|

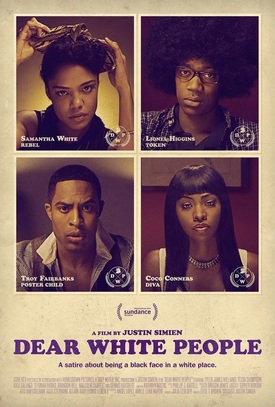

Written by Chris Roberts  “Black Culture Still Missing” On October 17th, the film Dear White People (DWP), directed by emerging filmmaker Justin Simien, who happens to be Black, debuted in 11 theaters. To date, DWP has grossed over 2 million nationwide, and shows no signs of losing steam at the box office. DWP is hailed by critics as “a young Black filmmaker[s] update to Spike Lee’s School Daze and Bamboozled”, “a Do The Right Thing for Gen-Y” and a “must see” in the wake of the murders of Mike Brown, Renisha McBride, and other Black youth. Even per Shadow and Act On Cinema from the African Diaspora, one of the largest online cinema platforms for Africana people: “with biting humor that never loses its teeth, Dear White People may very well be the public address we all need.” In spite of such adulation from a wide array of interlocutors, it is imperative that as Africana (Black, of African descent, Continental and/or Diasporic African) people who are concerned with the liberation of Africana people from White supremacy we analyze for ourselves what DWP is, and what it is not. Though littered with occasionally suitable ruminations on “being/becoming” a Black person whilst confronted with microaggressions in a society dominated by White heteropatriarchal normativity, there is little to Simien’s critique of Whiteness beyond the metaphoric wagging of the finger at unseemly at times, yet ultimately redemptive White individuals. Justin Simien does not purport that his film is a treatise on racism; to the contrary, he says, “it is about identity, it is identity in a world where covert racism and microaggressions occur.” However, if Simien imagines himself in the same satirical conversation as Spike Lee and Melvin Van Peebles, he should be aware that a reduction of White supremacy to “covert racism” and “microaggressions” is disrespectful to the tradition he fancies this work following. In DWP, Sam White, the Black Student Union leader, proclaims boisterously to her peers that Black culture is missing and the objective of her push for influence on campus is to “Bring Black Back to Winchester.” However, what is missing throughout the film is any discussion of what exactly that “missing Black culture” is. Is there an infringement on the political autonomy of Black students to speak on Pan-African issues (School Daze)? No. Is there pressure to discontinue reverence for Black community activist organizations and ideals (Higher Learning)? No. What beyond a numerical decrease in Black bodies is there that reflects a “missing Black culture?” Virtually nothing. In the film, the “epicenter” of Black culture is the dining hall, wherein according to Sam “everything from Kanye West to theoretical relativism” is discussed, telling the viewer nothing about “Black culture” aside from two assumed divergent topics. Aptly, the only cultural product that is referenced with any consistency in the film is food, particularly fried chicken, waffles, as well as macaroni and cheese. In his effort to be diverse and dynamic in his portrayal of Blackness, and not define anything, Simien in post-modernist style divorced his discourse on Black culture from any ancestral roots or cultural traditions of Africana people. Culture is more than topical interests and “better snacks” it is better understood as “shared perceptions, attitudes, and presdisposition that allow people to organize experiences in a certain way” (Asante, 1990, p.9). Hence culture is not merely something to be performed and “worn” but rather something to be rooted and centered in. This choice by Simien to uproot his characters from any Africana cultural foundation casts them hopelessly into the wind of Whiteness. Thus, leaving his characters looking for themselves through the cultural lens of their oppressors, and relegating their “fight” for “Black culture” to little more than an expediting of the assimilation process. Justin Simien defines DWP as a satirical work. However, though that is true, when looked at in the Africana cultural satirical tradition, it becomes clear that the film is drenched in Eurocentric epistemological assumptions and preoccupations. In other words, the film is so enamored with humanizing white people, that it does a disservice to anything emancipatory for Black people. According to West African writer Kimani Njogu, satire is best understood as “militant irony… aggression constitutes satire’s indispensable component, satire is an attack.” What is it that Simien is attacking? He has stated: “I didn’t want to vilify anyone in the film… [the white students who often throw Blackface parties] they didn’t realize how messed up this was.” With this sort of accommodationist view, Simien’s work is more sympathetic apology than aggressive attack. In African American Satire: The Sacredly Profane Novel Daryl Dickson Carr writes of African American satire that it “frequently presents… absurd, obscene milieux that reveal racism as the rotten but definitive core of American cultural politics. The satiric novel repeatedly installs, subverts, then reinstalls racism as the agent of ideological and political irrationality and chaos…” Instead, what one sees in Simien’s work is a removal of racism as the core, never to be reinstalled, but substituted for the more convenient and supposedly racially indifferent problem of capitalism and economic profit incentive, of which people of all racial groups are again, supposedly equally complicit. This idea of “equal complicity” is where Simien’s work falls woefully short. In Do The Right Thing (1989), the police state is the chief perpetrator of racism. In School Daze (1988), intra-racial solidarity is the clear pathway, to “waking up” and recognizing the real enemy, white supremacy (cast in this work as the Apartheid regime in South Africa). In Bamboozled (2000), there is no shortage of Black people complicit in their own oppression. However, Lee calls out the contribution of these conspirators to the decimation of Black people and Black culture, and the collaborator is made to confront his/her decision. In the end, these contributors are not cast as the ventriloquist in their own puppetry, merely puppets that are caught in the tangled web of strings that is white supremacy. In the Africana satirical tradition, Niyi Akibgbe, in the article Speaking Denunciation: satire as confrontation language in contemporary Nigerian poetry (2014) wrote, "satire is expressed using proverbs, aphorism and irony which serve as artistic elements that are grounded in African tradition and culture, satire in short allows the poet to air social criticism and express social engagement.” Devoid of any concrete satirical commentary on the utility of culture for Black people, Dear White People is indeed itself “missing Black culture." Though it is true that there are always co-conspirators and collaborators when any group is oppressed on a macro-level (Jews and Nazi’s, Native Americans and Europeans, Africans and Europeans, etc.). But, to pretend as if Black people have constructed and continue the parameters in our own oppression, in our own genocide, in our own Maafa, is akin to claiming it was African people who built the slave ships upon which we were loaded, in the conclusive analysis the Europeans built those ships, made those shackles, and carried out the work of enslaving and massacring millions of African people and no amount of “complicity” changes that truth. Yet in Simien’s film, the potential orchestrators of the Blackface party are Coco and Sam. Simien invokes Lee Daniels’ myopic bastardization of Black Power in The Butler in his portrayal of Reggie, the “pseudo-Black nationalist” supporter of Sam in DWP. By his own admission, Simien crafted Reggie to be one-dimensional. Reggie is not posited as either comforting or understanding, or pushing Sam to use her passion to push through a sensitive time. Instead, he is consistently insensitive and selfish, fulfilling the stereotype of the Black male that marginalizes Black women, ultimately unworthy of the commitment of a Black woman. When Sam leaves due to her father’s health without providing her friends an explanation, Reggie and the other Black students’ concern for her is never positioned as friends wanting to see if she’s ok, or help her through a difficult time. They are solely shown as a group that wants to utilize her for their own interest, while Gabe is the caring, comedic, and understanding shoulder to lean on. Reggie sees Sam’s leadership position as an opportunity for the group. When Reggie told Sam “Forgive me if I see something in you, something folks like me can get behind” that could have been a catalyst for a healthy and affirming relationship (friend or otherwise) between Sam and Reggie. Instead, nothing came from this discussion. Nothing except for Sam being filled with grief that Gabe found out she kissed Reggie, for which she later apologized to Gabe. The obsession with the White gaze for Simien becomes most clear when in interviews he states that he researched the reactions of white people after Blackface parties, however, in the movie there is no attention or time given to the voices that Black Student Unions around the country have raised in regards to these parties and how they feel in these oppressive spaces. But, due to the fact that the Winchester BSU in the film did not issue any statement, push for any enhanced study of their culture and community via Africana Studies, or stage any direct action in response to the Blackface party that is in the tradition of multiple Ivy League institutions such a large oversight cannot be seen as much of a surprise. But such a large oversight cannot be seen as much of a surprise, the agency of Black people as a collective was of little to no concern in Simien’s project. Sam, the archetypal tragic mulatto, finds the solution to her "confused" identity in her love for White people, particularly her white male Teaching Assistant Gabe. In resolving Sam’s dilemma of identity in this way, Simien is fueling the anti-Black and Anti-African thrust in contemporary U.S. society. Frantz Fanon, captures Sam’s acceptance of her lost desire to be a leader for the Black community poignantly when he wrote in his classic work Black Skin White Masks (1952) of a Black Martinican woman “… unable to blacken or negrify the world, she endeavors to whiten it in her body and mind.” When Sam is removing her head wrap and her jewelry, in the scene before the Blackface party, she is literally discarding her Blackness, and solidarity with the Black community. It is now, after Sam has "come to her senses" about being the girl whose “favorite director is Bergman but [tells] people its Spike Lee” that Gabe and she can be together. In the mind of Sam it is, as Fanon says, “The day the [W]hite man confessed his love for the mulatto girl, something extraordinary must have happened. There was recognition, and acceptance into a community that seemed impenetrable… Overnight the mulatto girl had gone from rank of slave to that of master” (Fanon, 1952, p. 40). And in Sam’s own words, she went from “rebellion on the plantation” to apologizing to Gabe saying: “how can I do that [not love you and leave them] to anyone I love.” Sam was indeed “tired of being everyone’s Angry Black chick” as she told Lionel, and in the arms of the White savior she found inner peace, to quote Fanon, “Gone was the psychological debasement [of being mulatto]… She was entering the white world." University of West Indies scholar Carolyn Cooper illuminates this brand of internalized racism in her article No Matter Where You Come From: Pan-Africanist Consciousness in Caribbean Popular Culture when she wrote: “these new tragic mulattoes [are] victims of an old fashioned Euro-American racism that masquerades as newly fashioned cultural theory, derace, and erase themselves.” Simien’s casting of Black identity as unable or unwilling to have space for Sam is nothing short of erasing her Blackness and replacing it with whiteness. In totality, the film Dear White People is a diluted satirical foray in surface level identity politics that massages the White consciousness. That said, the film is stocked with talented Black actors who all have promising professional futures ahead of them. Additionally, the film has witty dialogue far beyond the coonery of Tyler Perry and others, as well as solid Black professionals in front of and behind the cameras. Nevertheless, the film provides White people with scapegoat “good White folk” to visualize themselves as in the film, thus escorting them from the party of those they see as white supremacist benefactors. This individual scapegoating of systemic oppression was not in School Daze (1988) or Bamboozled (2000), two films which either Simien himself, or via multiple critics, have cited DWP as being in the vein of. Black women are cast as silent, confused, and/or unworthy in the eyes of Black people. And Black men are cast as verbose, sheepish, insensitive, and/or unworthy in the eyes of Black people. In the Africana cultural satirical tradition satire must attack, it must be scathing and leave the audience, especially the White audience, deeply disturbed and exposed for their complicit nature in the maintenance of White supremacy. Instead, if anyone is being corrected through what Ngugi wa Thiong’o calls the painful and sometimes malicious laughter of satire by Simien it is Black people, for not being more understanding of and loving toward White people, because they don’t know how what they’re doing is messed up. Simien casts his Black woman lead character as positive in her reaching Eurocentric Fanonian conclusions that “I will not make myself the [man or woman] of any past. I do not want to sing the past to the detriment of my future… I am my own foundation” (Fanon, 1952, p.204). This is indicative of “Black culture” as Simien has constructed at Winchester when one looks at Black relationships, on both intimate and friend levels. Arguably, the best scene in the movie is the interaction between Coco and Troy after they’ve had sex, both sharing and critiquing their desires for fame and inclusion. It is here we see one of the rare moments of listening and support between Black characters. Yet Troy ultimately is unable to commit himself to Coco, a Black woman, proving to be the same self-serving Black guy who "espouses white culture, white beauty, and whiteness.” For Troy, he is his own foundation, he thinks he doesn’t need what Coco has to offer, and he has adopted the Fanonian individualistic solution to racism. The same goes for Sam, now nestled firmly in White acceptance, she will no longer “sing the past” which here are her Black friends and her commitment to Black people, for doing that now would be to the “detriment of [her] future” with Gabe in white society. In the words of John Oliver Killens: “Integration comes after liberation. A slave cannot integrate with his [her] master.” So the real question is, Dear Black People, are we free yet? WORKS CITED Asante, M.K. (1990). Kemet, Afrocentricity, and knowledge. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press. Akingbe, N. (2014). Speaking denunciation: satire as confrontation language in contemporary Nigerian poetry. Nigeria: Afrika Focus. Cooper, C. (2011). Where You Come From: Pan-Africanist Consciousness in Caribbean Popular Culture. College of the Bahamas. Dickson-Carr, D. (2001). African American satire: the sacredly profane novel. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. Fanon, F. (1952). Black Skin White Masks. France: Editions du Seuil. Wa Thiong’o, N. (1972). Homecoming. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed