experiment, Anderson has dedicated her life to Black economic solidarity. Spending is not just about money because spending power is related and leads to political power. But power will only come when Black spending power is linked to Black political priorities. Works Cited Conrad, C.A., Whitehead, J., Mason, P. & Stewart, J. (2005). African Americans in the U.S. economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed