|

Frankly, the Black community must be concerned with obesity because of its painful and often deadly relationship to chronic diseases like arthritis, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases and its subsequent impact on families and communities. Compared to White Americans, Black people with these conditions are more likely to die because they are less likely to have access to higher quality health care. For the U.S. Government, it is obesity’s $1billion cost to Medicare and Medicaid that has earned it the label, ‘public health crisis’ (Harding, & Lovenheim, 2017). Given politicians’ and the Black community’s differing framings of the problem of obesity: public policy solutions and the wellbeing of the Black community are often misaligned. Let’s contextualize this problem. The prevailing logic of price based intervention passes the test for face validity: raising prices for unhealthy foods should influence people to consume less of those foods, resulting in better overall health (Webber, 2017). However, the impact of these policies has much more complex effects. For instance, Finland raised taxes on sweets by 14% yet, consumptions only decreased marginally. Denmark also increased its taxes with only marginal outcomes (Webber, 2017).

It’s not the snickers, it’s the sugar…okay maybe both! One thing that policies of the past did not consider is consumer substitution. Consumers often switch to cheaper substitutes when products that are taxed heavily. If a Hawaiian Punch is a bit too much, then a Tahitian Treat or a Shasta may work instead. This is why poor dietary habits and health outcomes remain resilient. Some consumers challenge the laws and even the geography of taxes on their calories. The Danish government found that it was losing money as people began to increase their illegal sale of soft drinks, while others crossed into neighboring countries (Germany and Sweden) to purchase their soda without the high taxes (Webber, 2017). To avoid the substitution problem, Harding & Lovenheim (2017) suggest that misguided product based taxes be replaced by nutrient specific taxes. They hypothesize that a product based tax (i.e. on soda) would be far less effective than a nutrient tax (i.e. a tax on sugar). They propose the creation of nutritional clusters of product types (diet and regular soda, sliced bread and pastries, candy and cookies). Based on their predictive research using Nielson Homescan consumer data, they found that while a product-specific tax on soda may decrease total purchased calories by 4.84% and sugar consumption by 10%, a 20% sugar tax decreases total calories by 18% and sugar by 16%. This would limit the substitution effect. Within-Group Differences Price shifts may also have differential impacts within racial populations. Pitt & Bendavid (2017) developed a model to predict the 15-year impact of increases in meat prices. They found that only extreme price increases (greater than 25%) would actually result in reductions in obesity (Pitt & Bendavid, 2017). Additionally, they found that increasing meat prices resulted in higher life expectancies, although the impact was not felt evenly across race. White male and Black females benefited the most. The authors theorize that this is in part because the benefit was greatest among those who were overrepresented among the initially overweight, and the fact that they were more likely to avoid mortality at elevated body mass indexes. Black males benefited the least because more of them shifted into the category of low Body Mass Index (BMI), while their risk for mortality as a group is greater at low BMIs compared to other groups. This research suggests that more targeted interventions be undertaken instead of relying on broad-based product and/or nutrient taxes. This is only part one of a set of articles on this topic, stay tuned. Works Cited Harding, M. , & Lovenheim, M. (2017). The effect of prices on nutrition: Comparing the impact of product- and nutrient-specific taxes. Journal of Health Economics, 53, 53-71. Pitt, A. , & Bendavid, E. (2017). Effect of meat price on race and gender disparities in obesity, mortality and quality of life in the us: A model-based analysis. PLoS One, 12(1). Webber, P. (2017). Nobody loses fat on sugar taxes-especially governments. The Times and Transcript, March, 7th, p. A.9.

0 Comments

The Impact of Racially Biased Perceptions about Black Men’s Physical Size and Formidability3/16/2017 Written by Sureshi M. Jayawardene

A new study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology this month reveals a correlation between the physical size of Black men and the disproportionate police targeting of unarmed Black men. Wilson, Hugenberg, and Rule’s (2017) study showed that people generally have a racially biased perception that Black males are bigger (i.e., taller, heavier, and more muscular) and more physically threatening (i.e., stronger and more capable of causing harm) compared to similarly sized young White men. Such perceptions are central to conversations about police violence in the Black community. We know that racism and White supremacy are the culprits for the violence of policing, but how can we better explain the systematic and sustained patterns of police officers’ force decisions? What real, hard evidence can we bring forward to overhaul the current system of policing so that our loved ones are not moving targets? One dimension of police altercations in the Black community that always functions to incriminate the dead—and often unarmed—Black youth and justify the police officer’s decision to use force (not just one time but multiple times) is the victim’s physical size and formidability. Wilson et al (2017) hypothesized that the stereotypes that Black men are “physically threatening,” “less innocent,” and “physically superhuman” likely creates conditions that prompt perceivers to demonstrate racially biased perceptions of Black men’s physical size and overall formidability. Biased Formidability Judgment In this study, Wilson et al (2017) conducted a series of experiments with over 950 online participants across the United States who were shown a number of color photographs of White and Black male faces who were of equal height and weight. Study participants were then asked to estimate the weight, strength, height, and overall muscularity of the individuals in the images. The researchers found that the estimations were “consistently biased” evidenced by claims that judged Black men to be larger, stronger, and more muscular than their White counterparts, although they were the same size and build. Study participants also expressed that Black men had a greater capacity to cause harm in a hypothetical altercation. Furthermore, and rather distressingly, participants also believed that law enforcement would be more justified in using force to subdue Black men even in situations where they were unarmed. In one experiment, participants were shown identically sized bodies which were either labelled Black or White. Participants were more likely to describe the Black bodies as heavier and taller. In another experiment, this size bias was especially evident for men whose facial features were more stereotypically “Black,” i.e., Black men with darker skin and facial characteristics that were more “African.” These images elicited more biased size perceptions despite these men being the same size as their lighter skinned counterparts with less stereotypical facial features. Noteworthy in these findings is that even study participants who identified as Black displayed this racial bias. However, key to this finding is that while Black participants judged young Black men to be more muscular than their White counterparts, they did not assess them to be more inclined to cause harm or to be more deserving of force. Research for Social Change Black communities nationwide are intimately familiar with the disproportionate and gratuitous police violence Black men, women and transpersons are routinely subjected to. Across geographies and generations, Black people know this all too well. Many experience repeated trauma with word of each police killing. Often, this reality of Black death is so close to home that we do not need research to support it. However, this new study demonstrates one dimension of the possible cause between disproportionate police targeting and racial bias within law enforcement as a system. In other words, Wilson et al (2017) provide us evidence that may explain one contributing factor of police officers’ decisions to shoot an unarmed Black man. Limitations and What’s Needed Next Although this study illustrates the relationship between misperceptions of Black men’s size, threat, and the use of force, the researchers did not simulate real-world threat scenarios such as those Black youth and police officers find themselves in. Wilson et al (2017) note that further research into whether and how this bias operates in potentially lethal situation as well as other real-world police interactions is necessary. Moreover, the study participants were also not exclusively representatives of law enforcement agencies, which means that more research needs to be done to empirically establish the relationship between racially biased perceptions about Black males’ size, their proclivities for causing harm, and the use of force in this specific context so that real, effective, and sustainable solutions can be formulated. Works Cited Wilson, J.P., Hugenberg, K., and Rule, N. (2017). Racial bias in judgments of physical size and formidability: From size to threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000092 Written by Serie McDougal

In a country that has done little to gain the faith of Black males, what role does trust play in the formation of Black manhood in the American context? T. Elon Dancy (2012) interviewed 24 African American males at 12 different universities about the intersections of manhood and the college experience. One of the things that Dancy (2012) identified is the different ways that his respondents defined manhood in the context of their college experience. Dancy (2012) discovered three elements of manhood based on his interviews: 1) self-expectation; 2) relationships and responsibilities, and 3) worldviews and life philosophies. Self-expectation represents the emphasis that the young men placed on manhood as being self-determining, responsible, being a real or authentic version of one’s self, being leaders, and being able to balance sensitivity and strength. Relationships and responsibilities represent the young men’s association of manhood with being provider and protectors of women and children and being examples for their younger siblings and relatives. Worldviews and philosophies refer to the men’s association of manhood with being spiritual, having a certain level of skepticism or mistrust of Whites, embracing African American and African culture, and serving and supporting the Black community. The third theme, worldviews and philosophies, is evidence that some college-age Black males defined manhood in a way that includes having a distrust for Whites. This phenomenon is called “cultural mistrust” in the mental health arena. Given the degree to which African Americans are stereotyped and subjected to institutional racism, Ridley (1989) regards this a healthy mistrust. This interpretation of mistrust as healthy allows Blacks to protect themselves from racist experiences that may be harmful to their self-esteem. More recent research suggests that trust may be related to the educational phenomenon called disidentification. Academic Disidentification A great deal of academic research on African American youth examines a phenomenon called academic disidentification. Simply put, academic disidentification occurs when a student’s self-perception is not impacted by their academic performance as it does for most others. For individuals who are academically disidentified, poor academic performance will not impact their self-esteem. Black students have been found to be more likely to academically disidentify compared to other groups. Although academic disidentification develops over time, yet for Black males who disidentify do so more consistently over time compared to Black females. In a new study, McClain & Cokley (2016) explore the reasons why this happens. Teacher Trust The evaluation of teachers is a major component of students’ academic achievement. A component of the teacher-student relationship is teacher trust or students’ trust of their teachers and beliefs that they are benevolent, honest, reliable, open, and competent. McClain and Cokley (2006) recently investigated the roles that teacher trust and gender play in disidentification among 319 college students, who self-identified as Black. They used a trust scale to measure students’ differing levels of trust in their teachers, and an academic self-concept scale to measure higher and lower levels of academic self-concept. The results illustrate that Black males reported significantly lower levels of trust and GPAs compared to Black females. Older males reported higher levels of academic self-concept, while this was not true for females. While older males had lower levels of trust, older females had higher levels of trust. Among Black male and female students, those with high academic self-concept were likely to have higher levels of teacher trust. Moreover, males and females with higher GPAs were likely to have higher levels of trust. This means that while males developed higher academic self-concepts over time, they also developed lower levels of trust in their teachers. McClain & Cokley (2016) explain that older Black males may be discounting feedback from their teachers. They suggest a lack of teacher trust may explain why there is a weak relationship between Black males’ academic self-concepts and their academic performance. It is also possible that this is because when they distrust their teachers, they attribute their academic outcomes to their teacher’s bias. Besides, their teacher perceptions are out of their hands, which may give them the feeling that their academic fate is also out of their hands (McClain & Cokley, 2016). Addressing Disidentification and Teacher Trust To ameliorate the problem of academic disidentification and address issues of teacher trust among Black college students, the authors of this study suggest that teachers need to interrogate their own perceptions of Black males, challenge their racial attitudes, and seek ways to build trust with Black males. However, another important solution lies in an earnest effort at recruiting Black faculty, especially Black male faculty. Compared to their non-Black professors, Black students have found Black professors to be less likely to treat them stereotypically, more likely to have positive beliefs about their academic ability, understand them, be role models for them, and hold them to high standards (Guiffrida, 2005; Tuitt, 2012). Dancy, T.E. (2012). The brotherhood code: Manhood and masculinity among African American males in college. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc. Guiffrida, D. (2005). Othermothering as a framework for understanding African American students' definitions of a student-centered faculty. Journal of Higher Education, 76(6), 701-723. Mcclain, S., & Cokley, K. (2016). Academic disidentification in black college students: The role of teacher trust and gender. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. Ridley, C. R. (1989). Racism in counseling as an adversive behavioral process. In P. B. Pedersen, J. G. Draguns, W. J. Lonner, & J.E. Trimble (Eds.), Counseling across cultures (3rd ed., pp. 55–77). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Tuitt, F. (2012). Black like me. Journal of Black Studies, 43(2), 186-206. Written by Serie McDougal

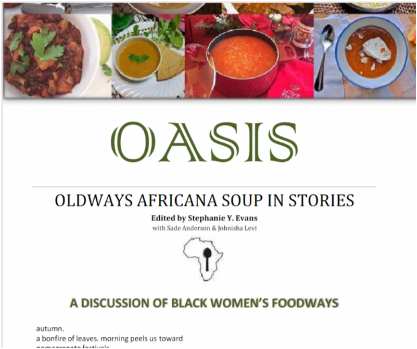

Georgetown University’s Center of Education and the Workforce recently produced a report on African American college students’ choices for majors and how those choices affect their earnings. Based on the findings, African Americans students’ choices of majors tend to be concentrated in service oriented academic disciplines. The top ten college majors by percentage of African American degree holders are: 1) Health and Medical Administration Services, 2) Human Services and Community Organization, 3) Social Work, 4) Public Administration, 5) Criminal Justice and Fire Protection, 6) Sociology, 7) Computer and Information Systems, 8) Human Resources and Personnel Management, 9) Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, and 10) Pre-Law and Legal Studies (Carnevale, Fasules, Porter & Landis-Santos, 2016). African American students’ interest in service oriented occupations also means that they are concentrated among the lowest earning jobs because of the lack of value that the U.S. places on service-oriented work. African American students are underrepresented among fast growing and high earning disciplines such as business and engineering majors and other STEM fields (Carnevale, Fasules, Porter & Landis-Santos, 2016). Sometimes called the “caring professions,” human services and community organization, health and medical administration services, and social work, are among the fields that African Americans are most highly represented, yet they rank among the lowest incomes. As informative as the report is, its conclusion seems to be lacking in context as it suggests that African American students must simply make better choices, major in growing, high earning STEM fields. The implication being that if they majored in fields related to higher earnings, they would experience more financial success and less stress. What about how African American underrepresentation in STEM fields develops. African American youth in K-12 school, often attend under-resourced schools that: 1) are less likely to offer high-level math and science classes, 2) are less likely to offer rigorous high quality math and science courses when they are offered, and 3) more likely to have math and science teachers teaching outside of their fields (Anderson, 2006). The idea that they enter college with a disadvantage regarding their relative levels of preparation for such majors is not lost upon them. Expecting Black students to simply choose STEM fields without addressing these structural inequalities in their pre-secondary schooling experiences is disingenuous at best. Debunking internalized racism in the form of beliefs that Black people are less capable in scientific fields has its place, as does exposing Black youth to curriculum that fills them with knowledge of their people’s rich scientific heritage. Exposing them to professional mentors in STEM professions as early as middle and high school would offer them concrete examples of the possible in addition to invaluable mentorship. But, one thing is for certain, simply admonishing Black students to make better choices is the symbolic racist counterpart of the institutionally racist structures that disadvantage them before they reach college. Works Cited Anderson, E. (2006). Increasing the success of minority students in science and technology.Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education. Carnevale, A. P., Fasules, M. L., Porter, A., & Landis-Santos, J. (2016). African Americans: College majors and earnings. Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved December 27, 2016, from https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/AfricanAmericanMajors_2016_web.pdf National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) (2016). Indicator 24: STEM Degrees. Retrieved December 26, 2016, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_reg.asp Written by Sureshi M. Jayawardene “OASIS: Oldways Africana Soup in Stories” is a collection of Black women’s recipes and life stories, curated by Dr. Stephanie Y. Evans. In collaboration with Sade Anderson and Johnisha Levi, Dr. Evans has compiled an electronically accessible collection of “culturally-informed soup recipes” that help expand our knowledge of Black women’s nutritional practices, knowledge, and wellness. OASIS offers personal vignettes and recipes that “explore identity, geography, health, and self-care.” This recipe book brings together the “20 cooks, chefs, researchers, storytellers, foodies, farmers, nutritionists, historians, activists, food bloggers, and wellness workers” to increase our understanding of Black women’s health and wellness practices. Furthermore, Dr. Evans has taken a sweeping diasporic approach, featuring soup recipes and narratives from Nigeria to Guyana, to Tobago, the Carolinas, and New Mexico. She writes that “soup is a perfect meal that allows us to simmer down” and invites readers to draw inspiration from OASIS to document their own stories and recipes, but also to expand their own wellness menus. Dr. Evans stresses that Black women’s wellness is an afrofuturistic situation and draws on Anna Julia Cooper’s notion of “regeneration”: that we look to the past for wisdom, the interior for strength, and the future for faith and hope. Dr. Evans herself offers a recipe that forms part of her self-care regimen: Green Chile Chicken Stew! She describes why it is such a staple for her, given her own busy routine and lifestyle. Green Chile Chicken Stew Dr. Evans’ recipe for Green Chile Chicken Stew is one of many easy-to-make, nutritious, and culturally grounded modes of exploring and uncovering Black women’s nutritional knowledge and practices.

OASIS can be accessed HERE. Look, download, read the life stories, try out the soups, and help support the important work that Dr. Evans has embarked upon. In a time when nutrition, fitness, and healthy lifestyles are trendy and gaining momentum through social media platforms, OASIS and Dr. Evans’ work is critical for how Black communities approach health and wellness in culturally rooted ways. Combining age-old family recipes that Black women have passed down and newer on-the-go recipes that Black women have created as they have moved through various circumstances provide a unique platform for more Black women to participate in. Whereas physical books face the threat of obsoleting with the high saturation of digital modes of health and wellness, OASIS gives us something tangible with its compilation of Black women’s history, nutritional wisdom and practices, and Black women’s life stories. One of the potential outcomes of OASIS and the individuals involved in this work is that it doesn’t just promote health and wellness among Black women, but encourages us to look deeply at our historical and cultural stores for how to address our nutritional needs, food consumption, and overall wellness and health. Written by Serie McDougal

A common pattern among pre-colonial African initiation rites of adolescent males involved removing boys from the immediate community to guide them through a series of collective tasks, while under the leadership of older males and elder males. The objectives at this age were above all, educational, often to teach boys discipline, to be courageous, how to deal with fear, to bond with other males, and for older males to take responsibility for their younger peers, and to teach boys to listen to and obey their elders (Mazama, 2009). These communally formed male bonds set the stage for healthy brotherhood between men. Black Brotherhood in the Antebellum Period There is not a great deal of literature on brotherhood between Black men during slavery. However, in the recently published text, My Brother Slaves: Friendship, Masculinity, and Resistance in the Antebellum South, Sergio Lussana discusses many aspects of Black manhood during slavery. One of the areas that he focusses on is Black male friendship. Lussana begins with a quote from the formerly enslaved abolitionist, Frederick Douglass: “For much of the happiness, or absence of misery, with which I passed this year, I am indebted to the genial temper and ardent friendship of my brother slaves. They were every one of them manly, generous, and brave; yes, I say they were brave, and I will add fine looking. It is seldom the lot of any to have truer and better friends that were the slaves in this farm. It was not uncommon to charge slaves with great treachery toward each other, but I must say I never loved, esteemed, or confided in men more than I did in these. They were as true as steel, and no band of brothers could be more loving. There were no mean advantages taken of each other, no tattling, no giving each other ban names to Mr. Freeland, and no elevating one at the expense of the other. We never undertook anything of any importance which was likely to affect each other, without mutual consultation. We were generally a unit, and moved together.” (Douglass & Ruffin, 2001) Lussana’s (2016) narrative explains that the above testimonial from the Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, is an illustration of the importance that friendship has played in the lives of African American men’s lives throughout the duration of their experience in the American context. Enslaved Black males created their own all male social network and subculture of brotherhood. In these circles recognized their interdependence and formed all male networks of cooperation, masculine identity construction, and resistance (Lussana, 2016). Therefore, they had to form friendships under duress and surveillance. Often, they covertly met with one another to spread news of rebellion, or even drink, gamble, and organize social events (Lussana, 2016). During slavery, Black males’ friendships provided them: “hope, comfort, and relief from the drudgery and horrors of their enslavement” (Lussana, 2016, p.99). Male friendships were critical during slavery, as they trusted one another to share their conspiratorial thoughts and nurture their opposition to slavery. Afterall, running away during slavery was a gendered form of resistance, with the vast majority of escapees being Black males (Lussana, 2016). Trust and loyalty were excessively central to Black male friendships given that the consequences of sharing their thoughts, plans, or generally unsanctioned activities could be fatal. Other males were a buffer against oppression (Lussana, 2016). Henry Brown, a fugitive from enslavement said this about the importance of friendship: “we love our friends more than White people love theirs, for we risk more to save them from suffering. Many of our number who have escaped from bondage ourselves, have jeopardized our own liberty, in order to release our friends, and sometimes we have been retaken and made slaves again, while endeavoring to rescue our friends from slavery’s iron jaws” (Brown & Ernest, 2008, p.34). Brown adds that: “A slave’s friends are all he possesses that is of value to him. He cannot read, he has no property, he cannot be a teacher of truth, or a politician; he cannot be very religious, and all that remains to him, aside from the hope of freedom, that ever present deity, forever inspiring him in his most terrible hours of despair, ,is the society of his friends.” (Brown & Ernest, 2008, p.34) Enslaved parents taught their children to refer to other enslaved Blacks as brother and sister to instill in them the principle that they were a part of a community that was responsible for them and vice versa (Mintz, 2004, p. 26). Enslaved Blacks preferred to refer to one another as ““bro” and “Sis” rather than “nigger”” (Roberts, 1989, p. 181). After slavery, Black male friendships were continued in formal men’s clubs, fraternal lodges, political parties, and businesses. Before enslavement, in African societies there were typically formalized rites of passage that fostered the formation of male friendships, starting in adolescence (Lussana, 2016). Male rituals consisting of learning activities, trials, and tests that they struggled through together were expected to draw them together into lifelong relationships. As Franklin (2004) explains, African American models of friendship are extensions of African manhood rituals and the relationships formed between unrelated African men from of different ethnic groups during slavery. Lussana’s (2016) work challenges the notions that Black men were emasculated, unable to provide for families, or unable to form lasting bonds. This text also makes it clear that Black men did not cease to implement rites and rituals to shape the development of manhood for one another. Perhaps, more critical is that the text makes the point that Black manhood is not only defined by Black men’s relationships to women, but their relationships to their brethren. Lussana (2016) interrogates many original sources, including autobiographies and other narratives from enslaved Black men and women’s narratives about the enslaved men in their lives. The author explains several aspects of Black men’s experiences with one another including: their work; their leisure activities; their collective resistance with other males; their friendships with one another; and their methods of communicating information and subversive plans with one other across plantations. Different African rites and rituals around manhood are firmly established as a point of reference for Lussana (2016). The author makes strong connections between the interaction between the cultural interactions between African men and those of men of African descent during enslavement. However, his analysis remains primarily focussed on similar behaviors and practices. Here, the author misses an opportunity to highlight the continuities and discontinuities of African worldviews (values, beliefs, and philosophies of manhood) in the American context. These invisible aspects of culture do not receive a great deal of voice in Lussana’s (2016) explanation of the relationships between African manhood on the African continent and in the American antebellum south. This text, remains one of the only explicitly gendered analysis of Black male relationships during slavery. The multidimensionality that Lussana’s analysis offers is a leap in the direction of producing humanizing work on Black men’s lives beyond the culture of poverty and oppression. Contemporary Relevance Peer friends provide young males with their basic needs for intimacy, belongingness, the development of social skills, and excitement. These relationships provide Black males a safe zone within which they can be themselves (Bonner, 2014). They rebel against social norms, learn and set trends with one another. They are often on the cusp of cultural creation, spurred on by a validation from their peers that they would not get from their elder. For example, Afrika Baby Bambataa of the Jungle Brothers arguably one of most influential hip hop groups said: "The school talent shows are a tradition. It's just that when we came on the scene, we added something new to the tradition, which was hip hop. Here’s a stage where we could do something that ninety percent of our peers know what we’re doing but our elders don’t. We can get on the mic and we can perform our lyrics and be just stars in the high school." (Ogg, & Upshal, 1999, p. 105) Today, peer relationships remain critical for Black males. Because peer relationships are usually between equals, they provide a sense of closeness and relatedness that cannot be achieved in parent-child relationships. Although peers may have more short-term influence on peer behavior, parents still have more influence on long term behavior (such as attending college) (Davies & Kandel, 1981; Belgrave & Brevard, 2014). It is critical for parents and young Black men to recognize the heritage of brotherhood and the role that it has played in sustaining Black family and community. It is also important that Black communities draw on Africa rites, and African American rites of passage to construct culturally aligned, institutions, and processes that allow Black males to come together to form bonds around values that advance the agenda of Black collective emancipation. Brown, H. & Ernest, J. (2008). Narrative of the life of Henry Box Brown, written by himself. University of North Carolina Press. Douglass, F., Ruffin, G. (2001). The life and times of Frederick Douglass. Scituate, Mass.: Digital Scanning. Lussana, S. (2016). My brother slaves: Friendship, masculinity, and resistance in the antebellum south. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. Mazama, A. (2009). Rites of passage. In M.K. Asante & A. Mazama, Encyclopedia of African religion. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE, pp. 570-574. Written by Serie McDougal

Are there certain family and environmental experiences during childhood that effect Black men’s romantic relationships as adults? This topics sparks curiosity for many reasons, including, but certainly not limited to both positive and negative relationship experiences, marriage rates, and divorce rates. A brand new study has been published by Kogan, Yu & Brown (2016). They investigated the effects of childhood family and socio-environmental factors on the relationship commitment behavior of adult African American males. They used data from a panel study which interviewed 315 African American male youth, in addition to their primary care givers and 5th grade teachers. The males were interviewed from age 11 to 21. The researchers hypothesized that poor social environmental contexts such as poverty, would lead to harsh parenting, which would then lead to anger and poor emotional regulation among the Black male youth. Finally, this anger would lead to poor relationship commitment behavior. What They Found Kogan, Yu & Brown (2016) found that parents who were unemployed, low income, and single-parent headed, were more likely to include hitting, slapping, and shouting in their disciplinary strategies. The young males who experienced more of this kind of parenting were more likely to report anger in their mid-adolescence (13-15 years old). Anger was a key factor linking harsh parenting and commitment behavior. Those who experienced more anger were less likely to have supportive, committed, and secure quality romantic relationships. Anger from...? If anger is the key element, then where does it come from? It is important to note that in this study, for young men who reported more experiences with racism, harsh parenting was more likely to lead to anger. For those who reported little experience with racism, harsh parenting didn’t lead to mid adolescent anger. Prevention Based on the findings of studies like this one, it is important to provide youth with supportive environments and programs that help them to psychologically process and socially resist racism. Moreover, Kogan, Yu & Brown (2016) suggests that social programs that target parenting practices, by encouraging nurturing disciplinary approaches. They also raise the issue of the importance of racial socialization, or teaching Black youth what it means to be Black, knowledge about the history and cultures of Black people, and preparation for racial experiences. What to Make of the Study This study was conducted on a disproportionately poor sample. Harsh parenting might be less prevalent among a sample that was more representative of the Black community. Moreover, 21 years of age, the age at which this last phase of data was collected, is not quite adulthood, but what the researchers refer to as “emerging adulthood”. Because of this, there is likely to be a fair amount of maturation in the men’s relationship skills that would still be developing. Give the importance of racism in this study for young Black males in mid adolescence, it is likely to be a factor for their caregivers as well. However, based on the data collected we don’t know much about how racism effected the parents. Future research would be enriched by looking at the effects of racial discrimination on parenting. Lastly, the study is clearly geared toward identifying or predicting negative outcomes. More diverse samples in future studies might help research in this area move away from the risk factor orientation that guides much of the current research on Black males. Ultimately, this study raises some very important issues about racism and its amplification of stress on the relationships between Black people that must be mitigated to enhance the Black world. Works Cited Kogan, S., Yu, T. & Brown, G. (2016). Romantic relationship commitment behavior among emerging adult African American men. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(4), 996-1012. Written by Serie McDougal III

Recently Raja Staggers-Hakim (2016) wrote an article called The Nation’s Unprotected Children and the Ghost of Mike Brown, or the Impact of National Police Killings on the Health and Social Development of African American Boys. Here he discusses the impact of national police brutality cases and extrajudicial killings on the social development, mental health, and overall wellbeing of young African American males. Staggers-Hakim (2016) also discusses recommendations for social policies. With new investigations of police-induced trauma, researchers tend to want to move toward discussing solutions—which is no doubt important. However, there are very few investigations that move beyond discussing the need for solutions such as healing, to actually explaining the very processes for healing. It is well known that the continuous experience of racism can lead to symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (emotional stress, physical harm, and fear). Evans, Hemmings, Burkhalter, & Lacy (2016) do more than merely explain post-traumatic stress disorder, and propose a process for guiding Black males toward post traumatic growth (PTG). According to these researchers, PTG can be achieved through strategies incorporated into the provision of counseling services. PTG is defined as an individual’s experience of positive change and resiliency following a traumatic life event (Evans, Hemmings, Burkhalter, & Lacy, 2016). Research tends to focus on the devastating consequences racial trauma, although between 30 and 90 percent of people who experience trauma experience positive growth and change (Evans, Hemmings, Burkhalter, & Lacy, 2016). 2007). Evans, Hemmings, Burkhalter, & Lacy (2016) present a number of specific recommendations for providing culturally sensitive PTG treatment for working with African American men who have experienced race-based trauma:

Works Cited Evans, A. M., Hemmings, C., Burkhalter, C., & Lacy, V. (2016). Responding to race related trauma: Counseling and research recommendations to promote post-traumatic growth when counseling African American males. Journal of Counselor Preparation & Supervision, 8(1), 78- 103. Staggers-Hakim, R. (2016). The nation’s unprotected children and the ghost of Mike Brown, or the impact of national police killings on the health and social development of African American boys. Journal of Human Behavior in The Social Environment, 26. Written by Serie McDougal

Globalization increases the likelihood of diverse human interactions in the full range of societies’ institutions. Therefore, the threat of cultural bias is likely to continue to challenge validity in the research. Assumptions of universal validity are increasingly in doubt in light of cultural variation (Persson, 2012). Increased interaction between people of diverse cultural backgrounds, not only makes cultural sensitivity critical to the research process, but cultural competence has become all the more imperative. Given the fluid nature of culture, cultural competence is an ongoing process of self- reflection, learning, and relearning one’s own cultural position and those of populations of study. It is also the ability to engage in the research process in ways that affirm the cultures and contexts of the people being studied. In the interest of improving human service providing, economic and political initiatives, sometimes emphasize the utilitarian and practical value of research (Persson, 2012). However, this is often done to the exclusion of culture and the ways that culture can change how effective an initiative is from one context to the next. Although most evaluations of validity focus on the validity of tests and measurements (construct validity) (Hardin, Robitschek, Flores, Navarro & Ashton, 2014), cultural validity is relevant at every step of the research process. Scientific communities, themselves, can be thought of as subcultures. Moreover, the researchers within them, knowingly and unknowingly, bring their own values and assumptions into the research process. This starts with the choice of what to research and the formulation of research questions. When choosing topics that are interesting and intriguing to the researcher, it is important to investigate how research questions relate to the needs and concerns of the population(s) being studied and how their priorities might be integrated into the research process, if necessary. Hardin, Robitschek, Flores, Navarro & Ashton (2014) explain how important it is for the researcher to consider how the central concepts being research have been defined in the past, and how they have been operationalized and evaluated. Researches must also investigate what groups these concepts derived from, what groups they have been applied to, and what results have shown. This forces the researcher to identify the specific cultural contexts from which their concepts of interest emerged, a prerequisite for identifying important differences in other contexts (Hardin, Robitschek, Flores, Navarro & Ashton, 2014). It is critical for the researcher to interrogate the ways that culture may influence the meaning of the central concepts being studied or theories being tested. The meaning of a concept in one culture may differ greatly or slightly from one cultural context to the next. An evaluation of culture specific literature may provide insight about how concepts are construed in the cultures being studied and how they might be relevant to the research process. However, researchers should note that the volume of research on their topics might be skewed by country and academic discipline. Countries and academic disciplines carry their own cultural variations. Bias in literature from value laden disciplines may make it difficult to find literature that privileges the cultural perspectives of the people being studied. In these cases, it is important to target academic disciplines that focus on ethnic specific investigation or research that comes from the cultures being studied. Preliminary interviews with populations of interest, can give the researcher a sense of how concepts are being construed in different or similar ways. It is important that the people being studied have an opportunity to have their realities investigated in ways that reflect the nuances of how they experience and understand phenomena on their own terms. The same process can be applied to testing theories. Theories are not value-neutral, and should be evaluated for culturally embedded assumptions (Persson, 2012). Many mainstream theories (models or frameworks) have been normed on racially/ethnically homogeneous samples. Those theories are often the more popular and easily identifiable ones. However, for this researcher this means specifically seeking out culture specific theories when they are available (Persson, 2012). It is critical to formulate and/or reevaluate research topics and questions in light of information gained from taking the aforementioned steps (Hardin, Robitschek, Flores, Navarro & Ashton, 2014). When using non-culture specific quantitative measures or assessments, it is critical to avoid assuming their universal applicability. The researcher must statistically assess their validity where applied to different cultural groups, adding or removing items and dimensions where necessary. The choice of methods of data collection should be informed by the unique cultures and contexts of the sample being investigated. Cultural bias may also enter the process of making sense of, or interpreting the results of research investigations. Because of this, it is often helpful to consult stakeholder or target populations in the interpretations of results to ensure that multiple perspectives are considered. Lastly, it is critical to report the results of research in ways that help allow data to be used to improve the lives of target populations. Works Cited Hardin, E. , Robitschek, C. , Flores, L. , Navarro, R. & Ashton, M. (2014). The cultural lens approach to evaluating cultural validity of psychological theory. American Psychologist, 69(7), 656-668. Persson, R. (2012). Cultural variation and dominance in a globalised knowledge-economy: Towards a culture-sensitive research paradigm in the science of giftedness. Gifted and Talented International, 27(1), 15-48. Written by Sureshi Jayawardene

Youth suicide is a major public health issue in the United States. A 2015 study published in JAMA Pediatrics noted that suicide was the second leading cause of death among adolescents aged 12-19. Suicide accounts for more deaths in this age group than cancer, influenza, heart disease, diabetes, HIV, stroke, and pneumonia combined. Suicide and Black Youth Suicide rates among Blacks have typically been lower in all age groups compared with Whites. However, this study showed a steep rise in suicide among Black children, from 1.36 per one million to 2.54 per one million children—more than double since the 1990s (Bridge et al, 2015). This rate was also significantly higher than the rate among White children, which had declined from 1.14 per one million children to 0.77 (Bridge et al, 2015). Researchers noted that it was the first time a national study found a higher suicide rate for Blacks than for Whites (Bridge et al, 2015). They used national data based on death certificates that listed suicide as the cause of death. Researchers in this study offered some explanations for this stark difference: that Black children are exposed to greater violence and traumatic stress; and that Black children are more likely to experience early onset of puberty which can lead to a higher risk of depression and impulsive aggression (Bridge et al, 2015). However, there was no indication as to how these characteristics had changed during the period of the study and if they alone were sufficient to explain the sharp rise in the Black youth suicide rate. Additionally, gun deaths for Black boys remained the same while suicide by hanging had more than tripled (Bridge et al, 2015). For White boys, on the other hand, gun deaths fell by about half and suicide by hanging remained the same. Researchers surmised that access to guns might be greater among Black boys while gun safety education may not be reaching them (Bridge et al, 2015). Traditionally lower suicide rates among Blacks were explained as the result of protective factors such as strong social networks, family support, religious faith, and other cultural influences. Given the sharp change in suicide among Black children since the 1990s, the researchers in this study questioned the strength of these protective factors in curbing suicide (Bridge et al, 2015). Culturally Relevant Interventions for Suicide Prevention In a recently published study, Robinson et al (2016) explain that suicide is one of the most pressing issues facing Black youth today—one that has become more prevalent in the last 20 years, but remains largely overlooked. According to the CDC, documented suicide is the third leading cause of death for African Americans ages 15-24. However, Robinson et al (2016) caution that: 1) suicide rates among Black adolescents may be underreported or misclassified due to cultural stigma and; 2) subject-precipitated homicides and “suicide-by-cop” may contribute to the high volume of undetermined suicide intent classifications. Suicide-by-cop is when a person deliberately acts in a threatening manner to provoke a lethal response from a law enforcement officer. Nonetheless, the need for effective prevention interventions is extremely high. Moreover, Robinson et al (2016) call for culturally grounded suicide prevention programs that are designed to address the complexity of psychosocial stressors facing African American youth. These stressors include: developmental changes, racial discrimination, and resource poor living environments (Robinson et al, 2016). Poverty is also linked to chronic stress and suicidality (Robinson et al, 2016). Particularly for young Black males, these conditions are more likely to result in suicide (Robinson et al, 2016). Culturally Adapting the Adolescent Coping with Stress Course Black youth are already one of the most vulnerable populations in the nation, regularly threatened by different types of violence and trauma. These youths are also three times more likely to grow up in resource poor neighborhoods than any other ethnic group in the US (US Census Bureau, 2014). Robinson et al (2016) noted that there are few school-based suicide prevention programs that are culturally grounded for African American adolescents. Their study culturally adapted Clarke and Lewinson’s (1995) empirically validated Adolescent Coping with Stress Course (CWS), representing “a synthesis of culturally specific contextual material” (p. 119-120). The researchers maintained the original length of the CWS (15 sessions of 45 minutes each) and the theoretical framework (multifactorial approach that included identifying feelings and expressions of stress, reducing negative cognitions and increasing positive thoughts, acknowledging and identifying risk factors for stress, and developing and enhancing personal competencies for coping with stress). However, they incorporated substantive cultural, structural and environmental adaptations to Clarke and Lewinson’s (1995) original program in the following ways:

Preliminary Findings of a Culturally Grounded Intervention A-CWS was implemented at four public high schools in a large Midwestern metropolitan area with a predominantly African American student body and each of these schools had an on-site student-based health center. The schools also reported dropout rates between 24% and 31%, compared with the city-wide rate of 16%. Participants in the study were 9th, 10th, and 11th grade students (a total of 758) who were mostly African American (91%) and female (60%). All participants qualified for free or reduced lunches based on family income. The participation rate was 73% and highest for 9th graders and lowest for 11th graders, who, after age 16, are not legally required to attend school. Researchers analyzed only the responses of the African American study participants (N=686) and of them, 682 completed the suicidality measure and almost half (N=330) reported some level of suicide risk. Female students overrepresented the entire sample (n=416, compared to n=266 for males) as well as all levels of risk (i.e., low, moderate, high). The researchers found that students who participated in the A-CWS evidenced an 86% relative suicide risk reduction at posttest, compared to youth in the standard care control group who displayed similar risk at pretest. This is significant and supports the many arguments Black psychologists (Myers and Speight, 2010; Goddard, 1993; Nobles and Goddard, 2015; Nobles and Goddard, 1977) in particular have made in favor of culturally relevant solutions to issues in the Black community. Indeed, more intervention strategies that address African American stress reduction need designing and testing to address the glaring problems of suicide in Black communities. Robinson et al (2016) also recommend future studies examine causal links between individual and ecological variables that lead to suicide among Black youth. Works Cited Bridge, J. A., Asti, L., Horowitz, L. M., Greenhouse, J. B., Fontanella, C. A., Sheftall, A. H., & Campo, J. V. (2015). Suicide trends among elementary school–aged children in the united states from 1993 to 2012. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(7): 673-677. Goddard, L. L. (1993). An African-Centered Model of Prevention for African-American Youth at High Risk. Myers, L. J., & Speight, S. L. (2010). Reframing mental health and psychological well-being among persons of African descent: Africana/black psychology meeting the challenges of fractured social and cultural realities.The Journal of pan African studies, 3(8). Nobles, W. W., & Goddard, L. L. (2015). An African-Centered Model of Prevention for African- American Youth cat High Risk. REPORT NO CASP-TR-6; DHHS-(SMA) 93-2015, 115. Nobles, W. W., & Goddard, L. L. (1977). Consciousness, adaptability and coping strategies: Socio-Economic characteristics and ecological issues in Black families. The Western Journal of Black Studies, 1(2), 105. Robinson, W.L., Whipple, C.R., Lopez-Tamayo, R., Case, M.H., Gooden, A.S., Lambert, S.F., and Jason, L.A. (2016). Culturally grounded stress reduction and suicide prevention for African American adolescents. Practice Innovations 1(2): 117-128. |

Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed