|

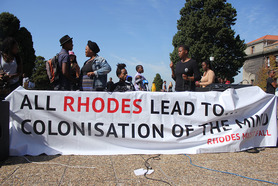

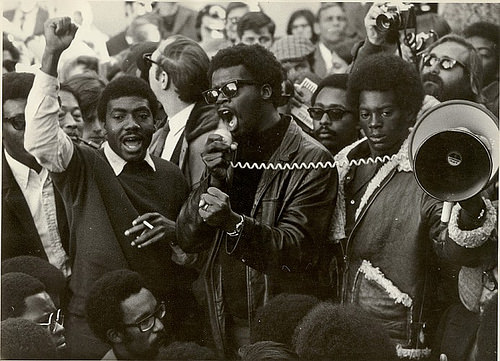

Written by Serie McDougal and Sureshi Jayawardene REVOLUTIONARY CONTAGION ACROSS CAMPUSES During slavery in 1851, Louisiana physician, Dr. Samuel Cartwright explained that some enslaved African people were suffering from a disease called drapetomania, which caused them to want to run away from white captivity (Cartwright, 1851). He explained that there were a preliminary set of symptoms of this illness and he called it incipient drapetomania. It included expressions of dissatisfaction with and resistance to White dominance. According to Cartwright (1851), slave owners needed to be aware of this pathology so they could stop it from spreading by administering the appropriate treatment, whipping. Today, a different contagion of self-determination is spreading across campuses in the U.S. Students at the University of Missouri have realized their power and are effectively using it to transform the racist climate at their school. This has spurred Black student-led political action on numerous campuses across the country. And like the White supremacists of the 1800s, conservatives, including presidential candidate Donald Trump, have attempted to pathologize them by calling their resistance to oppression “crazy.” Just last Friday, a conservative media source summarized some of these student demands as “nutty” and “disturbing,” while acknowledging that many of them are “reasonable things for black and minority students to be concerned about." AWAKENING THE GIANT Overrepresented in college athletics, African American students face stereotypes that cast doubt on their interests outside of sports on campuses (Bonner, 2014). In the fullness of time, the United States is only a few hundred years removed from forced displays of physicality such as slavers who forced enslaved Africans to engage in athletic competition with other enslaved Africans as a form of entertainment for whites (Roden, 2006). African people have used sports as a form of self-expression and physicality, a career path, a means of learning team work and discipline, a means of healthy competition and physical conditioning, and to pay for college education. However, abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote, as early as the 1800s, that Whites used sports to politically pacify Blacks and to prevent rebellion (Douglass and Garrison, 1846). Whites expected then, as many do today, that Black athletes be grateful entertainers who remain politically silent and submissive. The Back football players at Missouri acted in the revolutionary tradition of Black athletes such as Paul Robeson, Jim Brown, and Muhamad Ali who stood on the principles of self-determination, justice, Black community, and liberation. EVOKING THE BLACK CAMPUS MOVEMENT Further, the ongoing Black student protests on college campuses nationwide and subsequent demands to university administrators reflect the fervor of Black student protests during the Black Campus Movement of the 1960s. At that time, Black students called for similar shifts and commitments, in what Ibram Kendi (formerly Rogers) terms the “racial reconstitution of higher education” in America. Scholars have documented the Black Campus Movement in the 1960s and their highly generative outcomes such as a number of Black Studies departments and graduate programs which many of us are privileged to be housed in. Because of these achievements, Black students are exposed to more culturally relevant curricula as well as learning environments that require careful thought and research that can improve Black communities. But, if these gains were made, what accounts for Black student protests today? Their demands, too, are similar to those made in the late 1960s. Central to these demands at approximately 37 colleges and universities in the past few weeks are issues of racism and White supremacy amidst other isms and phobias. In a recent blog post for H-Afro-Am, an Africana Studies network of scholars, Kendi wrote, “Despite th[e] recent burst in books on the subject, we still have merely scratched the surfaced on this massive Black campus movement. We have yet to detail what happened on the vast majority of the more than 500 campuses in 49 states that Black student activists rocked towards diversifying from 1965 to 1972. Even at Mizzou, there is no major history on the BCM. The story of those amazing Legions of Black Collegians, founded in 1968, has yet to be told.” Additionally, we need to carefully examine the go-to rhetoric of diversity and inclusion that universities tout as a quick response intended to quell student unrest. We need to parse out the symbolic gestures from real efforts that actually meet student demands. Amer Ahmed recently penned, “these same institutions maintain their rhetoric about diversity and inclusion in superficial ways attempting to do little as possible without truly having to change.”  #RhodesMustFall Photo source: thedailyvox.co.za #RhodesMustFall Photo source: thedailyvox.co.za THE GLOBAL BEAST: WHITE SUPREMACY For Black students confronted with the effects of everyday forms of racism as well as more structural racist impediments to their wellbeing and learning, universities are proving to be a site of contestation beyond the United States. In early October this year, a crowd of 2,000 Black students at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa shut down the university just prior to the start of exams. The campus has remained closed since. They protested the cost of higher education for poor Black students who are struggling to remain enrolled in the university, as well as the university’s and government’s inadequate efforts to ameliorate these costs. In the spring, Black students at the University of Cape Town demonstrated to have the bronze statue of British colonial administrator, Cecil Rhodes, removed from its central position on campus. Their determined efforts led to international attention through a social media campaign tagged #RhodesMustFall. Students stressed that the statute was not merely something that caused discomfort, but the ultimate symbol of institutionalized racism at the university. They demanded the Executive Council—the highest authoritative body at the university—remove the problematic Rhodes figure, but also take seriously the deeply entrenched racist values and norms. This was soon followed by #FeesMustFall, and the students won their demand of a 0% increase in tuition fees. In September, Black students at the University of Nairobi protested against delayed Higher Education Loans Board (HELB) loans which prevented their continued enrollment. Similar to demands for transformative change at US institutions of higher education, students on the African continent are also seeking “decolonization,” “transformation,” and ultimately a “racial reconstitution” for improved and culturally sensitive learning environments and opportunities. Certainly, the declared solidarity between #RhodesMustFall, #BlackLivesMatter, #ConcernedStudent1950, and similar campaigns that lend themselves to themes of diasporic spirit and Pan African politics. What we are also witnessing in an unprecedented way is the degree to which the roots and severity of institutional assaults on Black life and learning are plaguing the African world. Works Cited Bonner, F.(Ed.) (2014). Building on resilience. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publications. Cartwright, S.A. (1851). Report on the diseases and physical peculiarities of the Negro race. The New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal, May, pp. 691–715. Douglass, F., & Garrison, W. L. (1846). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass: An American slave. Wortley, near Leeds: Printed by J. Barker. Roden, W. (2006). Forty million dollar slaves. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. Rogers, I. (2012). The Black campus movement: Black students and the racial reconstitution of higher education, 1965-1972. New York: Palgrave.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed