|

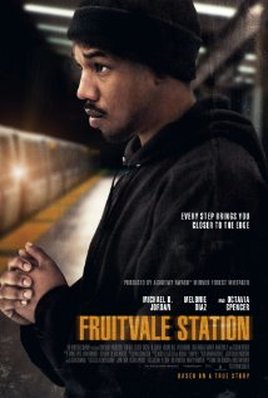

Written by Chris Roberts  Black life matters. I was 20 years old when Oscar Grant was shot in his back, unarmed with his face adjacent to the concrete. Concrete that to this day is marred with the hole from the bullet that pierced his skin. I did not know that in the following years I would come to live in Oakland, that I would come to live moments of my life in the same train station where Oscar Grant had his taken away. Extra-judicial killing of Black youth in the United States is nothing new, in fact, it is as American as the stars and stripes. The poignancy in Grant’s story is that it reminds us, being Black and breathing is often all the reason necessary for one to be deemed a threat to humanity. Ryan Coogler’s Frutivale Stationgrounds its audience in the humanity of Oscar Grant. Coogler lays the bricks of Grant’s dynamism throughout the film, cementing this work as a seminal piece of art in the discourse of Blackness in the 21st century. Right at the onset of the film, Coogler introduces us to Grant (played by Michael B. Jordan) in a way where we are privy to his struggles and flaws as a human being. This is important because within the first five minutes we see Oscar not as an idealistic, or cookie-cutter image of a Black man made digestible, but rather a representation him in his raw, unfiltered essence. Furthermore, this counteracts the U.S. centered narrative of connecting “mattering” to violence enacted upon Black lives only when the victim is a “perfect kid,” an “honors student,” or something of that nature. Coogler does not predicate Grant’s humanity on his assimilation into white society. Oscar as a Black man existed, therefore he was human, and therefore he mattered. The film takes place over the course of New Years Eve 2008, and the early hours of 2009, so in total it covers less than 24 hours. While watching I could not help but be reminded of the song by Mase, Black Rob, DMX, and The Lox 24 Hours to Live (1998). In this song, each of the artists ruminates on how they would spend their final hours, listing activities from the mundane to the essential. For example,“explain to my son and my girl that I love em” is one exuberant claim from DMX on this track. While reflecting on DMX’s words, I wonder what Oscar’s response would have been to the question “If you had 24 hours to live, just think, where would you go, what would you do, and who would you want to notify?” In the film, Coogler, though not answering the aforementioned question directly, does illustrate to the viewer those who Oscar cares most deeply for in his life. The three women that represent purpose and motivation to Oscar in the movie are his mother, his girlfriend, and his daughter. Each woman occupying a different corner of the room of Grant’s soul; where he stores his hopes and his dreams. His girlfriend Sophina though often frustrated and annoyed with Oscar, knew that he was genuine in his care for their family. His mother, though disappointed in her son’s struggles and short-sightedness, knew the potential in the young man she raised. His daughter, though sad that Daddy wasn’t already around, knew that she was the world in her father’s eyes, and that her happiness was crucial to him. In each of these spaces Oscar was different. As actor Michael B. Jordan states in an interview with Black Tree Media “Oscar was a different person to many of the people in his life, and all of those parts of him were true.” This revelation reminds the audience that Blackness is not a monolith, the humanity and existence of Black people is not isolated to the myopic perceptions rendered normal by white society. We come layered, flawed, awesome, and beautiful. And in Fruitvale Station, Coogler captures that dynamism exceptionally well. One of the things I appreciate most about Coogler’s construction (and Jordan’s portrayal) of Grant is that we see that he is a caring person. The scene where Grant cares for the dog that is struck by a car is a pivotal moment, there we see Grant express intense emotion for something that is not himself. By doing that, we are shown that “someone like Oscar” who stereotypically would be viewed as being selfish and inherently violent is actually, inherently loving. This reimagines Black men as not the perpetrators of violence, but as the lovers of life and existence. This expression of Oscar as loving is extended further when we see his interactions with his daughter, which I would argue are the most soul piercing moments of the film. Oscar loves his daughter without hesitation, without doubt, and without prompting. Not only is Oscar a present Black man in the life of his daughter. He, in this film, is an exceptional Black father. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Coogler states: “Film is a motif, How environments have an effect on characters. The BART station is an institutional environment, the hospital is an institutional environment, the store he works at is an institutional environment [the prison he’s in]. These institutional environments, although they’re there under the guise of helping people… For characters like Oscar, for people like Oscar, these institutional environments don’t help us, often times they harm us… that became a motif in the film. [Contrasting] seeing him in his domestic environments and these environments.” – Los Angeles Times Interview (2013) The directors use of institutional environment as a corollary for the ways that Black bodies experience institutional racism is genius. Larry Neal in 1968 wrote of Black art that it is “art that speaks directly to the needs and aspirations of Black America.” And by highlighting racial profiling, socioeconomic impression, and the brutality of the police state Coogler has his pulse on what Black people in the United States need to see today. “I want to make movies that I care about deeply.” That is what Coogler told Black Tree Media in an interview about this film. I would contend that not only Coogelr, but all Black people in the world should care deeply about this film. It is not just Oscar’s story, it is our story. In the closing moments of the film we see Tatiana, in real life, at an event in honor of her father. It is here, that Coogler depicts the convergence of the ancestral and the immediate that permeates Africana experiences. The scene begins with a shot of a crowd of community members huddled in an intimate space at BART. This tells the viewer that what we are witnessing was to be experienced by a collective, not an individual. Next, we see the pouring of water from a jug by an event participant, which is a direct exemplification of the African tradition of pouring libations. Libations create space and pathways for our ancestors to be acknowledged by, and join us, in the experience to come (in this case the event commemorating Oscar Grant). Culture is intertwined with how Black people heal, how we revere, and how we honor. The person who is holding Tatiana is also wearing a necklace with beads adorning it that are red, black, and green. Those colors are representative of the Pan-African flag designed in 1920 by the United Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, and speak to a cultural continuity and connection among people of African descent all over the world. Oscar’s daughter being Black and Mexican, constructing her own narrative of Blackness and identity, shows here that through culture that she can cultivate healing spaces. By capturing this moment, Coogler illustrates; healing that resonates is collective, and the traditions of Africana people are ripe for opportunities to empower both the individual, and the community.

0 Comments

|

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed