Are Police Obsolete? Part III: White Supremacist Teleology of the Police and Africana People Today4/30/2015 Written by Chris Roberts The White Supremacist Teleology of the Police In his essay The Theoretical and Methodological Crisis of the Africentric Conception Black psychologist W.C. Banks described teleology as a “sense of directedness, of definite ends, of definite purpose” (Banks 1992). Given the historiographical outline of the police in the previous two parts in this series, from its European ideological origins to its contemporary manifestation in the United States, it should be clear that the definite purpose of this entity is indeed to sustain the white ruling elite and its benefactors (the white community writ large) extending the “collective responsibility for maintaining dominance over the Black slaves among them” (Hadden. 2003). In the eyes of the police as an institution, Black people can only exist as slaves because a liberatory Africana humanity, what Modupe describes as “Africana existence on Africana terms” is diametrically opposed to the definite purpose of the police to decimate and dominate Africana people, by any cost and all means. In the 21st century, we find ourselves square within the scope the same white supremacist police entity; it has just adjusted its appearance. The definite purpose of the police profession, from its inception to today, is inexhaustibly clear. It is as Malcolm X said, “racism is like a Cadillac, they bring out a new model every year.” The current model can be found in police departments such as, but not exclusive to, Cleveland, Oakland, Chicago, New York, and Ferguson. Though those are the ones listed, it is important that we understand, as Malcolm X also said, “everything under Canada is the South” so these new models of racism via policing are not the exceptions of the U.S., but they are the norm. If the teleology of our oppressors police force is “the continuation of white supremacy for the purpose of situating Black/Africana/African people as a criminal denomination of sub-humanity in need of eternal punishment and surveillance” then what is our teleology as Africana people? What is our sense of directedness as it relates to tackling this deadly threat. It is my offering to, what I hope is a very robust and critical discourse on this topic, that our sense of directedness be towards self-protection for the purpose of intra communal strategizing and healing. Self Protection: Much of the Black public wanted to believe that the election of Barack Obama in 2008 was going to mark an end to racism in the United States and the dawn of a new era of racial equality and harmony. Many in our ranks hoped that the State would no longer be against Black people but for all U.S. citizenry, of which Black people would be more ingrained than ever before. There was similar fervor in the country during the 1960s with the Civil Rights Act and the alleged desegregation of public schools, the idea was again, that racial harmony was just over the horizon via non-violence and faith in the political process. However, the Black youth of the 60s came to a sobering realization, that the horizon they yearned for was not coming, and that realization, as Dr. Akinyele Umoja tells us in his book We Will Shoot Back “The failure of the national Democratic Party leadership to seat the multiracial delegates of the MFPD and to support the MFPD’s challenge to the legitimacy of segregationist Mississippi Democrats… [and] After all the bombings, deaths, and other forms of terrorism endured by Mississippi Blacks and the Black Freedom Struggle… many activists lost faith in cooperation with White liberals and the democratic party as a means to secure the goals of the struggle” (Umoja. 2013). I contend that the Africana youth of 2015 find themselves at a similar crossroads. The Department of Justice has proven itself unwilling or unable to prosecute to the fullest extent of the law the murderers of Black people. The international human rights organization Amnesty has proven itself unwilling or unable to address the critiques of racial subjugation levied by Black activists within, and external to its organization. The luster off the Obama election gone, and the blood of countless Black people killed by the State still fresh, I contend the Africana youth of today are headed to the same conclusion of the 1960s youth in that “the Movement and Black people in general would have to rely upon themselves and their own resources for their own protection” (Umoja. 2013). Therefore, self-protection is understood as an assessment of the practical ways in which the tactic of armed self-defense which Umoja defines as “the protection of life, persons, and property from aggressive assault through the application of force necessary to thwart or neutralize attack” (Umoja. 2013). The reason I advocate for armed self-defense as self-protection is because it will start us on the path of riding ourselves of the fear we have of the police profession. “Ultimately, the Black Freedom Struggle in Mississippi and the South was a fight to overcome fear. Blacks overcame fear and asserted their humanity…armed resistance played [a role] in overcoming fear and intimidation and engendering Black political, economic, and social liberation. Intra Communal Strategizing: Intra communal strategizing as a point is imperative because the teleology of the intra communal members will be different than that of the external communal members. This is highlighted in the work of Grandpre and Love in the text The Black Book: Reflections from the Baltimore Grassroots warns of the non-profit industrial complex. I value their critique of that, especially given that in many “coalition” meetings around issues of mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex, non-profits. Love states “Those of us on the front line of the fight are not seen as worthy negotiators on these issues that directly affect us. This fundamental contradiction explains the way in which white supremacy informs the inability of people to see Black people as having the collective wherewithal to manage and operate large institutions. Until this mythology is dispelled we will be subject to white control…” (Love, 167). The first point here is that Africana people must discuss the intentional creation of space and place in a way that is not stifling but empowering to Africana people. Secondly, it is indeed from the intentional creation of space that the third point can be addressed. The reason I advocate for intra-communal strategizing is because if our goals are averse to the reason of existence held by the police profession, then. Healing: University of Indiana Bloomington scholar Maria Abegunde says of healing in "Sankofa in Action: Creating A Plan that Works," “Although many approaches in the literature on healing, ritual are holistic... they tend to focus on what I believe are symptoms (violence and the result of violence) as opposed to the cause(s) of the wound. I am suggesting that attention must first be given to the spiritual origin(s) of violence before addressing any of the other issues" (Abegunde, 2011). Healing from this particular type of trauma is something that is very intergenerational, both physically and spiritually. The previous two points work in concert with this point because the self- protection is the immediate response to police professions assault on Black bodies, the intra-communal strategizing session was more short term because there must be a space held to critique and analyze potential solutions in a way that fosters community decision making across our intersections of class, gender, sexuality, etc. Lastly, the healing component itself is important because it is here where grief and affirmation are on full display. In regards to grief, Malidoma Some contends, If there is no expression of grief, it will affect the living and the dead detrimentally... it is the presence of community that validates the expression of grief. This means that a singular expression of grief is an incomplete expression of grief. A communal expression of grief has the power to send the deceased to the realm of the ancestors and to heal the hurt produced in the psyches of the living by the death of a loved one" (Some, 1993). In order to grasp or even approach the spiritual origin of centuries of trauma under the whip of the slave patrol to being in the crosshairs of a gun, there must be a time and space set just for that. Many of us cannot begin to conceive of grieving for those Black people we hear about on them on the news more than every hour. The practice proves too daunting or exhausting, occurring with such normalcy that ones choices often seem to be numbness or emotional overload. Grief is the process, particularly from an African cultural perspective that sets aside space for the human to process the unspeakable. I suggest the creation of rituals and practices rooted in the African traditions of the past. And the battleground the healing and the spiritual is the core because as African people our teleology or our definite purpose is not just material, but it is by definition ancestral. This article has engaged the topic of police professionalism from its inception to some examples of its contemporary manifestation. I am of the belief that if our goal is “liberation” and by liberation we use Amilcar Cabral’s definition of the returning of a people to their historic personality, combined with Danjuma Modupe’s Afrocentric concept of “Africana existence on Africana terms” then Africana people must begin to divest, if not yet physically, at least ideologically and morally from the belief that the police profession is anything more than a system that will only dehumanize Africana people for the sake of protecting the profits, financial and otherwise of white supremacy. No amount of “good-cops” or individuals “from the community” can change the nature of the police profession; hence the initial suggestions for alternative places for some engaged youth to direct their energy. One fundamental component of establishing Africana existence on Africana terms is listening to the suggestions Africana activists on the ground that are directly engaging the trauma of the police force and profession. I view this as the first stage in self-defense against the police, because the people most in tune with the self are those on the ground with their ear to the street. Some of the activists who should be contacted by those interested are Johnetta Elzie, DeRay McKesson, Erica Garner, Alicia Garza, Jasiri X, Cherelle Brown, Charlene Carruthers, as well as the following organizations: #BlackLivesMatter, Organization for Black Struggle, Millennial Activists United, New York Justice League, We Charge Genocide, and The Black Youth Project 100 among other organizations. Each of the activists named have first-hand on-the-ground experience both protesting and organizing against the police force from a position of Africana agency. Each of the organizations listed also have first -hand on-the-ground experience both protesting and organizing against the police force from the position of Africana agency. In this series of essays, I have offered both analysis and critique. On the macro level I am of the opinion that we must start from a position of agency as African people, not merely Negroes reacting to whiteness. This is both macro and fundamental because theory is, as Amilcar Cabral taught us, a weapon, and, as Bobby Wright taught us, “if you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.” So indeed, we must stand on firm cultural ground, be oriented towards Africa, and, as Molefi Asante reminds us, claim a victorious consciousness for our fellow Africana people and ourselves. However, on an existential level, I think, as Dr. Sonja Peterson Lewis states “You have to speak to the people, before you speak for the people.” Therefore, I would suggest starting with these activists and organizations I have listed in regards to on-the- ground direct action, as it is my judgment that their voices will be some of the most necessary, poignant, accountable, and accessible, which is precisely the starting point for any revolutionary movement; not pontificating from on high, but cultivating and crafting our tactics and perspectives from the Black grassroots.

0 Comments

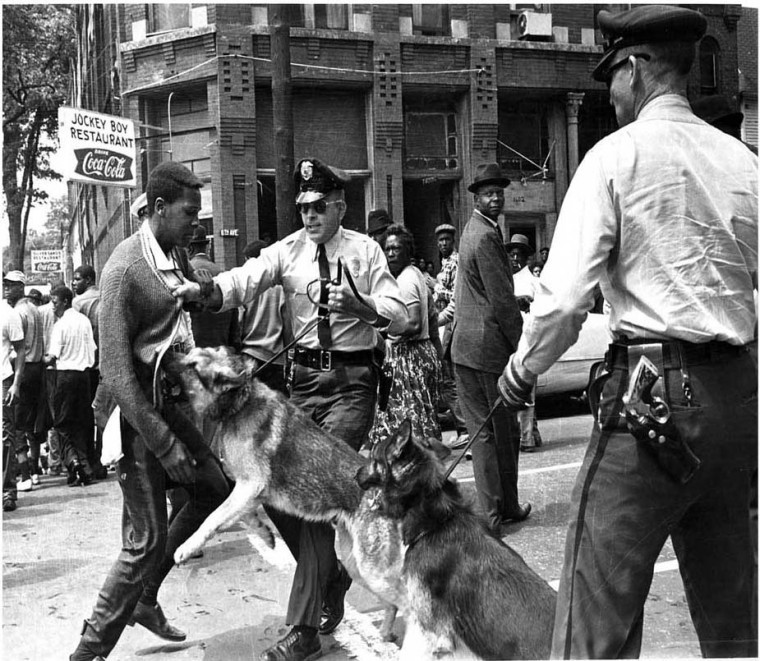

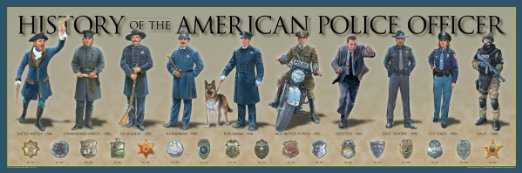

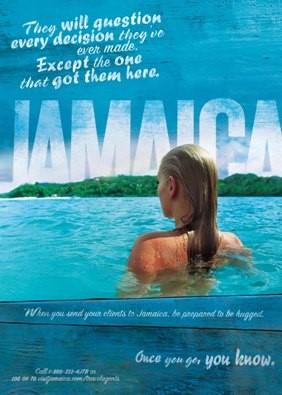

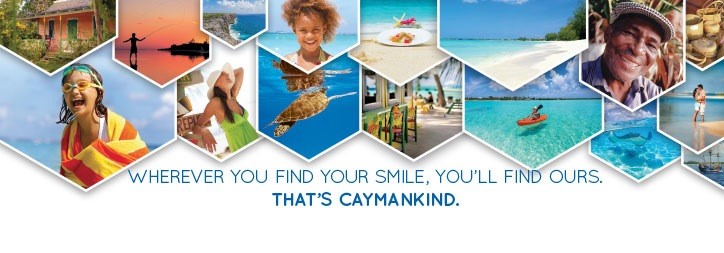

Are Police Obsolete? Part II: The Relationship between Police Departments and Slave Patrols4/24/2015 Written by Chris Roberts U.S. History of Police Departments The first police departments in the northern United States, Philadelphia (1833), New York, and Boston, all are based largely off Sir Robert Peele’s model and his nine operational principles. The particular situation in the States was the abundance of intra-ethnic strife between different European groups such as the Dutch, the Irish, and others. However, this was an external push factor that led to the implementation of those police departments, much in the same way the thieves in England were an external push factor. But it still was a subsidiary force in their creation, as the internal end of protecting white supremacist profit and dehumanization of Africana people via the slave trade still was the internal end of the profession in the United States, as it was in England. Many of the historians of the police in the United States would like to tell a narrative of the Northern departments a la Gangs of New York, a dedicated force of public servants dedicated to order and peace in their community amidst organized crime and mass riots. Those same historians will then juxtapose the Northern departments as therefore distinct from the overtly racist Ku-Klux-Klan minded gunslingers of the South, who openly sought to use the police concept to subjugate the “Negroes.” The fact of the matter is, that both the North and the South despised and ignored the Negro. The Black scholar W.E.B. DuBois explained profoundly the ethos of the Northern despise of the “Negro” particularly during the Civil War in his text Black Reconstruction: To the Northern masses the Negro was a curiosity, a sub-human minstrel, willingly and naturally a slave, and treated as well as he deserved to be. He had not sense enough to revolt and help Northern armies, even if they were trying to emancipate him, which they were not. The North shrank at the very thought of encouraging servile insurrection against the whites. Above all it did not propose to interfere with property. Negroes on the whole were considered inferior beings whose very presence in America was unfortunate (56). If it was indeed as DuBois articulates (which I assert it was), one must reach the conclusion that if such a fervent belief in the inherent inferiority of Black people consumed the white U.S. consciousness in the 1860s, there is no reason to believe that roughly thirty years prior when most of these Northern police departments were created and professionalized that such belief wasn’t just as, if not more prevalent. Therefore, the sub-human treatment of Black people by the police, government, law, and military was not an example of individual bad actors in Northern cities among an otherwise abolition and freedom minded mass of concerned white folk. Rather the protection of such sub-human treatment was necessary for the exacerbation of profit and construction of the United States as a global superpower that the enslaved African be present in the country. That said the entity most adept to protect the ability for white supremacy to treat Africana people in that manner was the police profession. The founders of the country never envisioned or wanted the “Negro” to be an equal contributor and member of the American republic. The “Negro presence” was particularly abhorrent to one of the most Northern, “forward-thinking” devout adherents to the idea of “America.” Benjamin Franklin, American polymath, politician, and founding father long held concept of the new country as an Edenic refuge and destination for white people. To understand this concept of Edenic one should look to the work of philosopher Benjamin Cocker in his following description: … commencement of an Edenic race in an Edenic centre, the calling into being of a specially endowed and Divinely instructed man, the covenant man, who was the figure of Him who was to come, that is, he was the type of Christ, the Teacher and Redeemer. The Edenic man appears as the instructor, the teacher of the prehistoric races. This is “the seed” through which God will elevate and bless the Turanian, the Khamite, the Negro. The Caucasian race, fix it as you may has always been the missionary race, the civilizing race, the educating race, in every age (110). With the Edenic centre as the United States, this concept of the white man as the instructor of the prehistoric can also be read as the slave patrol defense of “promoting honor and industry” among the enslaved. In each case, the white savior is required to punish, correct and bring those farther from him (also read as farther from Him and Eden) closer to him. Benjamin Franklin expressed “a longing that an ‘Edenic’ North America might become a production hub for the world’s “purely white people,” according to Singh. Given Franklin’s positioning of America as Eden, it was not, nor ever would be, in the eyes of such founders “fit” for those who do not bend to the benevolent guidance of the white saviors of the desolate of the world, among whom the “Negro” was the peak. The fate of those who refused to bend to the Edenic whims of the white ruling elite was to be broken, they would be “corrected,” and the institution of such correction was the slave patrol, the police profession. This subsection has sought to establish beyond reproach that the Northern conceptualization and professionalization of the police is rooted in the belief espoused, per Singh, by Benjamin Franklin that “The majority of Negroes are… cruel in the highest degree… [Franklin doubted that] mild laws could govern such people, which is to say that he affirmed the whiteness of police” (Singh. 2014). In the 21st century, we find ourselves square within the scope the same white supremacist police entity; it has just adjusted its appearance. It is as Malcolm X said, “racism is like a Cadillac, they bring out a new model every year.” The current model can be found in police departments such as, but not exclusive to, Cleveland, Oakland, Chicago, New York, and Ferguson. Though those are the ones listed, it is important that we understand, as Malcolm X also said, “everything under Canada is the South” so these new models of racism via policing are not the exceptions of the U.S., but they are the norm. U.S. History of Slave Patrols The planter class of enslavers, the ruling white elite in what began as the Thirteen Colonies, and eventually became the United States existed in a state of constant fear. According to historian Sally Haden in Slave Patrols, "Southern whites feared their slaves and needed mastery over them...though they tried to be vigilant, many whites lived in almost a 'crisis of fear' from one rumor of rebellion or insurrection to another" (6). Due to this they developed a public law enforcement entity of volunteers, and later employees, whose task it would be to ensure the order and proper behavior of the enslaved. In his turn of the 20th century work The Spawn of Slavery W.E.B. DuBois described this public law enforcement entity as “a system of rural police, mounted and on duty chiefly at night, whose work it was to stop the nocturnal wandering and meeting of slaves, it was usually an effective organization, [to] which all white men belonged” (DuBois. 1901a/1982). These rural police were known as slave patrols, and it is my assertion that they served as the teleological bedrock of what we know today as the police apparatus in the United States. Sally Haden states that patrols “were not created in a vacuum, but owed much to European institutions that served as the slave patrol’s institutional fore-bearers” (Haden. 2003). Haden continues by revealing that “in the South, the ‘most dangerous people’ who were thought to need watching were the slaves – they were the prime targets of patrol observation and capture. The history of police work in the South grows out of this early fascination… Most law enforcement was by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating Black slaves” (Haden. 2003). This background is important because we must understand the tactics of the police in their dehumanization of Black people today as not the isolated province of rogue cops, rather core components to the policing profession in the United States. The particular police system in South Carolina owes much of its structure to Barbados, as the majority of its first settler-colonialist came from there, with enslaved Africans in tow of course. Hadden states “Once a Caribbean patrol system existed that could be elaborated on, colonists in the Carolinas and Virginia developed their own distinctive slave patrols in the 18th century” (Haden. 2003). Given this information from Hadden, it now becomes clear that in the history of the United States and the Caribbean, the profession of slave patroller predated the profession of police officer, and therefore obviously played a major role in the Southern policeman archetype. These patrollers emerged initially as community members who all rallied around the collective desire for the “pursuit, capture, suppression, and punishment of runaway slaves” along with the “promoting of honesty and industry among the lowest class who are our slaves” (Hadden. 2003). In this South Carolina example one sees the double edged sword of the slave patrol, on one edge it “corrected” the flesh and on the other edge it “clamped” the mind, both truths contoured the Africana person into a state of, what Michael Tillotson calls, perpetual agency reduction. This reduction of Africana collective agency was a vital component of the slave patrol profession because equally as important as devaluing Africana life on Africana terms, the slave patrols served to protect whiteness, and position that protection as a collective responsibility, which reaches back to the Hegelian aim of the police as “care for the particular interest as common interest.” For the slave patrols, the particular interest was the dehumanizing of the African because that particularity was made a common interest by the way such dehumanization, reinforced whiteness. Nikhil Pal Singh defines whiteness as: a status conferring distinct—yet conjoined—social, political, and economic freedoms across a vertiginously unequal property order. A conscious assemblage, it was designed to extend, fortify, individualize, and equalize the government of public life in a world dominated by private property holders whose possessions included other human beings and lands already inhabited yet unframed by prior claims of ownership (1). These slave patrols operated for centuries killing, arresting, and dehumanizing Africana people on a regular basis. These law enforcement officers were legally empowered to whip, search, strip, rape, and beat Black people, Black women in particular. According to the history books, the slave patrols ended their practices after the Civil War for the most part, however, I assert that the slave patrol merged with the existing police profession, which was a different manifestation of the same teleology. The police profession today still values white supremacy and negates Africana humanity. Haden reminds us that the “…language used to describe slave patrols also permeated police activities long after patrols were gone. The ‘beat’ originally used as a geographic means of organizing slave patrol groups in South Carolina and other states, became the basic area that policeman supervised” (Haden. 2003). Additionally, we learn from the work of Haden that the “stakeout” tactic became professionalized in the police force due to it existing as a common practice in slave patrols. Written by Chris Roberts According to the team of activists running the website mappingpoliceviolence.org “At least 304 Black people were killed by the police in the United States in 2014.” According to The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, numbers like this average out to a Black person being killed extrajudicially by the police every 28 hours. There are some who believe that this amount of time between the killings of Black people by police has dipped to one every 21 hours in 2015. In the media, cases such as those highlighted in the aforementioned statistics are described as examples of police brutality. Cassandra Chaney and Ray Robertson in their article Racism and Police Brutality define police brutality as “the use of excessive physical force or verbal assault and psychological intimidation” (Chaney and Robertson. 2013). Though it is true that such treatment is brutal, I contend that such treatment is not a discernible departure from standard practice and function of the police. In the United States and much of the African world that has been pierced by the cutlass of European colonialism and white supremacy, policing by definition is brutal; there is no other form. To police Black/Africana/African people in the United States is to be brutal. This essay is the first in a three-part series that investigates how the concepts of "police and "policing" developed in Europe and traces the history of its colonial and contemporary applications to those of us who are Black/Africana/African in a manner that is brutal. This first essay focuses on the development of the concepts of “police” and “policing” as conceived in Europe. “To protect and serve” is the mantra of the Los Angeles Police Department and many others in the United States. However, upon further investigation it becomes painstakingly clear that this statement has selective applicability. The police protect the state along with its property, and the police serve whiteness vis-à-vis the continuation of white supremacy for the purpose of situating Black/Africana/African people as a criminal denomination of sub-humanity in need of eternal punishment and surveillance. Therefore, no level of reform or “change of culture” that is implemented to respective police departments or institutions, as long as they are in function and/or name “police” will shift the outcome of their work from being anything but the isolation and decimation of Black/Africana/African people and the protection of whiteness, by any costs and all means. European History of the Police The concept of a police force first emerged on the scene in the European world in France during the 10th century. This concept, polizei, was a meshing of “an artillery, a horse patrol, a foot patrol, watchmen” and a supervisor (provost) to enforce the law remained the model for a long time. Centuries later, during the reign of French King Louis XIV, Europe saw its first centralized national police force in 1667. The supervisor under Louis’ rule held the title of Lieutenant General, and this person was to “represent the state in the city… guarantee the security of Paris [and]… upgrade moral behavior” (Levinson. 2002). To ensure the preservation of that desired “moral behavior” from this system, the practice that Law scholar Jean Paul Brodeur describes as “high policing;” the gathering of intelligence about and suppression of potential threats to the society’s pre-existing distribution of power arose. It is from this “high policing” that one sees the justification of undercover agents and informants for the purposes of intelligence gathering and suppression. The European scholar Mark Neocleous posits that primarily “Polizei was concerned with the abolition of disorder” (Neocleous. 1998). A little over a century later, the first official, modern police department in Europe was created, the Thames River Police in 1798, which according to their museum’s website was “the first policing body ever to be set up. Its sole objective was the prevention and detection of crime on the Thames and it was to become the forerunner of many other police forces throughout the world,” New York’s Police Department among those influenced by Thames River Police. The creation of this department was spurred by loss of import dues by traders whose ships docked at the Pool of London and other areas along Thames River and theft at the ports. The same museum website describes the origins of the department by stating that with the “advice of Jeremy Bentham's legal knowledge, Mr. Patrick Colquhoun, LLD., the principle magistrate of Queens Square Police Office, Westminster convinced the West India Merchants, and the West India Planters Committees to finance the first preventative policing of the central shipping area of the Thames.” For our purposes, the important parties here are the West India Merchants and The West India Planters Committees because these were, according to the Museum of London, the raisers “of the capital that funded the building of the West India docks [which were]… the physical manifestation of London’s corner of the Triangle trade. The Dock was used by at least 22 know slave trading vessels.” Given this historical reality, once can see that the impetus for the professionalization of the police in the British context emerged directly out of a desire to preserve property and profit drenched in the blood and built on the bodies of enslaved Africans. The British profit from the Transatlantic trade of enslaved African people is the teleological bedrock of the police profession in England. And England is of particular import because it was the colonial governing body of the independent country that would become the United States. The Thames River Police would eventually merge with the Metropolitan Police Service. This second modern European police department was started in 1829 by Sir Robert Peele in England in Scotland Yard, and it began as a department that was to “manage the social conflict resulting from rapid urbanization and industrialization taking place in the city of London… focus primarily on crime prevention—that is, preventing crime from occurring instead of detecting it after it had occurred” (Archbold. 2012). The distinction of MPS here is crucial for two reasons. One, because it is from here where one finds the police department to which many departments in the Northern part of what we now know of as the United States (states above Maryland) modeled themselves after. Two, the professionalization of policing via Sir Robert Peele’s uniform implementation and nine principles combined with the public sense of self as connected to the police. In particular, his principle of “…the historic tradition that the police are the public and that the public are the police, the police … give full time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence” is imperative to understanding the teleology of U.S. policing, especially in the South. European Teleology of Police via Hegel The following section will be a discussion based in European philosophical thought because the police, both profession and concept, as we know them are Eurocentric, therefore the culturally congruent perspectives for discussing their sense of directedness are European. It should be understood on the part of the reader that Eurocentric philosophy has been utilized to justify the enslavement of Africana people for centuries, and the philosophy engaged in this subsection has been causal and complicit in that oppression of Africana people. Teleology in the words of the European philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel is “the truth of mechanism.” The author Christopher Yeomans describes this as Hegel critiquing mechanism and implying [in regards to an object or thing] “the means’ own nature is itself an end. The state of an object worked on by an external end can only be understood as external with respect to some immanent end of the object” (Yeomans 2011). In other words, a thing does not operate independent of the desired destination or outcome it was made to reach, and that “internal end” must be explicated to fully understand the thing. In our example, that thing is the police. This is a vital point because it is here where the “internal end” of the police concept is explained, and I assert that the police profession is a thing cannot go against its internal end, its very nature. For Hegel, as articulated in the research of Mark Neocleous, the internal end or “aim of the police [is to] care for the particular interest as a common interest.” (Neocleous.1998). In Policing The System of Needs: Hegel, Political, Economy, and the Police of the Market one learns that the main interest of the police, according von Justi, a contemporary of Hegel’s was: … maintenance of state power and the proper police of the market …ultimately, the same goal. In this sense the main interest of police was the development of commerce and the production of wealth. For von Justi, ‘all the methods whereby the riches of the state may be increased, insofar as the authority of the government is concerned, belong consequently under the charge of the police.’ To this end the state should secure a flourishing trade and devote its power to the preservation and increase of the resources of private persons in particular and the state of prosperity in general, by overseeing the foundations of commerce (46). With the “production of wealth” as its objective, the only thing needed for the police was a “flourishing trade” that would serve to increase the “resources of private persons in particular and the state of prosperity in general.” One such trade was indeed prevalent and in full swing, that being the Transatlantic Slave Trade of hundreds of millions of enslaved Africans, throughout which the African continent was raped and tens of millions of Africana people were killed at the hands of Europeans. This genocide is referred to by Africana Studies scholars as The Maafa or African Holocaust, a term which was operationalized by African Psychologist Marimba Ani. One has to understand this in order to confront the reality that the police are something much more insidious than a public force with individual racists who equate to nothing more than a few rotten apples in what overall is a good, well intentioned batch of people. But rather, the reality of the situation is that the police profession was created in England for, to use Hegel’s term, the “particular interest” of protecting the sugar, rum, salt, and other assets of European capitalism in the Caribbean that were all gained due to the enslavement of Africana people which served the “common interest” of whiteness and its benefactors (white people). No amount of good will or good intention can change the truth of this statement. The police profession may have arrested plenty of white thieves in England who stole sugar, rum, or salt. However, those thieves were not the reason the police force was created and professionalized; it was the profit and exploitation their theft cut into that prompted the creation and professionalization of the police force. The arrest of those thieves was simply a by-product of the overarching concern of the police force to protect white supremacy and the profits of the Maafa enjoyed by Europe. In the minds of the white philosophical elite this concern for profit did not equate in a justification of the Maafa/enslavement of Africana people. Jeremy Bentham, the European philosopher whose advice and legal insight was foundational in Patrick Colquhoun founding and professionalization of the Thames River Police is one such white philosopher. Bentham is regarded in much of European history as an abolitionist, however his brand of abolition was not abolition at all in my estimation, but rather a gradual road to nowhere, a la the “all deliberate speed” U.S. Supreme Court ruling on segregation in the 1950s. In the essay British Utilitarianism’s Justification of Negro Slavery Nathaniel Adam Tobias writes: “this abolition could take place without overturning their [those who enslaved and traded other persons] own condition and their fortunes, and without attacking their personal security… This operation need not be suddenly carried into effect by a violent revolution, which, by displeasing every body, destroying all property, and placing all persons in situations for which they were not fitted, might produce evils a thousand times greater than all the benefits that can be expected from it. Tobias continues when he explains Bentham’s distinction between “slave-buying” and “slave-holding” insofar as slave-buying, or “plunging” people into slavery is worse than “finding” people already in slavery. In other words, from this Eurocentric perspective Black people were not “plunged into slavery” but rather they were “discovered being inferior and ignorant” therefore Europeans of Bentham’s time “find” them enslaved not because white people had chosen to enslave them, but rather enslavement is where white society “found” them. ” (Tobias 3). The concept of policing is to ensure the stability of social order, and the police, by definition in a white supremacist society, maintain that white supremacist social order. In the minds of the structural architects of policing such as Bentham, the police forces of today are not “buying” or “plunging” people into an enslaved position in society, rather the police force is “finding” Black people in that status already, and maintaining order, which by definition is antithetical to the Black people who “find” themselves in slavery ever “finding” themselves in anything different. To concretize this point I will return to Hegel, the protection of the profits of white supremacy and its necessary dehumanization via enslavement of Africana people to exacerbate those profits is not merely an end that is sometimes met via the police, but rather it is the internal end, it is “the truth of the mechanism” that is the police profession. Written by Mikana Scott “Once you go, you know” and “Wherever you find your smile, you’ll find ours” are two slogans that have been or are currently being used by the Jamaican Tourist Board and the Cayman Islands Department of Tourism. In 2013, tourism comprised of 28.5% (USD $4 billion) of Jamaica’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2013 and 25.4% (KYD $713.1 million) of Cayman’s GDP. Tourism as defined by the United Nations World Tourism Organization is, “a social, cultural and economic phenomenon which entails the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes.” For the Caribbean region as a whole, reports state that the total impact of tourism in 2014 can be estimated at 14% of GDP at $49 billion. However, scholars have noted that there are many Caribbean islands that rely heavily on tourism such as Antigua, a former British colony that relies on 70% of its GDP/income from tourism. The Bahamas (former British Colony), Aruba (Dutch Constituent) and Barbados’ (former British colony) economy relies on 50% of tourism contribution as do other islands (Conway 114). For many Caribbean countries, tourism is an important sector, with most of their economy based on it. While Caribbean countries garner substantial income from the tourist industry, analysis must be done on the direct beneficiaries as well as the costs/impacts associated with this specific sector. This article will focus on the English speaking Caribbean, specifically countries that were former British colonies. History of Tourism in the Region During the mid to late 1900s tourism within the Caribbean has developed rapidly, aided by modern technology and transportation. However, origins of the tourism industry in the Caribbean go back to the late 1800s. Taylor credits the banana trade with the US and the use of banana boats that carried Americans to Caribbean countries (Jamaica especially) as the starting point. Additionally, banana companies were the first proprietors of hotels in the region (qtd. in Miller 36). Tourism that we know today, a mass, standard experience began in the mid-1900s is described by Duval as being a period of “undifferentiated products, origin-packed holidays, spatially concentrated planning of facilities, resorts and activities, and the reliance upon developed markets such as the US, Canada and Britain” (qtd. in Williams 192). This mass tourism comes in 2 different forms - the coastal beach resort and cruise ship packages. These experiences are known as ‘3s’ - sun, sand and sea tourism (Goodwin, 4). Leisure and recreation are the primary reasons for persons from North America and Europe visiting the Caribbean and since the 1950s this has increased substantially. During this period Caribbean countries were also beginning to agitate for political independence from their colonizers. Many of these governments were unable to finance the enhancement of their tourism product by themselves. Therefore, Western lending agencies such as development banks and international organizations such as the World Bank financed these projects which included large hotels (Williams 193). Western agencies such as the International Money Fund (IMF) believed that tourism was an economy that would help these small islands that did not produce significant agriculture or have natural resources to export. Additionally, they foresaw tourism assisting in diversifying the economies of islands (such as Jamaica) that had a lot of debt. Agreements with Western lending agencies have had two lasting impacts that are felt in the region to this day: 1) Through the IMF and its Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), Caribbean governments incurred substantial debt, which led to their reliance on these institutions, forcing them to ‘adjust’ their economic and social structures to the liking of European and American institutions. 2) The Third Lome Convention (1986-90) according to Patullo, concretized Europe’s relationship with countries on the African continent, the Caribbean as well as those in the Pacific. While it supported Caribbean countries expanding the tourism sector, it also tied politically independent countries with their former colonizers (qtd in Williams 193). Neo-Colonialism Kwame Nkrumah defines neo-colonialism as “that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.” (qtd. in Biney 127). Another definition states that power is taken from local and regional entities and is concentrated in foreign owned companies (Williams 191). What does neocolonialism mean in the Caribbean context as it relates to the tourism industry? These newly independent countries had the expectation of political and economic freedom; however, this was not possible within the parameters of the tourism industry. Neocolonialism is an occurrence when the natural resources, culture and even citizens are commodified for the enjoyment, pleasure and leisure for a majority of Europeans and North Americans visitors. The Word Tourism Organization (WTO) reports that by 2020, a quarter of the world’s population (1.95 billion) will take a trip overseas. The majority of these tourists however are from the US, UK, France, Germany and Japan. In the Caribbean the tourism industry is comprised of white management, white American and European guests, low wage majority black local labor, with profits being made by overseas international firms (Bennett & Gebhardt 15). Williams (191) posits that historically the region historically has been the subject of mass exploitation. Whereas during the enslavement period it was agricultural production for Western markets in the form of sugar and cocoa, today tourism is a new form of colonial relationship. While the countries in the region have different languages and ethnicities due to colonization, they have engaged in similar production sectors that have greatly changed their environment: “plantation agriculture, mining and tourism” (Baver & Lynch 3). It was believed that focusing on tourism would enable these newly politically independent economies to diversify their economies and break away from the sectors they relied upon during the colonial period (Williams 192), however in discussing the costs and impacts of tourism in the region we see that is not the case. Ownership Management of the tourism industry is largely in the hands of others. While there are small locally owned hotels they are vastly outnumbered by the majority of large, multinational hotels. Hotels and restaurants do contribute to local employment, but many local / Africana persons are employed in lower paid jobs such as housekeeping and food preparation, while white expatriates are found in managerial positions (Williams 194). Infrastructure was financed by foreign investment with there being lower import duties on equipment and raw materials in trying to appeal to overseas business. Therefore it was/has been more profitable for investors than for the islands who gave them import cost breaks. Additionally beneficial relationships for foreign airlines and tour operators had to be arranged (Williams 193). Closed Economies Due to many vacation packages being “all inclusive” and all expenses paid, there are few tourists that leave their hotels and pay for goods and services from the local community. All-inclusive travel packages were seen as the solution to tourists’ fears of ‘crime’ and ‘harassment,’ however this results in a closed economy owned by overseas corporations. Money is not injected into the local economy and Mullings even goes as far as to state that tourists are told that tips are ‘not necessary’ therefore even less money is able to be circulated in the local Caribbean economy (qtd. in Williams 196). Many all-inclusive packages also provide their own transportation, souvenir stores, entertainment and recreational activities. This greatly disadvantages local taxi drivers, vendors and craftsmen who rely on tourism as a means of employment. Additionally, local business owners are shut out of the economy, as the primary institutions: airlines, tour operators, travel agents, hotel operators are ‘largely owned, controlled and managed outside of the region’ (Williams 196). Mullings makes the connection that this is reminiscent of the colonial economies of the Caribbean, when European countries externally controlled islands’ affairs (qtd in Williams, 196). Therefore this closed economy results in local culture being diminished due to foreign influence, with these vacations becoming a European/American version of the Caribbean (Williams 195). Dynamics Examining the ways black bodies are portrayed, the smiling waiters, the gentle way hairdressers’ braid cornrows into European women’s hair, Patullo states that from its origin, tourism has echoed the enslavement period. There is a folk memory and collective remembrance of African people ‘serving’ Europeans for hundreds of years during the enslavement period, however now they are doing it for hourly wages (qtd. in Williams 196). This paints a picture of how marginalizing and demeaning the industry is to the African collective psyche. UWI Professor Hilary Beckles, after analyzing the relationship between the business elite, the state and citizens, is of the opinion that tourism is the ‘new plantocracy’ (qtd Williams 196). There are a select group of persons that own the majority of infrastructure in the industry, and it is posited that black people are still marginalized in their own country. While Africana people are the majority of the labor in this industry, they are not included in the decision making process (due to multinational corporations owning the land, commercial interests, ports and duty free outlets) (Patullo, 65 qtd. in Williams 196). The Caribbean is 4 times more dependent on tourism than any other region in the world (Daniel 72). Yet, the majority of the profits ends up with foreign investors. Additionally, tourism strategy is determined by the global economy. Globalization increases difficulty for individual governments to intervene and manage the industry as these countries ‘have minimal control over the disposition of their resources’ (Miller 35). This is due to the region’s weak position in the global economy as it has always been shaped by external forces: the enslavement period and plantation agriculture, labor migration, colonization and contract farming, mineral extraction and now tourism. Natural Resources Scholars are in agreement that tourism harms the environment, as it decreases the capacity of an area to handle man-made wastes. Harbors are also dredged and coastal environments disrupted to build hotels and resorts. Additionally, water contamination is a problem, as large hotels are the prime source. There are also issues of pollution, human waste, destruction of mangroves and coral reefs (Miller 37). On a larger scale, the Caribbean is dealing with deforestation (Haiti is experiencing desertification), urbanization, air & water pollution and destruction of coastal ecosystem (Baver &Lynch 5). Due to the small size of the islands and the importance of a vibrant ecosystem one would expect stringent environmental policies and laws. However instead of adopting protectionist measures, tourism has played an integral role in the exploitation of the environment. When environmental regulation and enforcement is put in place, they often serve the tourism industry and real estate development, often at the expense of citizens (Baver &Lynch 6). In Jamaica it is stated that by 1992 all but nineteen of the island’s four hundred and eighty eight miles of coastline had been privatized (Goodwin 9). Ecotourism is a new trend in the tourism industry which has occurred due to environmental damage as well as expansion (since tourism is a capitalistic system). However these beautiful landscapes are created by excluding local residents Miller (37). This new, ‘holistic approach’ to mass tourism is often seen at odds with the community, as issues of access, privatization and enclosure of natural resources are often geared toward tourists and not the local community (Baver & Lynch 14). Images of clean pristine beaches, free from pollution and also the ‘aggressive’ local peddlers, raise concerns about usage. For the tourism industry the solution is often to control the access. Therefore public parks, are not for the local public at all, but for tourists. While there are forms of ecotourism that are locally initiated and managed, there are limited effort to support those businesses / activities. It is instead assumed that benefits will trickle down through employment.  The land and environment that communities used to use for fishing, firewood and subsistence resources are now essentially for tourists only (Miller 38). No longer is the land that was used for agricultural purposes and the coastline for fishing and recreation available to the public or locally owned, but rather for a select (majority white) overseas population. According to Sheller, “the picturesque vision of the Caribbean continues to be a form of world-making which allows tourists to move throughout the Caribbean and see Caribbean people simply as scenery” (qtd in Baver & Lynch 8). Culture as Performance Many persons that visit the Caribbean are there to enjoy the natural beauty, the relaxation and the stress free activities. However for others, Caribbean culture is seen as exciting and enticing. Historical buildings, cultural practices, public festivals as well as the population interest certain tourists (Daniel 170). Junkanoo in the Bahamas, Carnival in Trinidad & Tobago and Jamaica, Batabano in the Cayman Islands are just some of the festivals that are celebrated throughout the year. It is posited however that in the context of globalization and cultural identity, tourism is representative of ‘inauthenticity and alienation’. By concretizing Caribbean culture it attempts to redefine and package practices and natural resources as ‘commodified spectacle’ and a rigid experience (Bennet & Gebhardt 15). Not only is this presented to the tourist, but the local population relearns their history and celebrations through a lens not created for or by them. For Jamaican cultural icon and scholar Rex Nettleford, in describing Trinidad Carnival and Gombey in Bermuda he isn’t concerned about the commodification of those events. He chooses to focus on local Caribbean needs and tastes first, and tourists secondly. He attempts to reclaim Carnival and place it within Caribbean culture, and then if necessary as a tourist phenomena (qtd. in Bennet and Gebhardt 16).

Opposition to this can be found within cultural studies as some argue that this type of tourism can be foundational to policy that assists in forming a country’s cultural identity. However, this type of inauthentic practice will only facilitate in building a ‘simulated’ culture base for these Caribbean countries (Benet & Gebhardt 16). Furthermore in citing Homi Bhabha’s ‘mongrelity’ of culture, scholars state that this will reiterate this modern whitewashing of African culture in the Caribbean, and frame it as racial and cultural hybrid. This passive hybridity has been adopted by local elites to attract tourism, which benefits their interests more than the majority of citizens (Benet & Gebhardt 17). Tourism as Anti-Liberatory In examining this palatable way in which Blackness/Africanness has to be mixed and presented as Caribbean creole or hybrid, Joel Streiker states that this helps economic interests of local elites as it reassures white European tourists who see Blackness as ‘threatening’. This passivity which masks racial discrimination and class politics discourages political organization around Blackness, and according to Streiker “..hybridity forms part of a strategy of domination rather than liberation..” (qtd. in Bennet and Gebhart 18). Not only is there a suppression of Blackness, but there are also demands of the population to present themselves in a pleasing way to tourists (Miller 40). The local population must always be courteous and pleasant, therefore Africana people are seen as important components of the Caribbean brand, as long as they are creole smiling people. There are many components that make up the tourism industry. All aspects of society are affected: economically, environmentally and culturally. Since the beginning of the tourism product, development has been influenced by outside multinational corporations and organizations. Therefore what does that mean for a self-sustaining and self-sufficient Caribbean? Conclusion For Africana persons living in the Caribbean and in the larger African diaspora, in depth conversations about the concept of tourism and the tourism industry must be had. Alternative ways of analyzing the industry and understanding how Africana people are affected by this sector of the economy must be done. For many Caribbean people, growing up in a tourist destination is seen as a normal occurrence and for many employment within the industry is seen as preferential. Countries that still have colonial ties cannot achieve true independence if these linkages are not made. Additionally, for African persons traveling to the Caribbean, a deeper understanding of the tourism industry and the ways we unknowingly contribute to the degradation of Africana people needs to be had as well. Additionally scholarship within Africana studies must be produced that focus on this phenomena. For the most part scholars are located in Hospitality & Tourism Studies, Political Ecology, Environmental Studies, Cultural Studies and Anthropology. It is extremely problematic when Africana people in the Caribbean are continually referred to as ‘other,’ and when concepts such as ‘modernity’ are tied to travel (with travelers meaning white European and white American). Cultural transmission is still discussed in many works as going from center to margin - with Caribbean people being the margin. These are ideological problems that must be identified and corrected from and by African people. Africana Studies, in researching and writing about phenomena occurring wherever African people are present must be in these conversations. Archaic and racist constructs must not be present when we are understanding the tourism industry as it affects many Africana people in the Caribbean. For traveling Africana people making connections within the Diaspora, utilizing travel companies such as Travel Noire, African Diaspora Tourism, or organizations such as Afrocentricity International that frequently hold conventions within the African Diaspora is important in combatting the oppressive ways tourism functions. Continuation of concentration of ownership, infrastructure, access to natural resources and policing Africana culture and bodies by Western entities have all contributed to the pacification and false liberation of Africans in the Caribbean. Control of narratives, cultural practices and ownership on African terms is essential for the de-commodication of Caribbean countries and Caribbean peoples. Works Cited Baver, Sherrie L. and Barbara Deutsch Lynch. “The Political Ecology of Paradise.” Beyond Sun and Sand. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006. JSTOR. Web. 16 March 2015. Bennett, David and Sophie Gebhardt. “Global Tourism and Caribbean Culture.” Caribbean Quarterly, Vol 51, No. 1, March 2005: 15-24. 15 March 2015. Biney, Ama. “The Intellectual and Political Legacies of Kwame Nkrumah.” The Journal of Pan African Studies, Vol 4, No 10, January 1012: 127-142. 19 March 2015. Conway, Dennis. “Tourism, Agriculture, and the sustainability of terrestrial ecosystems in small islands” Island Tourism and Sustainable Development: Caribbean, Pacific and Mediterranean Experiences. Google books. Westport: Greenwood Publshing, 2002. Google Books. Web 20 March 2015. Daniel, Yvonne. “Tourism, Globalization, and Caribbean Dance.” Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2011. JSTOR. Web. 17 March 2015. Goodwin, James. “Sustainable Tourism Development in the Caribbean Islands Nation-States.” Michigan Journal of Public Affairs, Vol 5, 2008:1-16, March 2015. Miller, Marian A. L. “Paradise Sold. Paradise Lost: Jamaica’s Environment and Culture in the Tourism Marketplace” Beyond Sun and Sand. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006. JSTOR. Web. 15 March 2015. Williams, Tammy Ronique. “Tourism as Neo-colonial Phenomenon: Examining the Works of Patullo & Mullings.” Caribbean Quilt, Vol 2, 2012: 191-200. 14 March 2015. Written by Serie McDougal |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed