|

Written by Serie McDougal

Georgetown University’s Center of Education and the Workforce recently produced a report on African American college students’ choices for majors and how those choices affect their earnings. Based on the findings, African Americans students’ choices of majors tend to be concentrated in service oriented academic disciplines. The top ten college majors by percentage of African American degree holders are: 1) Health and Medical Administration Services, 2) Human Services and Community Organization, 3) Social Work, 4) Public Administration, 5) Criminal Justice and Fire Protection, 6) Sociology, 7) Computer and Information Systems, 8) Human Resources and Personnel Management, 9) Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, and 10) Pre-Law and Legal Studies (Carnevale, Fasules, Porter & Landis-Santos, 2016). African American students’ interest in service oriented occupations also means that they are concentrated among the lowest earning jobs because of the lack of value that the U.S. places on service-oriented work. African American students are underrepresented among fast growing and high earning disciplines such as business and engineering majors and other STEM fields (Carnevale, Fasules, Porter & Landis-Santos, 2016). Sometimes called the “caring professions,” human services and community organization, health and medical administration services, and social work, are among the fields that African Americans are most highly represented, yet they rank among the lowest incomes. As informative as the report is, its conclusion seems to be lacking in context as it suggests that African American students must simply make better choices, major in growing, high earning STEM fields. The implication being that if they majored in fields related to higher earnings, they would experience more financial success and less stress. What about how African American underrepresentation in STEM fields develops. African American youth in K-12 school, often attend under-resourced schools that: 1) are less likely to offer high-level math and science classes, 2) are less likely to offer rigorous high quality math and science courses when they are offered, and 3) more likely to have math and science teachers teaching outside of their fields (Anderson, 2006). The idea that they enter college with a disadvantage regarding their relative levels of preparation for such majors is not lost upon them. Expecting Black students to simply choose STEM fields without addressing these structural inequalities in their pre-secondary schooling experiences is disingenuous at best. Debunking internalized racism in the form of beliefs that Black people are less capable in scientific fields has its place, as does exposing Black youth to curriculum that fills them with knowledge of their people’s rich scientific heritage. Exposing them to professional mentors in STEM professions as early as middle and high school would offer them concrete examples of the possible in addition to invaluable mentorship. But, one thing is for certain, simply admonishing Black students to make better choices is the symbolic racist counterpart of the institutionally racist structures that disadvantage them before they reach college. Works Cited Anderson, E. (2006). Increasing the success of minority students in science and technology.Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education. Carnevale, A. P., Fasules, M. L., Porter, A., & Landis-Santos, J. (2016). African Americans: College majors and earnings. Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved December 27, 2016, from https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/AfricanAmericanMajors_2016_web.pdf National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) (2016). Indicator 24: STEM Degrees. Retrieved December 26, 2016, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_reg.asp

0 Comments

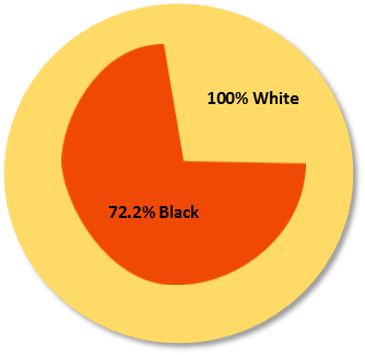

Written by Serie McDougal and Sureshi Jayawardene Malcolm X once stated in an interview- "If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, that's not progress. If you pull it all the way out, that's not progress. The progress comes from healing the wound that the blow made. They haven't even begun to pull the knife out. They won't even admit the knife is there." The National Urban League (NUL) releases a report on the State of Black America (SOBA) every year. The NUL have, arguably, the best metric for measuring the collective conditions, needs, progress, and regress for Black America. This metric is called the Equality Index. It was designed to assess the relative status of Black and White people and, more recently, Latino/Latina Americans. The Equality Index assesses the progress toward achieving equal social, political, and economic opportunity between Blacks and Whites in the United States. Year-long analyses result in a score representing relative progress made toward equality. The Equality Index score is a calculation based on five areas of Black life: economics, health, education, social justice, and civic engagement. The score is in the form of a percentage between 0 and 100%, with 100% representing complete equality with Whites. The 2016 Equality Index for Black America for 2016 is 72.2% (Figure 1). To summarize, the most recent equality index scores show that there have been improvements in the areas of education (76.1% to 77.4%), economics (55.5% to 56.2%) and social justice (60.6% to 60.8%). The most significant percentage point increase is in educational parity. SOBA analysis shows that the improvements in education are a results of the fact that Black college attainment and enrollment rates have increased in the past year. This means that more African Americans are attending college and attaining higher levels of education (i.e. more African Americans attaining a college degree or higher). The improvements in economics are a result of progress in closing the digital divide and more Black people getting approved for mortgage and home improvement loans. The improvements in social justice are a result of lower incarceration rates for African Americans and higher rates of imprisonment for Whites following arrests.

Although these changes are statistically marginal, they are important. Educational attainment is important because it is related to employment and income which both increase people’s access to health and housing (Belgrave, 2010). Improvements in the percentage of Blacks with at least a bachelor’s degree and greater college enrollment explains the educational parity for SOBA this year. 2016 marks the 40th anniversary of SOBA and researchers analyzed data between 1976 and 2016 to determine exactly what changes have taken place in this time frame. Unlike in 1976, today, approximately a third of 18 to 24-year-old Blacks are enrolled in college. In addition, the percentage of African Americans with a bachelor’s degree or higher has more than tripled since 1976 (6.6%). However, college graduation rates and access to high quality elementary and secondary education remain major concerns. Another area of Black life that deeply influences the equality is in terms of incarceration. Moreover, discrimination in arrests is a violation of the 14th amendment’s guarantee of equal protection (Walker, Spohn & DeLone, 2004). Unequal enforcement of the law is at the heart of the matter, and the enhanced advocacy amount police conduct may have influenced recent shifts in arrest rates for Whites. Two areas experienced decline in the past year: civil engagement (from 104.0% in 2015 to 100.6% in 2016) and health (from 79.6% in 2015 to 79.4% in 2016). The sharp decline in civil engagement is reflective of typical drops in voter registration and participation during midterm election years. Revisiting the Notion of Progress In the beginning of each report, there is typically an important note contextualizing the meaning of progress. The recently released 2016 report is no different. The NUL explains that although there have been changes in the collective conditions of African Americans, stark inequities remain a problem. Moreover, there must be policies that that are targeted enough to improve the collective conditions of African Americans. NUL’s report indicates that progress must be defined and articulated on our own terms, rooted in our own objectives for our collective welfare and futures. “The Main Street Marshall Plan: Moving from Poverty to Prosperity “ The 2016 SOBA Report offers a comprehensive and sophisticated plan of action to address the areas of concern highlighted in this year’s Equality Index. NUL is calling for a $1 trillion investment in Black America to substantially improve equality in education, civic engagement, social justice, jobs and economic opportunities, and healthcare. This has been pitched as a multi-annual, multi-pronged commitment over the next five years. This plan would address: universal early childhood education, a federal living wage of $15/hour, comprehensive urban infrastructure, small and micro business financing plan target for women and minority owned business, expanded summer youth programs, expanded home ownership strategies, expanded Earned Income Tax Credit, expanded re-entry workforce training programs, doubling Pell Grant program, expanded financial literacy and home-buyer counseling, expanded Section 8 program, Green Empowerment Zones in high unemployment areas, increased federal funding to local schools, and affordable high-speed broadband. The Main Street Marshall Plan focuses on rebuilding and innovating infrastructure in urban communities where high concentrations of Black youth and families continue to suffer due to malfeasance and indifference. It may be useful for reparations advocates such as NBUF, NCOBRA, and others to consider The Main Street Marshall Plan as a vehicle for how African American communities might use reparations funds to better our life chances. Works Cited Belgrave, F. & Allison, K. (2010). African American psychology: From Africa to America. Los Angeles: Sage. Walker, S., Spohn, C. , & DeLone, M. (2004). The color of justice: Race, ethnicity, and crime in America. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. |

Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed