|

Written by Serie McDougal III & Sureshi M. Jayawardene

According to a Moroccan proverb, endurance pierces marble. With a deep well of inspiration and drive, Justice Brown Jackson drew motivation from her family to achieve and endure many of the very same barriers as other Black people and working Black women in particular. Yet she persisted. She has emerged as a national model of motivation, discipline, persistence, endurance, and success. She is in many ways the embodiment of that Moroccan proverb. But what is the practical meaning of Judge Brown Jackson for the ongoing movement to advance the African/Black world? How does her judicial methodology relate to Black people? What can we expect from a Black woman with the ability to influence the direction of an entire country? In her confirmation hearings, when pressed for her judicial philosophy–especially at the hands of Republicans in Congress with their vile and brutal lines of questioning and overtly double standards–Justice Brown Jackson pointed to a perspective on legal analysis in favor of a particular perspective on the law. She underscored how her “judicial methodology” could be identified in how she approached judging. The tools she relies on to reach her decisions are consistent and clear in her rulings and sentencing record: focused attention on the details of the cases and claims therein; a keen analytical mind; careful reading of statutes and precedent; reference to law dictionaries when meanings are in dispute; and a deep sense of respect for procedural requirements that limit judicial authority. Justice Brown Jackson has a record that involves a few very significant moments and rulings—for example, her focus on reducing unwarranted sentencing; the amicus brief she wrote defending a Massachusetts law against abortion protesters at clinics; her demonstrated willingness to challenge presidential power and corruption, as evidenced by her Trump-era ruling compelling President Trump’s counsel to testify; her history of siding with unions, as she did when she worked to protect federal employees from firing; and her siding with the Centers for Disease Control’s eviction moratorium early during the COVID-19 pandemic. Each of these rulings, positions, and opinions from Justice Brown Jackson falls on the side of the majority of African American political attitudes, which lean pro-choice, pro-affordable/accessible housing reform, pro-sentencing reform, and pro-union (McLaughlin, 2022). Then, there is her sentencing record. From John Punch to Thomas Brown Jr. The legacy of freedom for Black people has involved the use of law as an instrument of justice and an instrument of systemic violence, racist exploitation, and other forms of injustice. Bias in sentencing in North America can be traced back to the earliest American colonies and the treatment of people like John Punch. In 1640, a Black man named Emmanuel and six White men were caught trying to escape from their indentured servitude. All had extra time added to their term of indentured service, but Emmanuel alone was beaten, branded, and shackled for 12 months. In a similar situation, a Black man named John Punch along with two White men were caught trying to run away. The White men were given an extra few years added to their period of service, and John Punch was sentenced to bondage for life. It is not uncommon for judges to be influenced by their personal beliefs and values. The manifesting results can vary, however. A judge’s political, religious, or other positions can lead them to approach a case with a desired outcome in mind and thus, find a reasoning that supports that outcome. But this isn’t always the case. Judge Brown Jackson’s record clearly contradicts Republican lawmakers’ claims that her holdings are driven by liberal biases rather than the law. The legacy of Punch and others remains an enduring presence in the American criminal justice system; a prime example is Justice Brown Jackson’s uncle Thomas Brown Jr. (Marimow & Davis, 2022). He was sentenced to life under a three-strikes law. Eventually, due in large part to her own prominence, her uncle’s sentence was commuted by President Obama. Equity in sentencing is not an abstract legal topic for Justice Brown Jackson; it is personal. Moreover, a significant part of her judicial methodology is her insistence on fairness in sentencing and her refusal to look at incarceration as the sole instrument of criminal punishment and deterrence. Significance in Symbolism Black political leadership involves symbolism and practical value. There’s considerable debate about the value of representation, especially when the people that achieve high (and historic) status and positions have questionable track records. Yet symbolism is still important. A long-held concern in Black communities is the gradual impact of negative images of Black women and the subsequent effects of such imagery on how Black women view themselves as well as how others perceive them. However, alternative perspectives (like the Drench Hypothesis) tell us that just a few powerful images of Black women (like Michelle Obama) have the power to drown out the noise of mainstream portrayals of Black women that present them as hyper-sexualized, angry, strong, and caretakers. Justice Brown Jackson’s rise to the Supreme Court–as well as her entire career to this point–challenges the Black community to equip our children with empowering messages about themselves and their possibilities as African people; how to cope with attacks on their personhood as Black people; and how to interpret and appraise images of Black women (Adams-Bass et al., 2014). Justice Brown Jackson’s ascendance also presents Black communities with the challenge of providing awareness and appreciation of her trajectory. Her upbringing, her parents, their lives and careers, the family’s commitments to public education and HBCUs, her work as a public defender and trial judge, her work on the Sentencing Commission, as well as her many other accomplishments speak volumes to the pathways she created, discovered, and pursued as someone with a fairly regular life and background. These are images and stories that Black children across the nation can draw inspiration and motivation from. Justice Brown Jackson’s life and career offer Black youth a real life example, meaning, and symbolism for the Moroccan proverb, endurance pierces marble. Furthermore, Judge Brown Jackson’s ascendance presents Black communities with the challenge of remaining active through all means of political advocacy—from electoral politics to grassroots activism to advocacy for reform on upcoming issues that will be decided by the Supreme Court in the near future, including hot-button issues like abortion and gun control. References Adams-Bass, V., Bentley-Edwards, K. L., & Stevenson, H. C. (2014). That’s not me I see on TV. . . : African American youth interpret media images of Black females. Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 2(1), 79–100. https://doi.org/10.5406/womgenfamcol.2.1.0079 Howe, Amy. “Profile of a potential nominee: Ketanji Brown Jackson.” SCOTUSblog (blog), February 1, 2022, https://www.scotusblog.com/2022/02/profile-of-a-potential-nominee-ketanji-brown-jackson/ Marimow, A. E., & Davis, A. C. (2022). Stark life experience could set one court hopeful apart. Washington Post. McLaughlin, D. (2022). Judging Jackson. National Review, 74(5), 10–11.

1 Comment

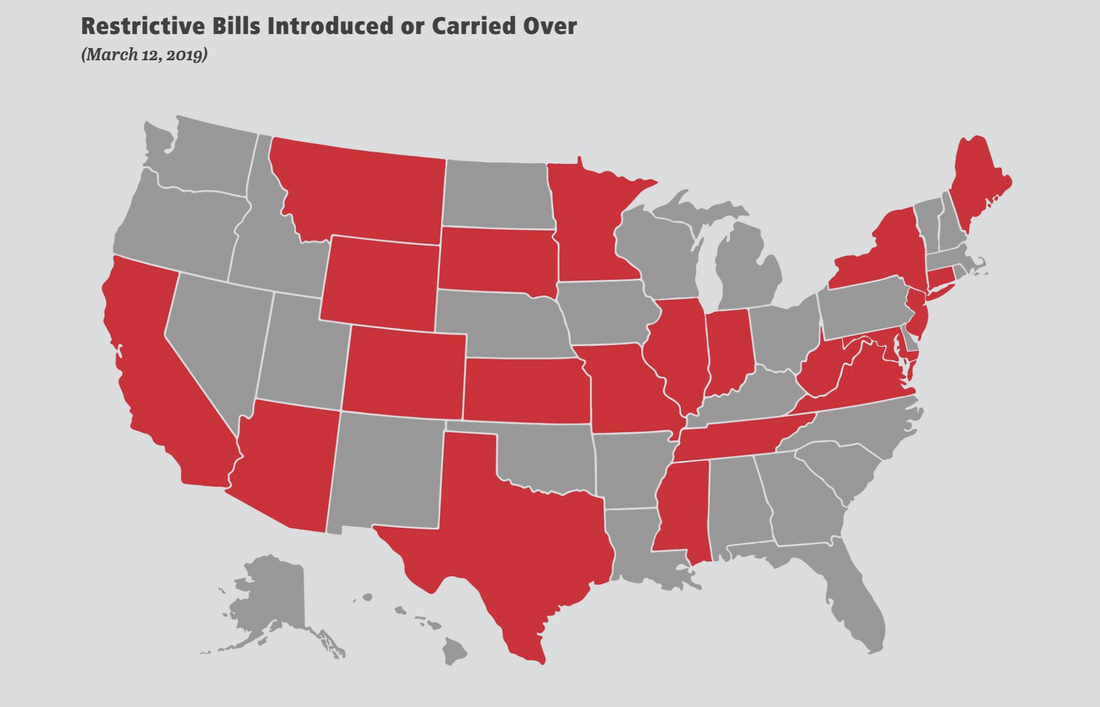

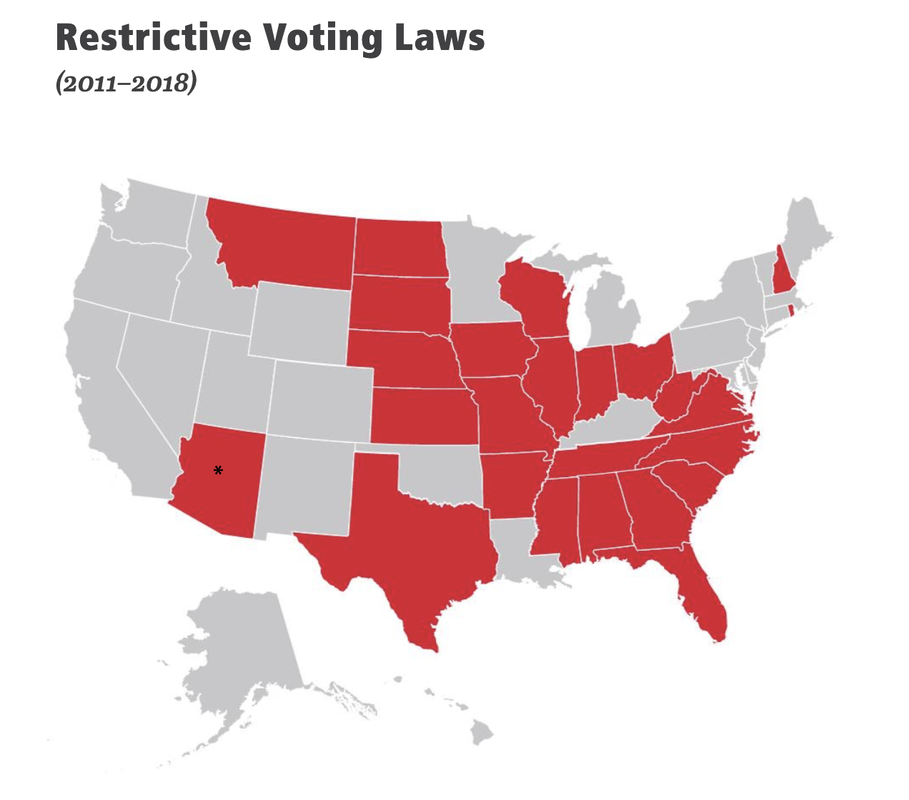

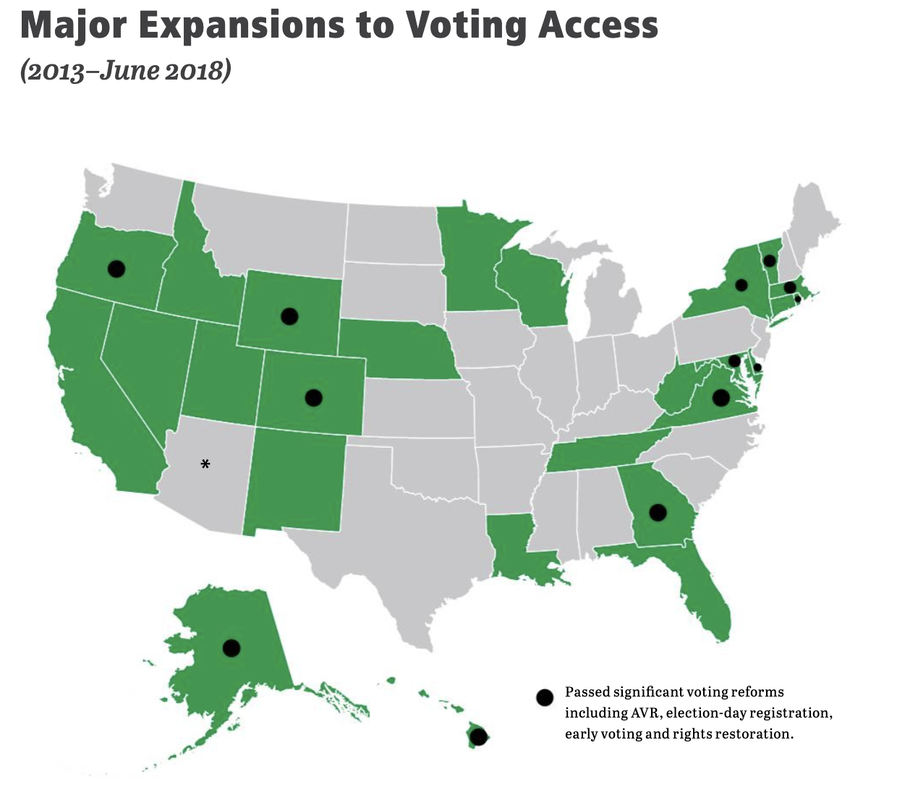

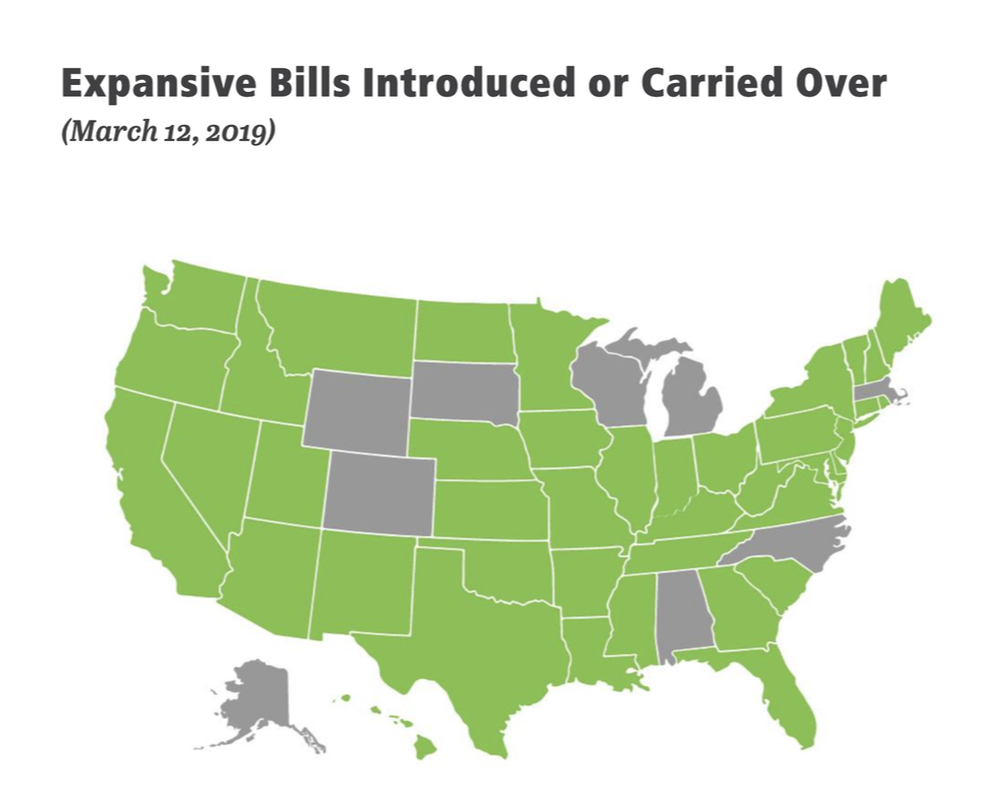

Voting Rights in 2019: Summarizing the National Urban League’s 2019 State of Black America Report6/12/2019 Written by Sureshi Jayawardene and Serie McDougal, III The National Urban League’s (NUL) State of Black America report is the most comprehensive annual assessment of Black life in the U.S. The 2019 report, Getting 2 Equal: United Not Divided, the product of a partnership between the NUL and the Brennan Center for Justice, focuses on the suppression, expansion, and protection of the vote for Black and Latino communities. A variety of authors with diverse areas of expertise, including scholars, nonprofit leaders, Urban Leaguers, politicians, and corporate frontrunners, identify current mechanisms of voter suppression within a genealogy of the history of the vote. Using an easy-to-read illustrative timeline, the NUL presents significant wins in the right to vote. While several of these key decisions point to the wider racist and exclusionary policies disproportionately and inequitably targeting anyone who was not White or male, five of these stand out in regard to African Americans: 1) 1870: the 15th Amendment granting African American men the right to vote; 2) 1920: the 19th Amendment guaranteeing Black and White women the right to vote; 3) 1965: the passage of the Voting Rights Act under Lyndon B. Johnson banning discrimination on the basis of race and non-English-speaking status in voting practices; 4) 1971: the 26th Amendment lowering the voting age to 18; and 5) 2019: the passage of the For the People Act (H.R.1) by the House of Representatives addressing issues of voter election integrity, election security, political spending, and ethics across all three branches of government. The above timeline points to necessary and important strides toward a more equal and equitable nation and society, but the enormous time gaps between each major constitutional and legislative achievement also underscore how much further the US has to go to secure the constitutional rights of all of its citizens. The NUL accurately presents the current mechanisms of voter suppression as the continuation of a long tradition of targeting people of African descent with efforts to suppress their political voices and subsequently limiting their power. One of the biggest tools of voter suppression today is the use of digital means in foreign election interference. For example, the authors explain that before, during, and after the 2016 presidential election, a Russian troll factory used digital espionage to exploit political and racial tensions and manipulate Black votes by creating fake social media identities and hijacking the missions of contemporary Black social movements like Black Lives Matter. A Senate investigation into Russian election interference found that African Americans were specifically and deliberately targeted through tactics that included posing as legitimate activist groups, spreading disinformation, and deteriorating trust in democratic institutions. As 2020—a pivotal election and census year—approaches, some authors in the report raise concerns about the persistent problem of census undercounts, which traditionally and disproportionately impact Black communities, limiting their access to federal resources. A more precise issue related to census undercounts is political gerrymandering, which continues to be used as a tool to limit the voting power of Black communities. However, in an effort to address a rarely highlighted problem, several authors in this report emphasize the role of prison gerrymandering. This is a more sinister method of manipulating electoral constituency and further exploiting an already hyper-exploited group toward ends that often do not even benefit the prisoners. The report explains that Black people are overrepresented at between 30-40% of the nation’s prison population, yet they are counted as members of the often rural and predominantly White communities where prisons are located, instead of the communities where they lived before being incarcerated. Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, succinctly articulates the severity and perverseness of the current attacks on voting rights for African Americans in this way: “Our rights are under attack by forces that are clever, sinister, diabolical, and intentional; and their allies run for the Supreme Court of the United States, to state legislatures all across the nation and around the globe, to allies inside the Russian Federation.” While some recent policies and bills have included necessary expansions to voting rights in certain states, others have been more regressive and thus resulted in further restrictions to the vote. The map below (from the Brennan Center for Justice) shows states where the vote is being threatened as a result of the introduction or carry-over of restrictive bills. According to the report, the past 10 years saw the enactment of a wave of laws restricting access to voting. This means that, since Obama’s election in 2008 when the Black voting rate matched or exceeded the White rate for the first time in U.S. history, states have taken significant steps to hamper African American access to voting, diminish their political voice, and undermine their constitutional rights. The National Urban League reports that, during the 2018 elections, voters in 23 states (approximately half of the country) faced harsher restrictions than they did in 2010. Additional restrictions have been passed since then. Despite these deliberate restrictions, ongoing litigation challenging voting restrictions can be found in Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wisconsin. There are also several states that have expanded their voting process in the past five years alone (see map below). There are also many states that have seen the carry-over or introduction of more expansive bills, such as those focusing on access to early and absentee voting, modernizing the voter registration process, and restoring voting rights to those who lost them due to felony conviction. The map below (also from the Brennan Center for Justice) shows the popularity of such legislative efforts across the states: As these maps show, several states with restrictive bills/policies have also instituted efforts to pass more expansive policies. This data is current as of March 2019, according to the report.

The 2019 report offers several solutions by way of policy recommendations highlighting efforts either proposed or underway under the leadership of Black politicians, community organizers, private industry, and the Urban League itself. These include, but are not limited to:

Written by Serie McDougal III

“The dark hour is the hour when you apparently seem to be losing out, yet you have courage enough to fight on until victory comes your way” (Garvey, 1921). Both Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey shared messages of critique and encouragement for Black leadership. They seem to center around the notion of courage. The language of leadership is in high use at the present moment. The midterm elections are upon us and the voices of our ancestors echo in our ears, or… perhaps they should be echoing. Talk of African American/Black voters holding the balance of power has shaped the current narrative. Not only as voters, but African American candidates have the potential of gaining seats across the country. African Americans are encouraged to be aware of and vote for Black candidates. In light of this current momentum, this short article is meant to recall the voices of Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X, on the pitfalls of Black leadership. Why be reflective now? We are 50 years past the Kerner Commission Report, the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and the founding of Africana Studies. Now is the time to reflect. Garvey and X’s critiques of Black leadership during their own times inform what Black people should be wary of in the present. Marcus Garvey argued persistently that Black leaders must unapologetically represent the true sentiments of Black people (Garvey, 1921). One of his ongoing critiques of Black leadership was what he identified as a tendency to abandon the interests of Black people when the hour is dark or under pressure from White people. According to Garvey most great victories are won at the turning point of the darkest hour. This turning point for Garvey is when the hour is dark and you seem to be losing out, yet you fight on until victory is won. It is at this point that Garvey warns that Black leadership too often abandons the goals of Black populations and begin to follow the paths being paved by those in positions of relatively greater power and privilege. The conditions of the masses of Black people in the U.S., for Garvey, was more the fault of false Black leaders than it was the masses of Black people themselves. Outside of electoral domestic politics, Garvey encouraged Black people to form organizations that look out for the interests of the masses of Black people. Like Garvey, Malcolm X also critiqued Black people who have been granted privilege in society and are groomed, publicized and promoted as spokespersons for the Black community as a whole. These Black people are then used against Black people who are struggling for liberation or revolution. More, specifically, he argues that Whites with resources use their money to influence Negro leaders to alter their agendas and compromise the ambitions of Black people. In fact, Malcolm X challenged the notion that they were African American or Black leaders at all, which is why he called them “Negro” leaders. Another one of his critiques was that Negro leaders had the tendency to create a narrative that depicts Black people as satisfied while they are suffering from oppression. It is their job to make everyone else feel that things for Black people are not as bad as they seem and that Black people are willing to be patient and long-suffering. Instead, Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X advocated for true Black leaders emerge from the masses to form organizations that represent the true interests of Black people, be courageous and uncompromising in their advocacy, and future-oriented in their thinking about Black liberation. Their ideas should continue to be criteria by which we evaluate Black leadership, and principles to ground the development of emerging Black leadership. Garvey, M. (1921). Leadership. In B. Blaisdell, Selected writings and speeches of Marcus Garvey. Courier Corporation, (p. 37-44). Garvey, M. (1921). Unemployment. In B. Blaisdell, Selected writings and speeches of Marcus Garvey. Courier Corporation, (p. 24-37). Malcolm, X. (1963). Message to the grassroots. In G. Breitman, Malcolm X speaks: Selected speeches and statements. Grove Press, (p. 3-17). Malcolm, X. (1963). At the audubon. In G. Breitman, Malcolm X speaks: Selected speeches and statements. Grove Press, (p. 88-104). Written by Sureshi Jayawardene

The misuse and addiction to opioids in the US has gained extraordinary attention since President Trump took office last year. In October 2017, the president declared opioid abuse a public health emergency, and Black communities nationwide rose with contempt arguing that structural racism was at the heart of the public motivation to address this issue. This outrage contrasted the nation’s response to the “crack epidemic” of the 1980s. This was a time when urban Black communities were stereotyped as portraying the “crack epidemic,” and the public approach to this crisis was different. Back then, when drug abuse was a “Black problem,” Americans showed little compassion to African Americans battling crack addictions. The media shamed Black mothers with addiction. The national response to drug abuse in the 1980s drew attention to the criminally dangerous drug addict. The media sensationalized the harm caused by crack abuse and “brought us endless images of thin, black, ravaged bodies, always with desperate, dried lips. We learned the words crack baby.” The “crack epidemic” was cast as a pathology of Black communities and the American public viewed this as evidence of African Americans’ collective moral failure. The national rhetoric was that Black people would have to “pull themselves out of the crack epidemic” and could only be allayed by “cordoning off the wreckage with militarized policing.” The nation responded with punitive measures codified in the “War on Drugs” and the public was “warned of super predators, young, faceless black men wearing bandanas and sagging jeans.” The resulting harsh sentencing and mandatory minimums continue to disproportionately affect African American and other communities of color with devastating effects on the incarcerated, their families and children. The invocation of “war” is absent with the current opioid crisis. Instead, the nation is linking arms to save lives and ramp up rehab initiatives. According to Ekow Yankah, a professor at NYUs Cardozo School of Law, the rallying cries this time around have been issued by various social actors including senators, CEOs, Midwestern pharmacies, and tough-on-crime Republicans who are trying to do something for the real people crippled by opioid addiction. The issue itself has been framed as a problem affecting young, suburban, and rural Whites. Contrary to this popular view, the Research and Policy Center at the Chicago Urban League (CUL) argued, in November 2017, that “this is a wholly inaccurate depiction.” According to the CUL, this predominant “Whitewashed” account eschews the profound effects of the opioid epidemic on communities of color. For instance,

While the public health approach to the opioid crisis is a significant step, as the CUL notes, treatment capacity must necessarily meet treatment needs. Thus far, this has not been the case for Chicago or the state of Illinois. The CUL insists, “African American people, families and communities should not be excluded from narratives told about the opioid epidemic. African Americans must be included in the development and implementation of national and local public health initiatives, as well as in treatment response plans.” Especially since the “War on Drugs” model toward drug addiction is alive and well in Chicago, the CUL urges a public health model that, first and foremost, is evidence-based and therefore, scientifically proven to work. To this end, the CUL identifies three types of intervention:

Added to the above multi-layered and evidence-based approach to addressing opioid epidemic, is the need to consider cultural variables in prevention strategies and programs. Not only is a certain respect for cultural traditions, values, and beliefs important in prevention programs. They also require protective factors such as religious and church activity, employment, family support systems, education, racial pride, and communal orientations. Steinka-Fry et al. (2017) determined that culturally sensitive treatments were associated with notably larger reductions in post-treatment substance use levels relative to their comparison conditions in their meta-analyses of experimental and quasi-experimental treatment programs. Current strategies devised to respond to the opioid abuse and fatalities in Africana communities throughout the US must necessarily ensure culture is central to these efforts to enhance the effectiveness of evidence-based programs. Works Cited Steinka-Fry, K., Tanner-Smith, E.E., Dakof, G.A., and Henderson, C. (2017). Culturally Sensitive Substance Use Treatment for Racial/Ethnic Minority Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 75: 22-37. Written by Serie McDougal and Sureshi Jayawardene

In the past month or so, there has been increased attention brought to the ongoing practice of the enslavement and trafficking of Black African migrants in Libya. Libyan ‘slave markets’ are not a new phenomenon, however. The International Organization for Migration, the UNs migration agency, reported in April this year that North African migrant routes were rife with ‘slave markets’ where “hundreds of young African men bound for Libya” were subject to treacherous conditions. For Black African migrants and refugees trying to reach Europe by sea, Libya is the main transit point. Many of them, from countries like Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal, face rape, torture, starvation, disease, and murder. Since the ouster of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has struggled to implement the rule of law and descended into civil war and lawlessness. Given this unstable political climate, Libyans see the slave trade as a lucrative industry. TIME reports some important figures for the dangers facing Black African refugees and migrants in Libya:

As a Pan-African community, this is a time for a multilayered response to the situation of our people in Libya. We commend the US foreign policy efforts advanced just this week by Congresswoman Karen Bass, who is also the top Democrat on the House Subcommittee on Africa. Rep. Bass introduced a bill calling for the U.S. government to “impose sanctions against Libya if the country fails to end slave auctions and other forms of forced labor”and hold accountable parties to human smuggling and trafficking as well as Libyan “detention center guards.” Rep. Bass’s resolution also calls for the U.S. Secretary of State and Administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Develop to use allocated funds to provide humanitarian assistance to migrants and refugees in Libyan detention centers. This bill urges the African Union to conduct its own independent investigation into the Libyan slave crisis. We commend African countries making efforts to facilitate the repatriation of captives; all those placing pressure on countries to adopt the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime; the shared commitments of the African Union, European Union, and United Nations (reached on Wednesday, November 29th) to work collectively to “freeze the assets of human traffickers” and refer them to the ICC; and, all those pressuring the international community to not only investigate but issue convictions. Lastly, as a research institution, we urge Africana scholars and practitioners to counter any evasion of the protracted history of abuses targeted at indigenous Black African ethnicities and cultural practices in North Africa so that present abuses may be placed in proper context and not rendered invisible or detached from a larger history of North African oppression targeting Black African people. Written by Serie McDougal III

Why do perpetrators of ethnic violence like to tinker around with definitions of their targets’ identities? This happens so much so that the international legal definition of genocide makes special note that perpetrators of such acts sometimes create identity labels for their benefit. In this tradition, the FBI has now created a label that it calls “Black Identity Extremist (BIE)” based on its evaluation of six cases between September 2014 and December 2016 where Black men (in particular) have targeted and killed police officers. An explanation can be found in a leaked FBI report on Black Identity Extremists. It states, “This intelligence assessment focuses on individuals with BIE ideological motivations who have committed targeted, premeditated attacks against law enforcement officers since 2014” (p.3). For Black people, it is hard to dismiss the FBIs long history of using sparse acts of resistance and violence against the state to create broad categories that have allowed them to label Black social movements, organizations, and individuals as ongoing threats to national security, such as Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Black Panther Party (Blackstock, Perkus, & Paul Avrich Collection, 1975). The report traces the trajectory of BIE activity to its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, exemplified by the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement, Black Liberation Army, and “Moorish Sovereign Citizen Ideology” and more recently its resurgence in response to the spate of police brutality in 2014. It states, “Convergence of BIE and Moorish Sovereign Citizen Ideology very likely leads to violence against law enforcement officers” (p.4). This framing allows law enforcement to take violent and extreme action against their targets, people they deem are troubling elements of American society. But the question that remains is, what does Black identity do to people of African descent at its higher levels? Scholars of Black racial identity generally define it as having a sense of pride in one’s collective and individual identity as a person on African descent and a sense of commitment to racial equity, justice, and freedom (Cross, 1971; Cunningham & Regan, 2012). Janet Helms and Thomas Parham (1996) conceptually define Black racial identity as a sense of collective identification based on one’s identity as a Black person. What are the attitudes and behaviors associated with Black racial identity in people of African descent based on the collection and analysis of empirical data? For example, the Racial Identity Attitude Scale (RIAS) uses a five-response agreement scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Racial identity at its upper levels has been found to be related to self-esteem and many other indicators of psychological well-being for Black people. The FBI, on the other hand, leaves the actual meaning of Black racial identity undefined. One thing that they do mention—which is highly contradicted by social scientific evidence—is the notion that Black racial identity at its higher levels is associated with violence. In sharp contrast to the unscientific claims made in this FBI report, Caldwell, Kohn-Wood, Schmeelk-Cone, Chavous & Zimmerman (2004) investigated the relationship between racial identity as protective factors against violence among African American adults. They found that the safe-guarding effects of racial identity were salient, particularly for men (a race/gender category highlighted by the FBI report). They also argue that the more central race was to their identities, the less violent behaviors Black men engaged in. It is in the interest of people of African descent to magnify and promote all social programs and practices that lead to positive Black racial identities at high levels. Anti-Black racial violence however, does lead to violence. A prime example of this is how the racialized use of excessive force and extrajudicial killings of Black people at the hands of law enforcement officials incites sometimes violent responses. Some Black males respond to racism by engaging in violence and other negative behaviors (Wilson, 1991). Given this empirical data, the notion that engaging in violence is the direct cause of Black racial identity is, in fact, false, and illustrates how Black identity and culture are demonized to sustain racist agendas. This prompts the question: does the FBI rendering of “Black identity extremism” then justify law enforcement’s use of excessive force? This seems to be what the FBI report suggests. What their own data corroborates is that the use of violence is caused by anti-Black racist violence toward Black people, the most common feature of the killings cited in the recent FBI report. Yet, they have chosen to identify Black racial identity as the cause in an effort to disrupt Black racial cohesion because they see it as undermining White power and privilege and the racial injustice that White America has and continues to benefit from. What again is it that sparks genocidal actors’ fascination with their victims’ identities? There is research conducted in which White American participants generally reacted more negatively toward strongly identified ethnic minorities, and those who identify strongly with their own ethnic identities (Sellers, Shelton & Diener, 2003). The authors of that research suggest that this occurs because Whites see them as rejecting the very status hierarchy that generally privileges Whites. Black people who identify with their Blackness is an existential threat to White supremacy. In the case of BIEs, the FBIs data set is not only unrepresentative, it is simply inaccurate but because of its clout as a government agency, it is positioned to contribute to dominant ideologies and fuel fear of Black communities’ embrace of healthy Black identity development that not only centers culturally relevant ways of being in the world, but also a clear view of the oppressive forces in it. Works Cited Blackstock, N., Perkus, C., & Paul Avrich Collection. (1975). Cointelpro: The FBI's secret war on political freedom (1st ed.). New York: Monad Press : Distributed by Pathfinder Press. Cross, W.E. (1971). The Negro-to-Black conversion experience: Towards a psychology of Black liberation. Black World, 20, 13–37. Cunningham, G., & Regan, M. (2012). Political activism, racial identity and the commercial endorsement of athletes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 47(6), 657–669. Caldwell, C. H., Kohn-Wood, L. P., Schmeelk-Cone, K. H., Chavous, T. M., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2004). Racial discrimination and racial identity as risk or protective factors for violent behaviors in African American young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 91-105. Helms, J.E., & Parham, T.A. (1996). The racial identity attitude scale. In R.L. Jones (Ed.), Handbook of tests and measurements for Black populations (pp. 167–174). Hampton, VA: Cobb & Henry. Sellers, R. , Shelton, J. , & Diener, E. (2003). The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 1079-1092. White, J. L., & Cones, J. H. (1999). Black man emerging: Facing the past and seizing a future in America. New York: W.H. Freeman. Wilson, A. N. (1991). Understanding Black male adolescent violence. New York: Afrikan World InfoSystems. Written by Serie McDougal

White slave owners associated several general characteristics with Black men, including weak, docile, and ignorant. There were also certain characteristics that enslavers did their best to deny to Black males, including authority, family responsibility, and property ownership (Dancy, 2012). However, White respect for these characteristics was not so cut and dry. Therefore, Black male exceptionalism represented the circumstances under which Whites recognized and respected characteristics of Black men that were contrary to these generalizations. For example, Marable (1994) explains that Black men during slavery were not praised or rewarded for being assertive, they were rewarded by Whites for being accommodating. Black men who were considered exceptional were those who were industrious and ethical and assertive. However, to earn the respect of Whites, their assertiveness must not be used to challenge the established order or White privilege. Black male assertiveness was acceptable as long as such Black men were pawns for Whites or that their assertiveness was used to support White power and privilege. For example, Black slave drivers were allowed to be assertive in forcing other enslaved Blacks to work and punishing their failure to do so. Athletic Blacks were allowed to use their physicality to entertain Whites. During slavery, Whites sometimes arranged events to force Black men to fight one another for entertainment. By all means, they were discouraged from fighting on behalf of other Blacks, particularly engaging in anti-slavery activism. Black male athletes engaging in political protest of police killings of Black males by kneeling during the U.S. National Anthem, are abandoning the model of Black male exceptionalism that has for so long reinforced White supremacy. President Donald Trump, in September 2017, made national headlines for redirecting focus away from police brutality, by framing football players as disrespectful to the U.S. flag and military (Hayward, 2017). After admonishing football team owners to fire football players, who he described as “sons of bitches,” when they refuse to stand for the national anthem. In keeping with his point that the players are being treated too softly, Trump draws on the stereotype of the Black male as a bloodthirsty brute and super athlete. He does this alongside expressing his disfavor for football rules designed to minimize head trauma that may lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). ESPN analyst Kevin Blackistone suggested that one reason Trump promoted a form of football that disregards traumatic brain injury is because most of the NFL players are Black males. Moreover, Black males are overrepresented among football positions that suffer the greatest levels of CTE (Moye, 2017; Weaver, 2017). Although President Trump’s rhetoric was shifting national dialog about protests away from the original political issue, the theme that remained consistent was lack of value for Black lives, in this case, Black male lives in particular. His comments harken back to antebellum beliefs that Black males could bear more pain and were less vulnerable to physical stress than their White counterparts. This racialized and gendered stereotyping has implications on Black males’ health status in general. James (1994) defines masculine self-reliance as a risk factor for John Henryism, a state of mental/physical vigor with a single-minded focus on hard work without regard to physical well-being. Some gender scholarship, according to Pass, Benoit & Dunlap (2014), exacerbates this problem in its repeated definition of Black masculinity as the hyper-version of every negative aspect of hegemonic White masculinity. Trump is using rhetoric that reinforces a great deal of gender scholarship about Black males as hypermasculine invulnerable beings. Black males’ break with racial gender stereotypes and exceptionalist expectations will always be seen as an ungrateful betrayal as President Trump has framed it. Works Cited Dancy, T.E. (2012). The brotherhood code: Manhood and masculinity among African American males in college. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc. Hayward, P. (2017, September 27). Trump unites his rivals by hijacking a courageous protest. The Daily Telegraph (London), p. 12. Marable, M. (1994). The Black male: Searching beyond stereotypes. In R.G. Majors and J.U. Gordon (Eds.), The American Black male. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers, pp. 69-77. Moye, D. (2017, September 25). Donald Trump prefers violent football so more Black players get hurt: ESPN analyst. Huffington Post, np. Weaver, C. (2017, September 27). MSNBC, huffpost: ‘Neanderthal’ Trump wants Black players to suffer. Newsbuster.org, np. Written by Serie McDougal

I grew up watching Michael Jordan on TV in an apartment on the South Side of Chicago. If you did that you would inevitably have to sit through commercials. I have to say that my favorite commercials were the ones that featured Jordan. Looking at the sacrifice and protest of Black male athletes today, I recall Jordan’s commercials. One that comes to mind is the “maybe I destroyed the game commercial” in which Michael Jordan explains his hard work, determination, sacrifice, and courage. I was always extremely inspired. I would be so caught up in the values he espoused. I remember being disappointed when I realized that the commercial gave the impression that Michael’s primary goal was individual greatness and basketball success, though you could apply those principles to anything. But why was that a problem? Why would Jordan appear so different to me than Muhammad Ali who public proclaimed he was the greatest of all time? Maybe the answers lie in the reasons why Jordan’s greatness was celebrated during his prime when Ali was so greatly ridiculed. Have Blacks been hindered in their pursuit of so called “traditional” manhood values such as independence, assertiveness, leadership & strength? Yes… and no. Players like Mahmoud Abdul Rauf, Craig Hodges, and Colin Kaepernick have exercised some of these values during their athletic tenures. However, their exercise of these values became a problem only when they began to support collective Black liberation and/or challenge anti-Black oppression. The purpose of this article is to locate the more recent forms of Black male athletes’ protest within the history of Black male workers’ political protest. For example, in the 19th century, northern Blacks were significantly impacted by European immigration. Employers preferred hiring Irish workers, therefore Blacks lost employment opportunities. Clarke-Hine and Jenkins (1999) explain that before 1820, Black craftsmen were in demand, although employers preferred to hire other Whites. By the 1830’s certain practices were used to successfully drive African Americans from skilled trades. Many Whites resented the idea of working alongside Blacks. These sentiments were made known through practices used by White workers to exclude Black men from apprenticeships. Sometimes White workers used terrorist attacks (i.e., lynching & bombings) to prevent employers from hiring Black men. In New York, for example, Black men were systematically prevented from achieving the advanced status of “cartman.” During that time, a major concern for Whites was Black collective advancement. In 1802, the postmaster general wrote to the U.S. senate that only Blacks should not be allowed to be mail carriers because the position would provide them a good opportunity to instigate and carry out revolts among the enslaved (Litwack, 1961). In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Black men were disproportionately represented among those who worked as seamen. Seafaring was less segregated than other labor forces in the 19th century. By no means was seafaring without racism, but maritime culture had a system of order, hierarchy, and mutual dependence that made the experience a more tolerable workplace for Black men compared to other industries (Bolster, 1990). This, in addition to the relatively high wages, and relatively less racial intolerance aboard vessels was attractive to Black men. Traditionally thought of as a manly occupation, being a seaman also offered Black males opportunities that would typically not be available to them. Enslavers sometimes hired enslaved Black men out to work aboard ships to receive their wages (Bolster, 1990). Some Black men, eager to make an escape or to temporarily get relief from the high level of racist hostility ashore, sought out seafaring. Indeed, the prominent Black advocate for freedom and liberation, Frederick Douglass, sought his escape aboard a ship. On the heels of Denmark Vesey’s plan for revolt, South Carolina passed legislation (Negro Seamen Acts) deterring Black men from seafaring. Some of the laws required that Black seamen be imprisoned upon arrival in South Carolina until their vessels departed, with their captains paying the expenses of their detention (Bolster, 1990). South Carolina passed Act for the Better Regulation and Government of Free Negroes and Persons of Color, because they feared that Black seamen would infect other Blacks with the spirit of revolt. They were correct, Black seamen, as early as 1809 participated in the distribution of abolitionist materials (Bolster, 1990). They were the defiant ones. Muhammad Ali became legendary and iconic because he refused to submit to the pressure. Harshly ridiculed during his time and admired in death, Ali took the road less travelled by; he was the greatest, but he stood for something greater. Something greater than personal success costed many of our ancestors’ wealth and prestige, but gained them eternal glory. As many football players have pledged to continue to kneel during the national anthem whether Colin Kaepernick does or not, pressure on them will continue to mount. The questions that remain are, will current athletes sustain this movement and will Black people translate the spirit of Black athletes protest into social and political advancement in the settings where we live and work? Works Cited Bolster, W. J. (1990). "To feel like a man": Black seamen in the northern states, 1800-1860. Place of publication not identified: publisher not identified. Clarke-Hine, D. & Jenkins, E.(Ed.) (1999). A question of manhood: A reader in U.S. Black men’s history and masculinity. Bloomington, IA: Indiana University Press. Litwack, L. F. (1961). North of slavery: The Negro in the free States, 1790-1860. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Reese, F. (2017, August 31). Sidelined, silenced: Unsigned Kaepernick highlights limits of free speech in sports, workplace. Atlanta Black Star. Retrieved September 01, 2017, from http://atlantablackstar.com/2017/08/31/sidelined-silenced-unsigned-kaepernick-highlights-limits-free-speech-sports-workplace/ Written by Sureshi Jayawardene The Urban Institute, a think tank specializing in economic and social policy, recently issued a report, “Why Does Cash Welfare Depend on Where You Live?” exploring the variation in state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) policies and the factors that might explain these differences. TANF is the primary government program associated with cash welfare and provides cash assistance to low-income families with children. Black families are hyper aware of this weak social safety net and understand the racialized nature of this system in its failure to help those who need it most. Black communities also already know that race is key to the implementation of TANF. However, the Urban Institute’s study shows the importance of a deeper awareness of why benefits vary by state. The central goal of TANF, since 1996, has been to help curb poverty. Welfare reform implementations of 1996 significantly changed the structure of TANF. When Clinton created TANF twenty years ago to replace, AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children), states were afforded much greater flexibility in the disbursement of benefits. Each state uses its federal TANF block grant to fund its own unique TANF program. Whereas with AFDC, the federal government shared the burden of any heightened need and costs with states which meant that funding rose automatically, with the block grant design of TANF states receive a fixed amount of money regardless of the volume of people who qualified for benefits. According to the Urban Institute, differences in TANF benefits by state result from states’ broad authority to establish rules related to:

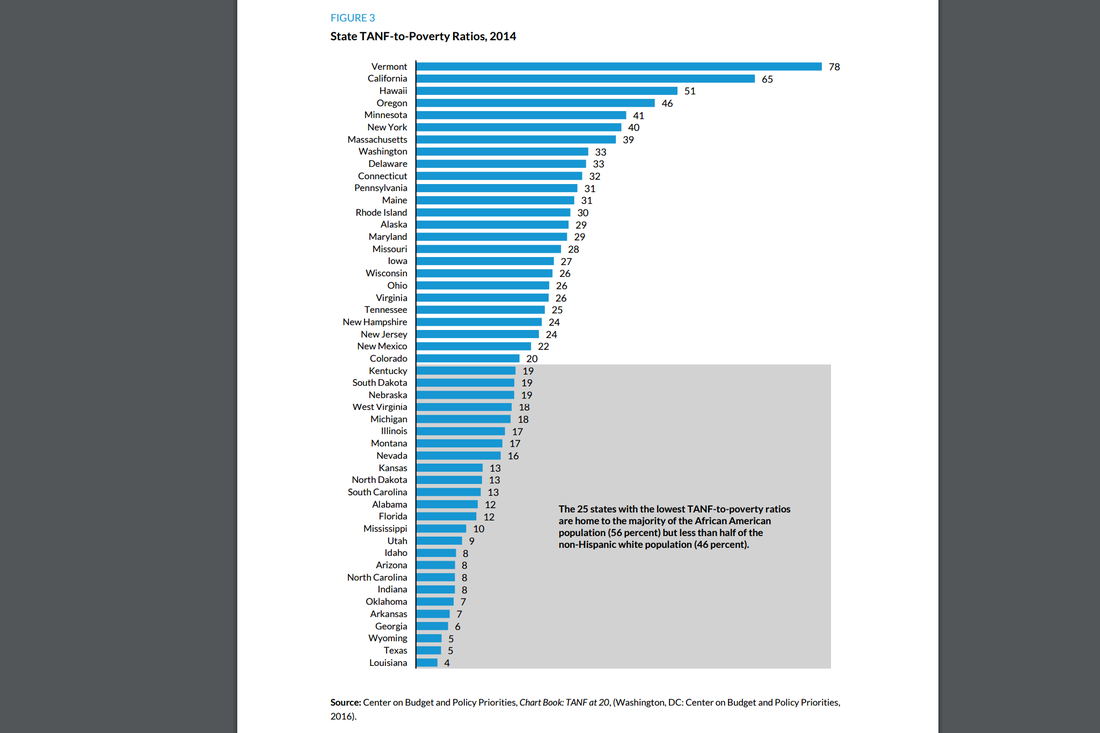

Congress has done little to adjust these fixed funds for inflation and other factors, which means that funding levels have eroded and not seen an increase since then. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, due to the fundamental design of TANF, states reach far fewer poor families than they did with AFDC. Therefore, the number of families benefiting from the program has been on the decline, without any significant shifts to poverty rates in the nation. For example, in 2013-14, for every 100 families living in poverty, only 24 families received TANF. This figure fell to 23 in 2015. In 2016, in an average month, 1.5 million families—that is, only 1% of the total population—received TANF cash benefits, and nearly 40% of these families received benefits only for children in the household. The TANF-to-Poverty Ratio The Urban Institute reports that although the TANF-to-Poverty ration has fallen in every state except Oregon, the difference among states has increased. For instance, in 1998, for every 100 families with children in poverty, the state of California provided cash assistance to more than 3 times as many families as Texas did. By 2013, this ratio had grown to 13 times as many families. Between 2013 and 2014, Louisiana, Texas, and Wyoming provided TANF to fewer than 5 families for every 100 with children in poverty. The report highlights that the majority of African Americans lives in states that provide TANF cash assistance to no more than 19 families for every 100 families living in poverty. The majority of non-Hispanic White people live in states that provide TANF to at least 20 families for every 100 living in poverty. Here is one of the ways the policy has racially disproportionate effects. The Urban Institute analyzed TANF policies of each state, organizing them into three broad categories: generosity, restrictiveness, and duration. Their findings were key to the racialized and racist nature of the delivery of TANF benefits. For instance, researchers found that the racial demographics of a state were central to how generous or restrictive a state’s TANF policies were. According to them, African Americans as well as other groups of color are highly concentrated in states where TANF policies are less generous with maximum benefits, more restrictive on behavior, and stipulate shorter time limits on families. African American families, in particular, are concentrated in states with harsher, more restrictive TANF policies.

Trump’s Budget and TANF The Trump administration recently released its budget outline which involves major changes to social safety nets, including dramatic cuts to the country’s only cash assistance program, TANF. Critics of the Trump budget blueprint have called attention to the severe underfunding of TANF in the past two decades, which means the program would be further stifled and ineffective in achieving its objectives under the current administration’s proposed budget. Trump aims to cut TANF funds by $21 billion over the course of a decade and reduce the amount of federal funds to states to deliver benefits by $15.6 billion. This budget also proposes the elimination of TANF contingency funds, which account for funding needs when an economic crisis increases pressure on the program. According to the White House, this budget “strives to replace dependency with the dignity of work through welfare reform efforts.” The Urban Institute’s findings and the budget proposal of the Trump administration demonstrate that access to welfare for poor families would be further restricted. Poor Black families are likely to find themselves even more ineligible with Trump’s proposed welfare cuts. Written by Serie McDougal

It was a steamy hot July in1955. A young Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to the podium at the Holt Street Baptist Church in the midst of a Bus Boycott to end the segregation aboard buses in Montgomery, Alabama. He began giving a riveting speech to the crowd who was gathering confidence and inspiration that they could eventually break the back of Montgomery County and force it to end segregated seating aboard buses. However, King noticed that people began to enjoy the carpooling system they had created as an alternative. He had been hearing rumblings among the congregation that people were proud of the system they started because it was a creation all their own. Moreover, they enjoyed one another’s company. They began to get to know one another on a different level. They enjoyed being together in the interest of advancing the Black community. They became more interested in expanding this new experience instead of integrating Montgomery’s busing system. As King read the crowd, he abandoned his prewritten speech as proclaimed, “I want you to realize the gravity of what you have created. You have claimed something that Montgomery was never capable of giving you. Something more valuable than sitting next to someone who is White? You have claimed your freedom, and you have experienced what that feels like. Let’s not end that! Let’s not end this bus boycott! Let us build and sustain it in perpetuity! Let's call it ‘The Harambee Transportation Company’.” The rest is history. Obviously, the above is an alternative history of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. But why reimagine such a momentous accomplishment? More specifically, how is it relevant to the work experiences of Black people today? People tend to perform better on their jobs when they are respected at work and find their jobs interesting and fulfilling. Many African Americans do not have this experience in large part due to racism. In Chicago, seven African American, current and former employees of the water department are a part of a class-action lawsuit charging that they were and are subjected to systematic denial of promotions and routine racial and sexual harassment. Yet, racism is said to be bad for business because it denies companies the best and the brightest due to their race. Well, then why engage in systematic bias over a protracted period of time and foster a culture of White supremacy if the market accepts the logic that racism is bad for business? Milton Friedman argued that capitalism was fundamentally good and racism doesn’t make sense because the pressure to make money will force employers to not make decisions based on race. Racist math doesn’t work according to this logic. Answering this question requires a different calculus. The country may lose billions of dollars annually due to employment discrimination that causes loss of productivity and talent. However, according to the crowding hypothesis as articulated by Bates & Fusfeld (2005), when Black people are crowded into lower paying jobs and systematically denied promotions, their wages will go down or do not rise. Non-Black workers benefit from this because it takes them out of competition with Black workers, making it easier for their wages to rise (Bates & Fusfeld, 2005). The other kind of capital not accounted for in the logic that racism is bad for business is the psychological capital that is gained from the sense of superiority that is fed by routinized racial harassment. The same logic applies to sexual harassment but combined with racism the experience is far more pervasive transcending labor markets and class divisions. However, did the Montgomery Bus Boycott prove Friedman’s logic correct? Did it prove that racism, in fact, is bad for business? In fact, it resulted in a collective action model that gave the civil rights movement a blueprint. However, racism has found new and more resilient means of resisting this economic logic, as it has in Chicago’s water department. But, imagine for a minute, what would have happened if the Montgomery Bus Boycott had never ended. Perhaps, the outcome would have been a Black owned transportation company. Maybe it would have been a model for Black owned business expansion in similar cities across the country. The Black liberation struggle has developed many methods for advancement. For example, the NAACP has made clear the role that legal action plays in challenging racism. An additional solution to job discrimination may come from moving the creation of Black businesses up the priority list from an “alternative” to a “primary” method of creating work opportunities for Black people in which they are respected, fulfilled, and stimulated. Bates, T. & Fusfeld, D. (2005). The crowding hypothesis. In C.A. Conrad, J. Whitehead, P.L. Mason & J. Stewart (ed), African Americans in the US economy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 101-109. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed