|

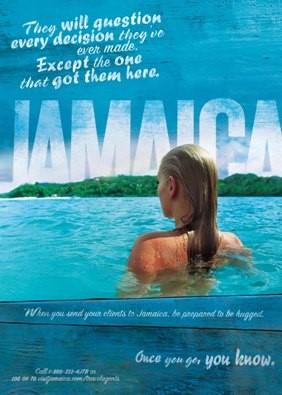

Written by Mikana Scott “Once you go, you know” and “Wherever you find your smile, you’ll find ours” are two slogans that have been or are currently being used by the Jamaican Tourist Board and the Cayman Islands Department of Tourism. In 2013, tourism comprised of 28.5% (USD $4 billion) of Jamaica’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2013 and 25.4% (KYD $713.1 million) of Cayman’s GDP. Tourism as defined by the United Nations World Tourism Organization is, “a social, cultural and economic phenomenon which entails the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes.” For the Caribbean region as a whole, reports state that the total impact of tourism in 2014 can be estimated at 14% of GDP at $49 billion. However, scholars have noted that there are many Caribbean islands that rely heavily on tourism such as Antigua, a former British colony that relies on 70% of its GDP/income from tourism. The Bahamas (former British Colony), Aruba (Dutch Constituent) and Barbados’ (former British colony) economy relies on 50% of tourism contribution as do other islands (Conway 114). For many Caribbean countries, tourism is an important sector, with most of their economy based on it. While Caribbean countries garner substantial income from the tourist industry, analysis must be done on the direct beneficiaries as well as the costs/impacts associated with this specific sector. This article will focus on the English speaking Caribbean, specifically countries that were former British colonies. History of Tourism in the Region During the mid to late 1900s tourism within the Caribbean has developed rapidly, aided by modern technology and transportation. However, origins of the tourism industry in the Caribbean go back to the late 1800s. Taylor credits the banana trade with the US and the use of banana boats that carried Americans to Caribbean countries (Jamaica especially) as the starting point. Additionally, banana companies were the first proprietors of hotels in the region (qtd. in Miller 36). Tourism that we know today, a mass, standard experience began in the mid-1900s is described by Duval as being a period of “undifferentiated products, origin-packed holidays, spatially concentrated planning of facilities, resorts and activities, and the reliance upon developed markets such as the US, Canada and Britain” (qtd. in Williams 192). This mass tourism comes in 2 different forms - the coastal beach resort and cruise ship packages. These experiences are known as ‘3s’ - sun, sand and sea tourism (Goodwin, 4). Leisure and recreation are the primary reasons for persons from North America and Europe visiting the Caribbean and since the 1950s this has increased substantially. During this period Caribbean countries were also beginning to agitate for political independence from their colonizers. Many of these governments were unable to finance the enhancement of their tourism product by themselves. Therefore, Western lending agencies such as development banks and international organizations such as the World Bank financed these projects which included large hotels (Williams 193). Western agencies such as the International Money Fund (IMF) believed that tourism was an economy that would help these small islands that did not produce significant agriculture or have natural resources to export. Additionally, they foresaw tourism assisting in diversifying the economies of islands (such as Jamaica) that had a lot of debt. Agreements with Western lending agencies have had two lasting impacts that are felt in the region to this day: 1) Through the IMF and its Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), Caribbean governments incurred substantial debt, which led to their reliance on these institutions, forcing them to ‘adjust’ their economic and social structures to the liking of European and American institutions. 2) The Third Lome Convention (1986-90) according to Patullo, concretized Europe’s relationship with countries on the African continent, the Caribbean as well as those in the Pacific. While it supported Caribbean countries expanding the tourism sector, it also tied politically independent countries with their former colonizers (qtd in Williams 193). Neo-Colonialism Kwame Nkrumah defines neo-colonialism as “that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.” (qtd. in Biney 127). Another definition states that power is taken from local and regional entities and is concentrated in foreign owned companies (Williams 191). What does neocolonialism mean in the Caribbean context as it relates to the tourism industry? These newly independent countries had the expectation of political and economic freedom; however, this was not possible within the parameters of the tourism industry. Neocolonialism is an occurrence when the natural resources, culture and even citizens are commodified for the enjoyment, pleasure and leisure for a majority of Europeans and North Americans visitors. The Word Tourism Organization (WTO) reports that by 2020, a quarter of the world’s population (1.95 billion) will take a trip overseas. The majority of these tourists however are from the US, UK, France, Germany and Japan. In the Caribbean the tourism industry is comprised of white management, white American and European guests, low wage majority black local labor, with profits being made by overseas international firms (Bennett & Gebhardt 15). Williams (191) posits that historically the region historically has been the subject of mass exploitation. Whereas during the enslavement period it was agricultural production for Western markets in the form of sugar and cocoa, today tourism is a new form of colonial relationship. While the countries in the region have different languages and ethnicities due to colonization, they have engaged in similar production sectors that have greatly changed their environment: “plantation agriculture, mining and tourism” (Baver & Lynch 3). It was believed that focusing on tourism would enable these newly politically independent economies to diversify their economies and break away from the sectors they relied upon during the colonial period (Williams 192), however in discussing the costs and impacts of tourism in the region we see that is not the case. Ownership Management of the tourism industry is largely in the hands of others. While there are small locally owned hotels they are vastly outnumbered by the majority of large, multinational hotels. Hotels and restaurants do contribute to local employment, but many local / Africana persons are employed in lower paid jobs such as housekeeping and food preparation, while white expatriates are found in managerial positions (Williams 194). Infrastructure was financed by foreign investment with there being lower import duties on equipment and raw materials in trying to appeal to overseas business. Therefore it was/has been more profitable for investors than for the islands who gave them import cost breaks. Additionally beneficial relationships for foreign airlines and tour operators had to be arranged (Williams 193). Closed Economies Due to many vacation packages being “all inclusive” and all expenses paid, there are few tourists that leave their hotels and pay for goods and services from the local community. All-inclusive travel packages were seen as the solution to tourists’ fears of ‘crime’ and ‘harassment,’ however this results in a closed economy owned by overseas corporations. Money is not injected into the local economy and Mullings even goes as far as to state that tourists are told that tips are ‘not necessary’ therefore even less money is able to be circulated in the local Caribbean economy (qtd. in Williams 196). Many all-inclusive packages also provide their own transportation, souvenir stores, entertainment and recreational activities. This greatly disadvantages local taxi drivers, vendors and craftsmen who rely on tourism as a means of employment. Additionally, local business owners are shut out of the economy, as the primary institutions: airlines, tour operators, travel agents, hotel operators are ‘largely owned, controlled and managed outside of the region’ (Williams 196). Mullings makes the connection that this is reminiscent of the colonial economies of the Caribbean, when European countries externally controlled islands’ affairs (qtd in Williams, 196). Therefore this closed economy results in local culture being diminished due to foreign influence, with these vacations becoming a European/American version of the Caribbean (Williams 195). Dynamics Examining the ways black bodies are portrayed, the smiling waiters, the gentle way hairdressers’ braid cornrows into European women’s hair, Patullo states that from its origin, tourism has echoed the enslavement period. There is a folk memory and collective remembrance of African people ‘serving’ Europeans for hundreds of years during the enslavement period, however now they are doing it for hourly wages (qtd. in Williams 196). This paints a picture of how marginalizing and demeaning the industry is to the African collective psyche. UWI Professor Hilary Beckles, after analyzing the relationship between the business elite, the state and citizens, is of the opinion that tourism is the ‘new plantocracy’ (qtd Williams 196). There are a select group of persons that own the majority of infrastructure in the industry, and it is posited that black people are still marginalized in their own country. While Africana people are the majority of the labor in this industry, they are not included in the decision making process (due to multinational corporations owning the land, commercial interests, ports and duty free outlets) (Patullo, 65 qtd. in Williams 196). The Caribbean is 4 times more dependent on tourism than any other region in the world (Daniel 72). Yet, the majority of the profits ends up with foreign investors. Additionally, tourism strategy is determined by the global economy. Globalization increases difficulty for individual governments to intervene and manage the industry as these countries ‘have minimal control over the disposition of their resources’ (Miller 35). This is due to the region’s weak position in the global economy as it has always been shaped by external forces: the enslavement period and plantation agriculture, labor migration, colonization and contract farming, mineral extraction and now tourism. Natural Resources Scholars are in agreement that tourism harms the environment, as it decreases the capacity of an area to handle man-made wastes. Harbors are also dredged and coastal environments disrupted to build hotels and resorts. Additionally, water contamination is a problem, as large hotels are the prime source. There are also issues of pollution, human waste, destruction of mangroves and coral reefs (Miller 37). On a larger scale, the Caribbean is dealing with deforestation (Haiti is experiencing desertification), urbanization, air & water pollution and destruction of coastal ecosystem (Baver &Lynch 5). Due to the small size of the islands and the importance of a vibrant ecosystem one would expect stringent environmental policies and laws. However instead of adopting protectionist measures, tourism has played an integral role in the exploitation of the environment. When environmental regulation and enforcement is put in place, they often serve the tourism industry and real estate development, often at the expense of citizens (Baver &Lynch 6). In Jamaica it is stated that by 1992 all but nineteen of the island’s four hundred and eighty eight miles of coastline had been privatized (Goodwin 9). Ecotourism is a new trend in the tourism industry which has occurred due to environmental damage as well as expansion (since tourism is a capitalistic system). However these beautiful landscapes are created by excluding local residents Miller (37). This new, ‘holistic approach’ to mass tourism is often seen at odds with the community, as issues of access, privatization and enclosure of natural resources are often geared toward tourists and not the local community (Baver & Lynch 14). Images of clean pristine beaches, free from pollution and also the ‘aggressive’ local peddlers, raise concerns about usage. For the tourism industry the solution is often to control the access. Therefore public parks, are not for the local public at all, but for tourists. While there are forms of ecotourism that are locally initiated and managed, there are limited effort to support those businesses / activities. It is instead assumed that benefits will trickle down through employment.  The land and environment that communities used to use for fishing, firewood and subsistence resources are now essentially for tourists only (Miller 38). No longer is the land that was used for agricultural purposes and the coastline for fishing and recreation available to the public or locally owned, but rather for a select (majority white) overseas population. According to Sheller, “the picturesque vision of the Caribbean continues to be a form of world-making which allows tourists to move throughout the Caribbean and see Caribbean people simply as scenery” (qtd in Baver & Lynch 8). Culture as Performance Many persons that visit the Caribbean are there to enjoy the natural beauty, the relaxation and the stress free activities. However for others, Caribbean culture is seen as exciting and enticing. Historical buildings, cultural practices, public festivals as well as the population interest certain tourists (Daniel 170). Junkanoo in the Bahamas, Carnival in Trinidad & Tobago and Jamaica, Batabano in the Cayman Islands are just some of the festivals that are celebrated throughout the year. It is posited however that in the context of globalization and cultural identity, tourism is representative of ‘inauthenticity and alienation’. By concretizing Caribbean culture it attempts to redefine and package practices and natural resources as ‘commodified spectacle’ and a rigid experience (Bennet & Gebhardt 15). Not only is this presented to the tourist, but the local population relearns their history and celebrations through a lens not created for or by them. For Jamaican cultural icon and scholar Rex Nettleford, in describing Trinidad Carnival and Gombey in Bermuda he isn’t concerned about the commodification of those events. He chooses to focus on local Caribbean needs and tastes first, and tourists secondly. He attempts to reclaim Carnival and place it within Caribbean culture, and then if necessary as a tourist phenomena (qtd. in Bennet and Gebhardt 16).

Opposition to this can be found within cultural studies as some argue that this type of tourism can be foundational to policy that assists in forming a country’s cultural identity. However, this type of inauthentic practice will only facilitate in building a ‘simulated’ culture base for these Caribbean countries (Benet & Gebhardt 16). Furthermore in citing Homi Bhabha’s ‘mongrelity’ of culture, scholars state that this will reiterate this modern whitewashing of African culture in the Caribbean, and frame it as racial and cultural hybrid. This passive hybridity has been adopted by local elites to attract tourism, which benefits their interests more than the majority of citizens (Benet & Gebhardt 17). Tourism as Anti-Liberatory In examining this palatable way in which Blackness/Africanness has to be mixed and presented as Caribbean creole or hybrid, Joel Streiker states that this helps economic interests of local elites as it reassures white European tourists who see Blackness as ‘threatening’. This passivity which masks racial discrimination and class politics discourages political organization around Blackness, and according to Streiker “..hybridity forms part of a strategy of domination rather than liberation..” (qtd. in Bennet and Gebhart 18). Not only is there a suppression of Blackness, but there are also demands of the population to present themselves in a pleasing way to tourists (Miller 40). The local population must always be courteous and pleasant, therefore Africana people are seen as important components of the Caribbean brand, as long as they are creole smiling people. There are many components that make up the tourism industry. All aspects of society are affected: economically, environmentally and culturally. Since the beginning of the tourism product, development has been influenced by outside multinational corporations and organizations. Therefore what does that mean for a self-sustaining and self-sufficient Caribbean? Conclusion For Africana persons living in the Caribbean and in the larger African diaspora, in depth conversations about the concept of tourism and the tourism industry must be had. Alternative ways of analyzing the industry and understanding how Africana people are affected by this sector of the economy must be done. For many Caribbean people, growing up in a tourist destination is seen as a normal occurrence and for many employment within the industry is seen as preferential. Countries that still have colonial ties cannot achieve true independence if these linkages are not made. Additionally, for African persons traveling to the Caribbean, a deeper understanding of the tourism industry and the ways we unknowingly contribute to the degradation of Africana people needs to be had as well. Additionally scholarship within Africana studies must be produced that focus on this phenomena. For the most part scholars are located in Hospitality & Tourism Studies, Political Ecology, Environmental Studies, Cultural Studies and Anthropology. It is extremely problematic when Africana people in the Caribbean are continually referred to as ‘other,’ and when concepts such as ‘modernity’ are tied to travel (with travelers meaning white European and white American). Cultural transmission is still discussed in many works as going from center to margin - with Caribbean people being the margin. These are ideological problems that must be identified and corrected from and by African people. Africana Studies, in researching and writing about phenomena occurring wherever African people are present must be in these conversations. Archaic and racist constructs must not be present when we are understanding the tourism industry as it affects many Africana people in the Caribbean. For traveling Africana people making connections within the Diaspora, utilizing travel companies such as Travel Noire, African Diaspora Tourism, or organizations such as Afrocentricity International that frequently hold conventions within the African Diaspora is important in combatting the oppressive ways tourism functions. Continuation of concentration of ownership, infrastructure, access to natural resources and policing Africana culture and bodies by Western entities have all contributed to the pacification and false liberation of Africans in the Caribbean. Control of narratives, cultural practices and ownership on African terms is essential for the de-commodication of Caribbean countries and Caribbean peoples. Works Cited Baver, Sherrie L. and Barbara Deutsch Lynch. “The Political Ecology of Paradise.” Beyond Sun and Sand. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006. JSTOR. Web. 16 March 2015. Bennett, David and Sophie Gebhardt. “Global Tourism and Caribbean Culture.” Caribbean Quarterly, Vol 51, No. 1, March 2005: 15-24. 15 March 2015. Biney, Ama. “The Intellectual and Political Legacies of Kwame Nkrumah.” The Journal of Pan African Studies, Vol 4, No 10, January 1012: 127-142. 19 March 2015. Conway, Dennis. “Tourism, Agriculture, and the sustainability of terrestrial ecosystems in small islands” Island Tourism and Sustainable Development: Caribbean, Pacific and Mediterranean Experiences. Google books. Westport: Greenwood Publshing, 2002. Google Books. Web 20 March 2015. Daniel, Yvonne. “Tourism, Globalization, and Caribbean Dance.” Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2011. JSTOR. Web. 17 March 2015. Goodwin, James. “Sustainable Tourism Development in the Caribbean Islands Nation-States.” Michigan Journal of Public Affairs, Vol 5, 2008:1-16, March 2015. Miller, Marian A. L. “Paradise Sold. Paradise Lost: Jamaica’s Environment and Culture in the Tourism Marketplace” Beyond Sun and Sand. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006. JSTOR. Web. 15 March 2015. Williams, Tammy Ronique. “Tourism as Neo-colonial Phenomenon: Examining the Works of Patullo & Mullings.” Caribbean Quilt, Vol 2, 2012: 191-200. 14 March 2015.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed