|

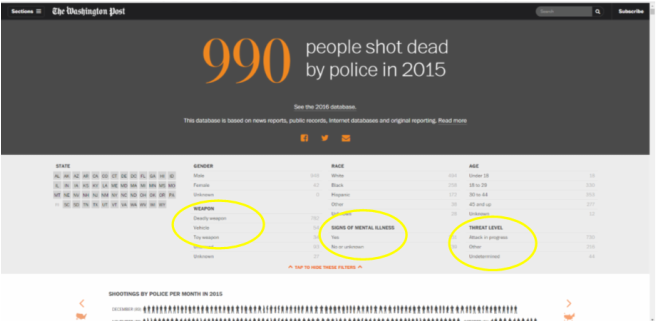

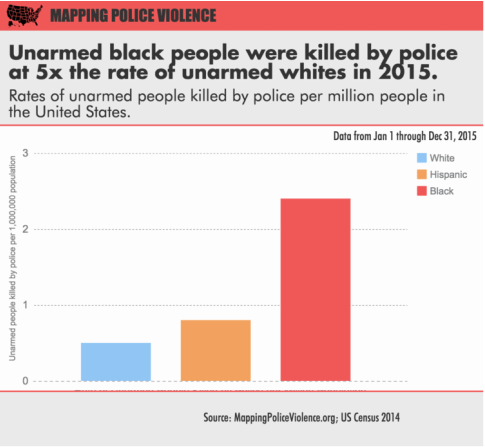

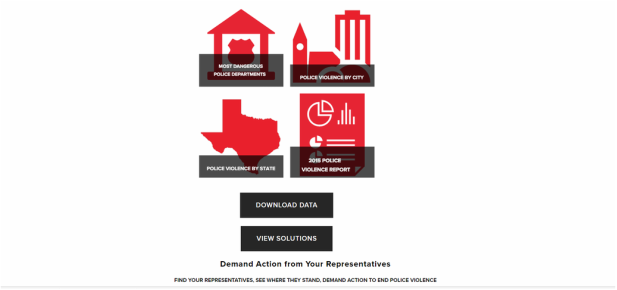

Written by Sureshi Jayawardene Ida B. Wells once said, “those who commit the crimes write the reports.” Today, the glaring truth of Wells’ words reverberate throughout the Black community as the death toll steadily rises, while law enforcement officers face minimal charges often going without a conviction, and the criminal justice system remains the same well-oiled machine. As the Afrometrics article, “The False Premise of ‘Not Working’” from April 2015 pointed out, the system is working. In fact, it’s working rather well. In the late 19th century, Wells was concerned about the powers that would narrate and subsequently find ways to justify the extrajudicial killings of Black people. She dedicated her life to bringing attention to the dominant discourse, hegemony and American spirit underlining these killings. An avid activist and Black political theorist, Ida B. Well’s words are so relevant today, not simply because of the ceaseless gratuitous violence against Black people, but also because of how documentation of such violence is taking place. Or, not taking place. It is quite ironic, but not writing reports is as good as writing a report that does everything to avoid incriminating the murderer. The Reports They Don’t Write In October 2015, at a US Justice Department summit on violent crime reduction FBI director James Comey stated, “It is unacceptable that the Washington Post and the Guardian newspaper from the UK are becoming the lead source of information about violent encounters between [US] police and civilians. That is not good for anybody.” Comey claimed it was “embarrassing and ridiculous” that entities independent of the federal government had been more efficient in this data collection and that they made it easily accessible to everyone. However, a year prior to that, a few days before Michael Brown’s violent death, the most reputed crime-data experts in DC determined they could not accurately count how many Americans die each year at the hands of police, so, they put an end to counting altogether. Data Compilation Since we are the victim and we fight daily to avenge those who are killed, we have to be the ones to compile the evidence and put together the reports. We have to compose our own narrative so that it will ultimately aid us in our collective action to bring down the forces that oppress us. Today, the FBI claims to know little more than a year ago when Comey made his embarrassing admission. But, there is plenty data, as Kia Makarechi, story editor and associate director of audience development at Vanity Fair, reported in July this year. He writes, “eighteen academic studies, legal rulings, and media investigations shed light on the issue roiling America.” The Guardian, through a crowdsourced project, The Counted, has created an extensive searchable database of police killings in the US. Here you will find amassed significant detail about each police involved death of a civilian from 2015. For each case, you can also find links to news and media coverage of the incident: This database also has a “send a tip” tab encouraging vigilance and awareness among citizens to report any helpful information regarding these incidents. In a separate effort, the Washington Post tracked the number of people killed by the police in just the year 2015. The data gathered includes demographic information for each victim and also notes conditions such as “signs of mental illness,” “threat level," and "weapon.” According to Mapping Police Violence, in 2015 alone, unarmed Black people were killed by police at 5 times the rate of unarmed White people. This organization presents data in easy-to-digest infographic form. Readers can find a map of police violence across the nation, images that portray the rate of conviction of police officers for their crimes, the “most dangerous police departments,” police violence by city and state, as well as annual reports. The organization also urges visitors to the website to demand political action. Other databases also exist. They include: Fatal Encounters and the Facebook compilation Killed By Police. Finally, a database specifically focused on African American deaths at the hands of law enforcement, Operation Ghetto Storm, which is supported by the Malcolm X Grassroots Committee issued a report in 2014. This was actually an updated version of their 2012 report which details their organizational mission and objectives, and tallies the number and frequency of extrajudicial killings of Black people. The author, Arlene Eisen, links present day violence against Black communities to the long history of oppression and subjugation endured by African Americans. Furthermore, Eisen underscores that the model of protest immediately after a police shooting is insufficient to take down the system that sustains this oppression. She describes necessary steps to act against the continued war on Black people, including self-defense training and organization in the Black community, but also building broad alliances with other oppressed groups to work together against the continuing modes of violence on our communities.

In addition, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled last week in the gun conviction case of Jimmy Warren that the fact that Warren ran away should not be used to further incriminate him. The court said that according to state law, individuals had the right to not speak to police and even walk away from them if they were not being charged with anything. The justices further declared, “…flight is not necessarily probative of a suspect’s state of mind or consciousness of guilt. Rather, the finding that black males in Boston are disproportionately and repeatedly targeted for FIO [Field Interrogation and Observation] encounters suggests a reason for flight totally unrelated to consciousness of guilt. Such an individual, when approached by the police, might just as easily be motivated by the desire to avoid the recurring indignity of being racially profiled as by the desire to hide criminal activity. Given this reality for black males in the city of Boston, a judge should, in appropriate cases, consider the report’s findings in weighing flight as a factor in the reasonable suspicion calculus” The court cited evidence from a 2014 ACLU of Massachusetts report about the disproportionate levels of police stops experienced by Black people. The court also cited evidence from Boston police data on field interrogation and observation (FIO) to further support this. Our Own Vigilance and Racial Protectionism As a parent of a Black son, I often find myself frustrated and helpless that as his mother any amount of protection I afford my son will not safeguard him from experiencing racist violence. As we have seen in recent years, Black people are being killed by police for simply being. A new study from the Yale Child Study Center found that ‘implicit bias’ affects how teachers treat African American males from as young an age as 4 years old. Implicit bias refers to unconscious prejudices and stereotypes that influence interaction with different people. The researchers examined “the potential role of preschool educators’ implicit biases as a viable partial explanation behind disparities in preschool expulsion.” Researchers found that when expecting challenging behaviors, educators looked longer at Black children, particularly Black boys. The findings also suggest difference in implicit biases based on teacher race. The findings of this study demonstrate the deep-seated nature of racist thinking and ideas. It is clear that teachers’ hyper-vigilant gaze at Black boys is influenced by the dominant culture’s racist narrative of Black criminality. However, to call something implicit and unconscious is dangerous, because this suggests that people have little to no control over the “unconscious” and that everyone is “biased” and “prejudiced” to some varying degree. In turn, there is little that comes in the form of a critique of the overarching dominant culture that sustains the real culprit: racism. While the term implicit bias can be problematic because it deflects accountability and transparency for racism and its consequences, the results of this study are useful for Black parents making decisions about their children’s education, everyday racial socialization, and overall safety from racial violence throughout the lifespan. Taking action regarding the impact of racial profiling and presumptions of criminality at the preschool age might aid Black parents and larger community networks in preventing our loved ones from being featured in the above databases.

0 Comments

“Thug” is the New “Brute”: The Posthumous Demonization of Black Males Killed by Law Enforcement5/1/2016 Written by Serie McDougal

It must be understood, as Christopher Booker (2000) explains, that Black male existence was criminalized in the early stages of the American colonial experience; starting with physical movement. Freedom of movement throughout towns during slavery was associated with the male gender role. Among the enslaved, Black males were the more likely to leave their plantations than females due to their greater likelihood of being hired out to work by their masters. To police them, slave holding states enacted laws, like South Carolina’s Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves. Such laws required that slaves who were off their plantations to carry a pass or ticket permitting their movement in public spaces. Otherwise, they would be subject to whipping, torture, and mutilation. In early colonial America, serving on policing units called slave patrols, was considered an obligation for 18—45-year-old White males. Ultimately, in most places, these units were replaced by formalized police forces (Booker, 2000). Black males continue to struggle with freedom of movement. This historical context is fundamental to understanding present day patterns of police interaction with Black males. What’s more, abuse of Black males had to be justified so that policing forces could allay their occasional concerns about the impropriety of their actions. In the past, treatment of Black men was rationalized by stereotypes about them that emerged from the religious and scientific communities who described them, respectively, as scientifically inferior, savage, and spiritually damned. Contemporary society is not far removed from this past, given the social threats Black men continue to face. How are the abuses of Black males rationalized and sanitized today? Smiley and Fakunle’s (2016) have recently published a new and profound investigation into the evolution of language used to describe brutality enacted on Black men during slavery and the contemporary coded racist language used to describe Black men who are killed by law enforcement today. They describe the ways that media reports use language to posthumously demonize and criminalize unarmed Black men killed by police to justify their deaths. They note that during slavery, popular American literature portrayed Black males as docile and submissive. However, after the civil war, Black males represented greater economic and political competition for Whites. This threat caused a shift in White stereotypical portrayals of Black males as submissive to Black males being portrayed as brutish, merciless, savage monsters. Terms like “thug” as they are used in the media today are extensions of former terms like “savage” and “brute” (Smiley & Fakunle, 2016). In their analysis of newspaper articles published after the deaths of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Akai Gurley, Tamir Rice, Tony Robinson, and Freddie Gray, Smiley and Fakunle (2016) found that the media focus on peripheral information about these Black males to justify their deaths. This information includes their behaviors, appearances, locations, and lifestyle. For example, Eric Garner's and Michael Brown’s large physical size and past criminal behaviors were used to present them as perpetrators and non-victims and, by way of this, to justify their murders. New articles oddly emphasized Akai Gurley’s tattoos, hairstyle, and style of dress. News reports also used a disproportionate amount of words to describe the dangerous neighborhoods that Akai Gurley and Freddie Gray were from although this information had nothing to do with the actions involved in their killings. Although it had nothing to do with the officers’ decisions to open fire on a child, news reports drew attention to Tamir Rice’s mother’s criminal background. Smiley and Fakunle (2016) explain how important it is to expose such attempts to invalidate claims of illegality by using language to transform the dead into “thugs.” Moreover, their research raises the importance of Black journalism. Perhaps future academic and journalistic research will look into the political and economic functional value of these portrayals of Black males. After all, social stereotypes of Black males have always had some practical value, maintaining White power and privilege and\or the denial of power and privilege to Blacks. Works Cited Booker, C.B. (2000). “I will wear no chain!” A social history of African American males. Westport, CT: Praeger. Smiley, C. , & Fakunle, D. (2016). From "brute" to "thug: " the demonization and criminalization of unarmed black male victims in america. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26(3-4), 350. Written by Serie McDougal In the U.S., it is no secret that deaths due to gun violence is a problem that disproportionately affects African Americans. This is a key, yet often unspoken, factor in the recent debates over the republican decision to include a ban against funding for gun-violence research in spite of continued shootings. But this conversation must be placed into historical context, recent history, and remote history. Current discussions of the under-valuing of Black life rightly inspire discontent. But sometimes, they inspire surprise and astonishment because they are rooted in a mystical version of American history. A staple of American media, but also its life and history, has been and continues to be the normalized spectacle of violence enacted on Black people. From the earliest normalized images of public whippings, burnings, beatings, and mutilations to current media images coupling Black people and acts of violence, legal and extra-legal police violence, and gun violence. The congressional debate over republican refusal to remove the ban against gun violence research hinges in part on who’s dying, who’s most affected, and who cares. While some congress members may be isolated from the effects of gun violence, we know that it is often fatal, it damages physical and mental health, families and relationships, and neighborhoods (Felson & Painter-Davis, 2012). Congress stripped funding from the Centers of Disease Control (CDC) and the National Institute of Health (NIH) in the mid 1990’s. The ban is now 17 years old. Under pressure from gun lobbyists, congress stripped $2.6 million dollars (the exact amount that the agency had been spending on violence research) from the CDC’s budget and also stipulated that none of their funding “may be used to advocate or promote gun control”. The reasons for this ban can be traced back to a 1993 article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, by Arthur Kellerman and Colleagues called Gun Ownership as a Risk Factor for Homicide in the Home. The article demonstrated a strong independent relationship between the possession of a gun in the home and increased risk of homicide. The National Rifle Association (NRA) responded to the report by campaigning to eliminate the CDC’s National Center for Injury and Prevention. Although the center remained, congress included language in the 1996 Omnibus Consolidation Appropriations Bill, known as the Dickey Amendment (named after Representative Jay Dickey), stating that "None of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control." Congress also took $2.6 million dollars away from the CDC’s budget, the exact amount that it had previously in firearm injury research. It is important to note that congress has not attempted to deter research tied to advocacy in the areas of HIV\AIDS, Motor-Vehicle Injuries, Cancer, and Smoking. However, evidence tied to intervention and prevention policy is seen as a threat as it related to gun ownership. The American Psychological Association along with hundreds of other scientists have called for the lifting of the ban. It is important to note that research is not absolutely prohibited in the sense that there is still research being done using available administrative medical data. However, depending on available medical data means that research validity will be limited. Relying on available data from hospital administrative records means that researchers cannot measure what they want to directly because they are using data collected for different purposes. In 2013, President Obama, in response to the death of the mostly white victims of the mass shooting at Sandy Hook elementary school, advocated for the CDC to be funded to do more research to study the root causes of gun violence. However, the appropriations were blocked and the language banning research remained. Today the ban continues in spite of the fact that the original author of the ban (amendment) has publicly expressed his support for gun violence research and his regret for the role he played in blocking such research. The rider ensures that congress is not duty-bound to act on the results of government sponsored research into the root causes of gun violence and prevention strategies. Given our knowledge of the value for Black life in the American context and the poor outcomes of appeals to the sympathetic ears of others, there must be a different kind of advocacy in addition to compelling funding and research from congress and the CDC. Afrocentric organizations such as the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi) has been investigating the root causes of gun violence for years in addition to informing evidence based interventions to reduce gun violence in the Black community specifically such as the Aban Aya Youth Project. Programs like this have been demonstrated to be effective, they are culturally grounded and able to significantly reduce violent behavior, provoking behavior, school delinquency, drug use, and other kinds of risk behavior beyond removing guns from home. The recent ban on funds on gun violence should reinvigorate the congressional Black caucus to fund its own research on advocacy oriented research on Black youth and gun violence given that they are the most vulnerable to violence. Works Cited Felson, R. and Painter-Davis, N. (2012). Another cost of being a young Black male: Race, weaponry, and the lethal outcomes in assaults. Social Science Research, 41(5), 1241-53. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed