|

Written by Serie McDougal and Sureshi Jayawardene

Recently, Shaun Harper and Isaiah Simmons of the Race and Equity Center at the University of Southern California authored a 50-state report card assessing the status of Black students at 506 individual public colleges and universities. They made this assessment using four “equity indicators” to essentially grade public colleges and universities and ultimately assign them an equity index score similar to a grade point average. Harper and Simmons (2019) note that there are more than 900,000 Black undergraduates enrolled at public colleges and universities across the US. That’s more than 900,000 Black undergraduates whose education and future lives are impacted by the educational environments they experience. As we know, for African Americans, inequities are not such forces that are easily overcome, but tend to have long-lasting and even intergenerational effects. Keeping this figure of Black undergraduates in the nation at the forefront of our minds is important as we consider the utility of Harper and Simmons’s (2019) report card and the equity index scores. For instance, these scores can be useful for individual public institutions of higher education in their strategic planning around diversity, equity, and inclusion, especially as they design programs and policies to support the equitable education, attainment, and retention of their Black student populations. They can be useful for faculty who teach, mentor, advise, and conduct research with Black undergraduates. These scores are equally important for Black families exploring the best and most competitive higher education opportunities for their students. Harper and Simmons (2019) note, their approach to scoring these institutions is predicated on making “inequities more transparent and to equip anyone concerned about enrollment, success, and college completion rates for Black students with numbers they can use to demand corrective policies and institutional actions” (p.3). The four equity measures highlight evidence of the presence or absence of equity in key areas: representation, gender, degree completion, and Black student-to-Black faculty ratio. Among their major findings, Harper and Simmons (2019) found that Black students are under-enrolled relative to their population in their specific states in three-fourths of the institutions. Also, only 39.4% of Black students completed their bachelor’s degrees compared to 50.6% of undergraduates overall. A finding that stands out as exceptional, yet not surprising, is that there was a ratio of 42 Black students to every Black faculty member and 40 of the institutions employed no full-time Black faculty. This stands out not only as a finding but as a measure of equity as well. It is important that future measures of equity include this ratio given the significance of the presence of Black faculty for Black students. The presence of Black faculty is directly related to Black student success because their presence is positively related to Black graduate and professional students’ rates of enrollment and graduation. However, Black faculty are challenged by the need to work with students within and outside of their academic disciplines and they must also contend with racism, isolation, and being overburdened by responsibilities on college campuses (Pulliam & McGregory, 2009). Another highlight of this report is that across all 506 institutions, the average Equity Index Score was 2.02. The authors further indicate that no institution received above 3.50. Of the 506 institutions assessed, 200 earned scores below 2.00. This is important information for parents and students especially, because it highlights how persistent educational inequity may be in their home states and the educational opportunities therein. While this information is not new to African American communities who have resisted educational constraints and barriers for generations, Harper and Simmons’s (2019) report gives us clearer portraits of the actual areas in which these public universities and colleges are inequitable for our children. Finally, Harper and Simmons (2019) caution that their findings should not be used to reinforce deficit narratives about Black students and their achievements and aspirations. Rather, they urge readers, educators, universities, and policymakers to use the data to better understand how systems and structures uphold inequities Black students face and compel them to implement correctives. You can read and/or download the report here and see specific and detailed information for the equity indicators for each institution and within each state. Works Cited Harper, S. R., & Simmons, I. (2019). Black students at public colleges and universities: A 50-state report card. Los Angeles: University of Southern California, Race and Equity Center. Pulliam, R.L. & McGregory, R.C. (2009). In pursuit of African American males as scholars: Prescriptive viewpoints. In T.H. Frierson, J.H. Wyche & W. Pearson, Black American males in higher education: Research, programs, and academe (pp. 331-355). Bingley: Emerald.

0 Comments

Written by Serie McDougal

“When are America catches a cold, Black America catches the flu”. Many people are familiar with quotes like these which reinforce the notion that socio-economic suffering is not distributed equally across race in the American context. What’s more, the suggestion is that African Americans typically absorb an excess impact of national dilemmas across social arenas including but not limited to healthcare, criminal justice, employment, etc. Diette, Goldsmith, Hamilton, & Darity (2018) conducted a study to answer the question; does experiencing unemployment damage the psychological wellbeing of Black people more than Whites. Why is this an interesting question? Among social sciences, there is the idea that Black people may be more resilient to the suffering associated with unemployment based on the logic that they were used to higher levels of structural discrimination. From another perspective, these notions are rooted in age-old racist myths like those that emerged from the physical abuse during enslavement. For example, the notion that Black people could absorb more pain than Whites, as a way to justify the brutality inflicted on them. Nevertheless, to answer their question, Diette, Goldsmith, Hamilton, & Darity (2018) used data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. They found that Black people who experience short-term unemployment were significantly more likely to suffer from psychological distress compared to Whites who also experienced short-term unemployment. It is clear that during the Great Recession, rose as high as 15.9%. Thus Diette, Goldsmith, Hamilton, & Darity (2018) infer from their results that Black people likely absorbed a disproportionate psychological cost as a result, compared to Whites. They found little statistical difference in Black and White reactions to long-term unemployment. The explanation for why short-term unemployment has this differential effect is centered around wealth. Job loss is associated with feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and prolonged sadness. This is because when a job is lost a person must contend with paying utilities, putting food on the table, and paying their rent (Akee, 2018). However, these things are more of a struggle when a person does not possess access to the kind of wealth that can help them pay for these things when they are unemployed. In short, wealth is a buffer against the concerns associated with short-term unemployment. Thus people with more wealth are more protected from the psychological distress associated with unemployment compared to those who have less wealth; and White Americans had 10-times the median wealth possessed by Black Americans in 2016 (Akee, 2018). What should be done with this data? Proposed include reparations, homeownership programs, higher income levels, baby bonds, individual development accounts, policies to treat distress for the unemployed, reemployment programs, and more expansive safety nets for the unemployed (Akee, 2018; Diette, Goldsmith, Hamilton, & Darity, 2018). What the analysis of these results misses is the role of anti-Blackness intergenerationally and contemporarily. Conversations around fail to account for this spurious variable routinely which has strong implications for potential solutions. Because it was enslavement and systematic anti-Black which led to this wealth gap and help to maintain it. Institutionalized policies such as those mentioned above will likely fail without oversight bodies. Moreover, the disproportionate impact absorbed by African Americans is an incentive to continue their disproportionate suffering because the trends reduce the impact economic downturns might have on non-Blacks. Works Cited Akee, R. (2018, August 22). New evidence that losing your job is even more stressful for black Americans. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/new-evidence-that-losing-your-job-is-even-more-stressful-for-black-americans/?utm_campaign=Economic Studies&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=65503971 Diette, T. M., Goldsmith, A. H., Hamilton, D., & Darity, W. (2018). Race, Unemployment, and Mental Health in the USA: What Can We Infer About the Psychological Cost of the Great Recession Across Racial Groups?. Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy, 1-17. Written by Serie McDougal III

In Ebonics, the word son can have multiple meanings. It can refer to a friend, someone who a speaker does not know, and it can be used to talk down to someone or refer to dominating someone. However, the word can also be used as a verb to refer to the act of teaching another person. Put simply, the meaning of the word son in Ebonics can change radically depending on the context in which it is used. A recent article written by Jay-Paul Hinds (2018) asserts that sonship is a lifelong experience that can help men to overcome feelings of inadequacy that come from troubled relationships with their fathers. Hinds’ (2018) primary argument is that sonship should not be viewed negatively for men, and that they should be allowed to search for male figures and assume the role of son even in adulthood. For Hinds, the desire to be another man’s sons should be cultivated responsibly so that it is not associated with shame. Hines (2018) uses the examples of Martin Luther King Sr. and Martin Luther King, Jr. as examples of men who experienced strained relationships with their fathers and stood to benefit from being able to assume sonship as adults. A challenge in Hinds’ (2018) work is that he seems to imply that seeking a father figure outside of one’s biological father requires there to be some problems in the father-son relationship. Looking at pre-colonial African family systems demonstrates that father was a designation that as not limited to biological fathers. In fact, manhood rites were guided by elders who boys were expected to treat as authority figures and look to for guidance. As men they were expected to look to these men for wisdom as elders. The need for what Hines (2018) refers to as sonship was anticipated by African cultures. However, these communities of lifelong fathers are necessary today because biological fathers may experience parental alcohol/drug abuse, teen pregnancy, parental incarceration, homelessness, domestic violence, physical illness, emotional instability, neglect/abandonment, poverty, and parental death (Smith, 2010). However, communities of fathers are not only necessary because of parental inadequacy but because they surround children with men who may serve as models and resources that no single father could provide alone. Hines (2018) argues for removing shame from the act of seeking sonship. A different conversation should involve removing suspicion from Black men who assume fatherly roles to young males who are not their biological sons. Works Cited Hinds, J. (2018). The Son’s Fault: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Search for and Recovery of Sonship. Journal Of Religion & Health, 57(2), 451-469. Smith, A. (2010a). Standing in the “GAP”: The kinship care role of the invisible Black grandfather. In R.L. Coles & C. Green (Eds.), The Myth of the Missing Black Father. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 170-191. Written by Serie McDougal

Job training programs provide two essential services: 1. Skills that are aligned with employment opportunities, 2. Link trained job seekers with job placement (NUPI, 2012). The National Urban League (2011) proposes the authorization of the Workforce Investment Act, to increase national investment in the re-training of workers for 21st-century jobs. This kind of training can be targeted toward less educated workers who lost their jobs in the great recession. This way, Black males could gain the skills necessary to benefit from new job growth. The dramatic increase in demand for H1b visas by U.S. companies in the 1990s is evidence of the failure to invest in the educational development of domestic youth, especially African Americans (Hardy & Buckner, 2011). This is significant given that jobs that require a post-secondary education have been projected to increase faster than jobs requiring a high school diploma or less between 2012 and 2022 (Burns, 2014; Johnson & Shelton, 2014). Some cities, like Baltimore, have established job hubs that serve high numbers of African Americans, providing them with professional training, job search and resume assistance, and digital resources (Rawlings-Blake, 2014). Bryant (2013) explains the role of the non-profit called Operation Hope, which provides underserved communities with financial literacy empowerment and entrepreneurial training. Operation Hope has helped people open bank accounts, raise their credit scores, with the goal of changing their lives and communities. In response to the high-profile police killing of Michael Brown, a young African American male, the Saint Louis affiliate of the National Urban League, developed the Save Our Sons Workforce Development Program (SOS). The program is focused on helping African American males find viable employment (McMillan, 2016). The major tenants of the four-week program are 1. How to find a job, 2. How to keep a job, 3. How to get promoted, and 4. How to remain marketable in the workplace (McMillan, 2016). The program has helped hundreds of men find jobs, 55% of whom had prior felony convictions (McMillan, 2016). Intermediaries Intermediaries can also help in a workforce development capacity. Nightingale (2010) identifies two types of workforce development intermediaries: 1. labor exchange services intermediaries (LESI), and 2. Institutional or administrative intermediaries (IAI). LESIs are programs, companies, and organizations, or persons that act as a link between job seekers and employers. IAIs are programs, companies, agencies, or organizations that act on behalf of government agencies, usually under contract, to provide labor exchange services or other employment-related services to clients seeking employment (Nightingale, 2010). Black communities can create their own intermediaries through neighborhood job clubs, and organizations to share wisdom about financial literacy, and managing personal resources (The Covenant with Black America, 2006). The development of independent Black community run intermediaries may offer essential local, culturally relevant services to supplement other job services. Job Creation and Training in Targeted Industries Some argue that government intervention is often necessary because poor Blacks are significantly vulnerable to structural changes in the economy like the shift from manufacturing to the service industry. While in the 1980s 42% of newly created jobs were in the service industry, in the 1990s 53% were (Holzer & Offner, 2006). The Urban League has long advocated that job creation funding should be distributed nationally giving priority to places with the highest unemployment, particularly targeting the long-term unemployed (Morial, Wilson, Richardson & Clark, 2010). The National Urban League proposes the creation of jobs and training of urban residents in several key areas: technology, through the funding of grants, business incubators, and technology training sites to foster business growth; health care, through recruiting, training, and hiring urban residents as nurses, physicians’ assistants, etc.; manufacturing jobs, by using financial incentives to promoting the purchase of American manufacturing goods; urban infrastructure, by increasing the number of railroad projects, urban water systems maintenance, expansion of parks, public buildings, and schools in under-served neighborhoods, and ; clean energy jobs, by giving tax deductions for clean energy companies to invest in urban area programs to improve the energy efficiency of buildings (NUL, 2011). Urban infrastructure jobs might also include training of inner city youth to install, repair, and maintain new sustainable electronic equipment and appliances in homes and businesses (Dodd, 2009). In addition, other much-needed projects including the rebuilding of American bridges and modernizing the country’s electrical grids (Dodd, 2009). These infrastructure jobs would increase the overall unemployment rate, and a 1% decline in the overall unemployment rate is associated with a 15.4% decline in the African American male unemployment rate (Rodgers, 2009). Some propose comprehensive neighborhood revitalization efforts that coordinated, government-funded efforts to develop initiatives such as, Choice and Promise Neighborhoods, Promise Zones, and the Strong Cities, Strong Communities initiatives. Conservative politicians usually rally against such place-based initiatives. Solutions for Youth Employment Youth Opportunity Grants provide funding for programs that provide community-based youth development strategies could provide opportunities could provide opportunities for job training programs (Nightingale & Sorenson, 2006). However, because of the urgency of employment, many young Black men miss school for work. Nightingale & Sorenson (2006) point out that job training programs may not be the best solution for some youth. Because of the immediacy of their own and their families’ financial states, they are more interested in immediate employment than job training (Nightingale & Sorenson, 2006). For these young men, on the job training opportunities may be better suited to benefit them; in these programs, they would receive an hourly wage while training (Nightingale & Sorenson, 2006). Particularly effective for Black males would be an increase in programs that provide subsidies for employers who provide targeted groups (underrepresented ethnic groups) with on-the-job training (Johnson & Shelton, 2014). These programs have been shown to positively affect employment and earnings among those who are 18 and older (Johnson & Shelton, 2014). In addition, job search programs have proven effective for participants. Between 1993 and 1998 youth job training funding was reduced and shifted to training for dislocated workers (few of whom were young adults) (Nightingale & Sorenson, 2006). Dislocated workers are defined as:

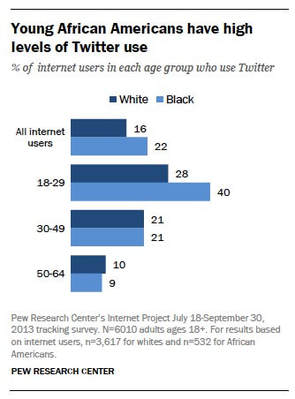

Preparation for New Job Market From George Washington Carver’s agricultural science to Charles Drew’s lifesaving medical work, Black men have made important contributions to human society in the areas of advanced technologies. New jobs will require higher skills than in the past, even blue-collar jobs that once employed low skilled workers will require training in science, technology, engineering, and math (Rawlings-Blake, 2014). African Americans must be a part of the transition into a knowledge-based, technology-driven economy (Marshall, 2013). Black men will need to draw upon their legacy of science and technology to thrive and uplift the Black community in a changing economy. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are over 122,000 high paying jobs per-year that require a computer science bachelor’s degree, but American colleges and universities only graduate 40,000 students with a bachelor’s degree in computer science (Humphries, 2013). It is important for youth to be trained to assume jobs in the emerging job market that will include growing number of STEM jobs in the next decade (Moore, Flowers & Flowers, 2014). This is critical given that African Americans are 13% of the population of the U.S. yet, only 6% of the STEM workforce (Moore, Flowers & Flowers, 2014). African Americans’ share of the scientific workforce was 7.4% in 2000 and decreased to 6.5 in 2010 (Sharpe, 2011). African Americans are underrepresented in the STEM workforce due to educational inequities, which hinders them from competing for jobs that require STEM skills (Sharpe, 2011). According to some, African Americans must overcome their particular aversion to STEM fields (Shepherd, 2014). Sharpe (2011) suggests that preconceptions about African American students’ interests are false because evidence suggests that their Black college students have been found to have a greater interest in STEM disciplines than their White counterparts. The interest in majoring in STEM disciplines among African American youth is actually increasing (Sharpe, 2011). However, it is true that many of them switch majors after under-performing or having poor interactions with faculty, which suggests that they need greater preparation for STEM fields before reaching college. Moreover, educational institutions need to be better prepared to teach and interact with Black students in culturally relevant ways. Between 1998 and 2008, the cumulative number of STEM degrees earned by Black women exceeds those earned by Black men, although Black men earned nearly twice as many degrees in engineering as Black women (Sharpe, 2011). The national Department of Energy launched the Minority Serving Institution Partnership in 2012 which has provided $4 million in research grants to over 20 HBCUs giving them access to the Department’s resources. The objective of the program is to give them access to technology to increase interest in STEM fields (Harris, 2013). Other programs like the Mickey Leland Energy Fellowship is a ten-week internship providing minority and female STEM students who want to work on fossil fuel challenges with the Department of Energy (Harris, 2013). In the private sector, AT&T for example, launched Project Velocity IP to expand wired and wireless internet access to under-served communities (Marshall, 2013). However, there must be programs that are targeted opportunities for Black males. Government funded and supported job creation and training strategies are ultimately necessary yet insufficient. Difficulties in seeking such support are inherent because supporting Black male economic power will imminently undermine White privilege. Thus, Black male economic empowerment but built on a coupling of government supported initiatives and independent Black institution building and the growth of Black-owned businesses. Works Cited Bryant, J.H. (2013). Financial dignity in an economic age. In National Urban League (NUL), The State of Black America: Redeem the dream. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp. 134-139. Burns, U.M. (2014). Leaving no brains behind. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America. Transaction Publishers, pp. 152-156. Dodd, C.J. (2009). Infrastructure and job creation. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: Message to the president. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp.101-108. Hardy, C.P. & Buckner, M. (2011). Leveraging the greening of America to strengthen the workforce development system. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America. Transaction Publishers, pp. 76-83. Harris, D. (2013). Diversity in STEM: An economic imperative. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: Redeem the dream. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp. 92-95. Holzer, H.J. & Offner, P. (2006). Trends in the Employment outcomes of young Black men, 1979-2000. In R.G. Majors and J.U. Gordon (Eds.), The American Black male. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers, pp. 11-37. Humphries, F.S. (2013). The national talent strategy: Ideas to secure U.S. competitiveness and economic growth. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: Redeem the dream. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp. 86-91. Johnson, B. & Shelton, J. (2014). My brother’s keeper task force report to the president. White House: Washington D.C. Marshall, C. (2013). Digitizing the dream: The role of technology in empowering communities. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: Redeem the dream. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp. 130-133. McMillan, M.P. (2016). Relieving the plight of Black male unemployment. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: Message to the president. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, online: http://soba.iamempowered.com/2016-executive-summary Morial, M., Wilson, V.R., Richardson, C., & Clark, T. (2010). Putting Americans back to work: The national Urban League’s plan for creating jobs. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: Responding to the crisis. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp.41-44. National Urban League (NUL). (2011). A dozen dynamic ideas for putting urban America back to work. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America. Transaction Publishers, pp. 46-52. National Urban League Policy Institute (NUPI). (2012). The 2012 N.U.L. 8-point education and employment plan. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America. Transaction Publishers, pp. 55-59. Nightingale, D.S. (2010). Intermediaries in the workforce development system. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: Responding to the crisis. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp.85-91. Nightingale, D.S. & Sorenson, E. (2006). The availability and use of workforce development programs among less-educated youth. In R. Mincy, Black Males Left Behind. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, pp. 185-210. Rawlings-Blake, S. (2014). Baltimore. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America: One nation underemployed, jobs rebuild America. Silver Spring, MD: Transaction Publishers, pp. 62-64. Sharpe, R.V. (2011). America’s future demands a diverse and competitive STEM workforce. In National Urban League (NUL), The state of Black America. Transaction Publishers, pp. 142-152. The Covenant with Black America (2006). Chicago: Third World Press. Workforce Investment Act (WIA) (2018). 29 U.S. code § 2801 - repealed. Pub. L. 113–128, title V, § 511(a), July 22, 2014, 128 Stat. 1705. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/29/2801  Figure 1: African American Twitter Use. Source: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/01/06/african-americans-and-technology-use/ Figure 1: African American Twitter Use. Source: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/01/06/african-americans-and-technology-use/ Written by Serie McDougal and Sureshi Jayawardene In 2014, the Pew Research Center reported that “African Americans have long been less likely than whites to use the internet and to have high speed broadband access at home” which they claimed continues to be the case. This gap between Blacks and Whites is most pronounced among subgroups for both races, such as older African Americans and those who have not attended college. Compared to Whites of the same demographic profile, these subgroups are less likely to go online or have broadband service at home. However, other African Americans who are young, college-educated, and earn a higher income are on equal footing with their White counterparts in terms of internet use and broadband adoption at home. Although African Americans trail Whites in terms of internet use and high-speed broadband access at home, this “digital divide” is less persistent when it comes to types of access. African Americans have exhibited elevated levels of digital literacy and use, especially through mobile platforms. According to the Pew report, 96% of African American internet users between the ages 18-29 use a social networking platform of some kind. Twitter is particularly popular among this demographic. Colloquially known as “Black Twitter,” the social and political currency generated by African American Twitter users underscores the autonomy and credibility afforded to this bloc of social commentators producing results from awareness-raising about issues facing Black communities to influencing important decisions shaping the world (see Figure 1). Examples of such leverage and mobilization include #BlackLivesMatter, #SayHerName, #BankBlack, and #OscarsSoWhite movements that have yielded national dialogue about issues of civic and political importance. The 2016Nielsen report highlights how this demographic—African American millennials—are “driving social change and leading digital advancement.” Specifically, and further supporting Pew’s findings two years prior, Nielsen reports that African American millennials are impacting the tech industry through their increasing use of mobile devices. According to Nielsen, young African Americans’ expanding use of smartphones contributes to increased online activity in the areas of shopping for beauty products, apparel, fresh and healthy foods, primetime television viewership, and other such consumer behaviors. This demographic is not only savvy about the everyday functionality of online consumer behaviors such as these but are just as “adept at using and leveraging digital platforms to communicate with each other and the world around them.” Although African Americans quickly adopt and leverage new digital technologies with great ease and efficacy, they remain underrepresented in the digital workforce. African Americans represent less than five percent of the workforce in most technology companies, according to the National Urban League’s 2018 State of Black America (SOBA) report (NUL, 2018). Making matters worse, the high-tech industry has significantly less workforce diversity than other STEM areas like Telecom (Cravins, 2018). It is important to highlight that the SOBA report does point out that the underrepresentation of Black people in the tech industry is also a consequence of racial bias in hiring practices (Johnson, 2018). Without addressing the underrepresentation of African Americans in the digital economy, the SOBA 2018 report warns that already deep gaps in digital racial equity or tech-equity will only widen. For example, the wave of automation (automatic equipment limiting or eliminating the need for human involvement in processes) threatens to eliminate workers in certain jobs (i.e. bus drivers, cashiers, cooks, and fast-food workers) (Spencer, 2018). Twenty-seven percent of African Americans are concentrated in the jobs most vulnerable to automaton (Spencer, 2018). New technological products are not only changing people’s access to products and services, they are changing ways of living. These changes have not only impacted how people engage one another through technology, but how integrated certain technologies are in their everyday lives. Without a doubt, African Americans have effectively leveraged social media and creatively used it as a tool for social justice movements. And while Nielsen emphasizes the need to better engage the $162 billion buying power of African American millennials in their digital consumption, it is just as important to attend to the inequities and disparities apparent in the digital workforce. The National Urban League’s position is that righting the wrongs of the past and establishing racial equity are dependent upon the efforts of private, government, and corporate sectors. Their hope is to lure the tech industry to invest in racial equity with the fresh voices and talent they could benefit from it. This fatally flawed logic is impaired by a simple failure to account for the fact that the United States of American has always been willing to absorb aggregate losses incurred by inequity for the racialized power and privilege it awards individuals who self-identify as White or at-least non-Black/African. Works Cited Cravins, D. (2018). Smart cities, inclusive growth: Harnessing the enormous economic promise of next generation networks. In the National Urban League (NUL) (2018). State of Black America: Powering the digital revolution. Retrieved from http://soba.iamempowered.com/soba-books Johnson, N.F. (2018). Minding the gap: Connecting diversity with Diverse IT. In the National Urban League (NUL) (2018). State of Black America: Powering the digital revolution. Retrieved from http://soba.iamempowered.com/soba-books National Urban League (NUL) (2018). State of Black America: Powering the digital revoution. Retrieved from http://soba.iamempowered.com/soba-books Neiderdorff, M. (2018). Embracing and engaging the possibilities of the digital revolution. In the National Urban League (NUL) (2018). State of Black America: Powering the digital revolution. Retrieved from http://soba.iamempowered.com/soba-books Overton, S. (2018). Black to the future: Will robots increase racial inequality. In the National Urban League (NUL) (2018). State of Black America: Powering the digital revolution. Retrieved from http://soba.iamempowered.com/soba-books Written by Serie McDougal

Chetty, Hendren, Jones, & Porter (2018) investigated an age-old social science notion, the notion of racial disparities. What could possibly be revealed about it that is not already known? Social science might be described as a process of systematically discovering, explaining, and understanding that which is already known and experienced in other ways. European social science and political mantra have included the axiom that the primary obstacle to social advancement is class and not race. Chetty, Hendren, Jones, & Porter (2018) decided to test this western conventional wisdom by asking the question: do Black children have lower incomes than white children conditional on parental income, and if so, how can we reduce these intergenerational gaps? To answer this question, they examined data from the 2000 and 2010 decennial Censuses linked to data from federal income tax returns and the 2005-2015 American Community Surveys to obtain information on income, race, parental characteristics, and other variables. Their sample included 20 million children, approximately 94% of the total number of children in the birth cohorts we study. They looked at children’s incomes as their mean household income in 2014-15, when they are in their mid-thirties and parents’ income as mean household income between 1994 and 2000, when their children are between the ages of 11 and 22. They found that intergenerational mobility and persistence varied significantly by race. Latinx Americans and Asian Americans were found to move up in income across generations. Even Black people born into high income families are more likely to experience downward mobility compared to Whites. However, when the researchers accounted for gender differences, they found that although the Back-White income gap was the largest in their analysis, it was entirely driven by the gap between Black and White men. The researchers explain: Put differently, when we compare the outcomes of Black and White men who all grow up in two-parent families with similar levels of income, wealth, and education, we continue to find that the Black men still have significantly lower incomes in adulthood. The last family-level explanation we consider is the controversial hypothesis that differences in cognitive ability explain racial gaps. Although we do not have measures of ability in our data, three pieces of evidence suggest that differences in ability do not explain the persistence of Black-White gaps for men. First, the prior literature (e.g., Rushton and Jensen 2005) suggests no biological reason that racial differences in cognitive ability would vary by gender. Therefore, the ability hypothesis does not explain the differences in Black-White income gaps by gender. Second, Black-White gaps in test scores – which have been the basis for most prior arguments for ability differences – are substantial for both men and women. The fact that Black women have incomes and wage rates comparable to White women conditional on parental income despite having much lower test scores suggests that tests do not accurately measure differences in ability (as relevant for earnings) by race, perhaps because of stereotype threat or racial biases in tests (Steele and Aronson 1995; Jencks and Phillips 1998). Third, we show below that environmental conditions during childhood have causal effects on racial disparities by studying the outcomes of boys who move between neighborhoods, rejecting the hypothesis that the gap is driven by differences in innate ability. (Chetty, Hendren, Jones, & Porter, 2018, p. 5) Black boys who grow up in high-income families and low poverty neighborhood are more likely than White boys to have lower incomes in adulthood. But what factors lead to stability or improved mobility? Among Black males in low poverty neighborhoods who did experience better outcomes across generations, the two factors associated with smaller Black-White gaps were: low levels of racial bias among Whites and high rates of father presence among Blacks. The researchers found that low-income neighborhood father presence (defined as being claimed as a child dependent by a male on tax forms) was associated with better outcomes among Black boys, but uncorrelated with the outcomes of Black girls and White boys. This relationship was found at the neighborhood level regardless of whether or not the father was a child’s biological fathers. The presence of fathers (biologically related or not) was found to be associated with better outcomes for Black boys. They also found that Black boys who move to better neighborhoods also experience higher incomes and less incarceration than those who don’t. Overall their research suggests that Black boys who move to neighborhoods with lower poverty rates, White with levels of racial bias, and high rates of father presence among Black residents tend to experience better outcomes. The problem: less than 5% of Black boys grow up in such places. The research is said to have debunked the notion that the primary challenge African Americans face is class and not race. As Ibram X. Kendi states, “One of the most popular liberal post-racial ideas is the idea that the fundamental problem is class and not race, and clearly this study explodes that idea, but for whatever reason, we’re unwilling to stare racism in the face” (Riley, 2018). According to Chetty, Hendren, Jones, & Porter (2018), solving this problem will require policies “whose impacts cross neighborhood and class lines and increase upward mobility specifically for black men” (p.7). Chetty, Hendren, Jones, & Porter (2018) suggest policies that cannot be expected to solve these intergenerational problems alone are those that include cash transfers, increases in minimum wage, policies that reduce residential segregation and produce school integration. Instead, what is needed are targeted programs for Black boys specifically and policies that improve conditions within specific schools and neighborhoods (Chetty, Hendren, Jones, & Porter, 2018, p. 5). Although it is unsurprisingly left unstated, the data seem to provide a rationale for increased effort and resources behind single gender Afrocentric independent and charter schools targeted toward Black male student populations. Although the report suggests programs to reduce racial bias among Whites, looking at the situation through the lens of the colonial paradigm, Black populations would be ill-advised to embrace this as a strategy for advancement given that racial bias among Whites is a commodity from which white identified populations receive power and privilege. Waiting for White people to make the choice to abandon that which provides them power and privilege would not serve the interests of Black boys or Black communities. Nevertheless, the ability of race to trump class for Black people in general and Black males specifically remains a lived reality awaiting its Christopher Columbus like discovery by the research community. Moreover, as significant as this new research is, it remains one in a long train of social science discovery moments as the humanity of people of African descent come in and out of visibility to the research community. Before this realization fades from memory and visibility it is critical the people of African descent build programs to specifically address in the needs of Black boys with culture grounding and targeted focus. Works Cited Badger, E., Miller, C. C., Pearce, A., & Quealy, K. (2018). Rich White boys stay rich. Black boys don't. Retrieved March 31, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/19/upshot/race-class-white-and-black-men.html Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Jones, M.R., & Porter, S.R. (2018). Race and economic opportunity in the United States: An intergenerational perspective. Retrieved from http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/assets/documents/race_paper.pdf Riley, P. (2018, March 20). Report: Wealthy Black boys have a greater chance of living in poverty than middle class White boys. Retrieved March 23, 2018, from https://newsone.com/3784420/black-boys-class-white-racism/ Written by Sureshi Jayawardene and Serie McDougal

“African American mothers are dying at three to four times the rate of non-Hispanic white mothers, and infants born to African American mothers are dying at twice the rate as infants born to non-Hispanic white mothers.” This is a statement made in the Center for American Progress’s (CAP) recent report exploring the high rates of infant and maternal deaths among African Americans. Although some have suggested that the problem could be explained by Black mothers’ greater likelihood of being poor and less educated compared to White women, they found that this trend remained true across socioeconomic and education levels. Whatever their backgrounds, all African American mothers share experiences of racial and gender discrimination, which recent research shows, induces stress that can affect infant and maternal mortality. Even with notable Black women like Erica Garner and Serena Williams, pregnancy-related complications played a role in their own health. In Garner’s case, the two heart attacks she suffered after the birth of her son in August 2017 ultimately took her life at the end of that year. For the relatively powerful, healthy, and wealthy Serena Williams, while her pregnancy itself was easy, her daughter was born by emergency C-section because Williams’s heart-rate fell dramatically low. Currently, maternal and infant mortality rates in the US represent a significant racial disparity. This racial gap has been consistent since the government and hospitals began collecting this data more than 100 years ago. According to CAP, in more than 50 years, not much has changed. It is the higher rates of preterm births and low birth weights among African American women that drives this gap. CAP discusses how the typical risk factors such as physical health, socioeconomic status, prenatal care, and maternal health on their own are insufficient to explain the high incidence of the high rates of infant and maternal death among African Americans. Turning their attention to the role that racism plays in these outcomes, CAP concludes that chronic exposure especially during sensitive periods in early development can better explain these rates for African Americans. There are distinct developmental trajectories that set African American women apart from other racial groups, especially non-Hispanic Whites. According to CAP, “the social and economic forces of institutional racism set African American and non-Hispanic white women on distinct life tracks, with long-term consequences for their health and the health of their future children.” Some of these developmental setbacks experienced by African American families compared to non-Hispanic White families include:

The “life course perspective” is a necessary and important intervention in this area of research because the experience of systematic racism produces profound and lifelong effects for African American families. The relationship between racism and the life span can also be explained using data for Black immigrant women—from the Caribbean and the African continent—who arrive in the US as adults and experience better birth outcomes than native-born African American women. For native-born African Americans, the continuous experience of racism can lead them to experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (emotional stress, physical harm, and fear) (Evans, Hemmings, Burkhalter, & Lacy, 2016). Racism can cause African Americans to evaluate themselves negatively based on externally imposed standards which can lead to depression. African American women must face gendered racism targeted at them because they are Black women. Experiencing this stress can lead to frustration, anger, hopelessness, and hypertension. Physiologically, it can increase cortisone levels in a pregnant mother, which can: trigger labor and/or cause inflammation restricting blood flow to the placenta and stunting infant growth (Carpenter, 2017). According to Carpenter (2017) it is not just racial stress experienced during pregnancy, “stress throughout the span of a woman’s life can prompt biological changes that affect the health of her future children. Stress can disrupt immune, vascular, metabolic, and endocrine systems, and cause cells to age more quickly” (p.14). Addressing this problem requires moving beyond a deficit approach that focusses almost exclusively on Black women’s health choices and behaviors and genetic factors. Advocacy movements such as Black Mamas Matter Alliance and the National Birth Equity Collaborative are making strides in raising public awareness through racial and reproductive justice campaigns. Despite these efforts, there needs to be more research that uncovers better data on Black women’s health disparities alongside more continuous, systematic reviews of maternal and infant death. CAP suggests comprehensive, nationwide data collection on maternal deaths and complications, research that substantiates the mother’s health before, during, and between pregnancies, data sets that include information about environmental and social risk factors, assessment and analyses on the impact of overt and covert racism on toxic stress, research that identifies best practices and effective interventions for improving the quality and safety of maternity care, and research to identify effective interventions for addressing social determinants of health disparities. We at Afrometrics support these recommendations and add that what is needed is a culturally relevant research program that not only examines more critically the role that racism plays throughout the life span, but also accounts for the specific cultural values and needs of African American mothers. Works Cited Carpenter, Z. (2017). “Black births matter.” The Nation, 304(7), 12-16. Evans, A. M., Hemmings, C., Burkhalter, C., & Lacy, V. (2016). “Responding to race related trauma: counseling and research recommendations to promote post- Traumatic growth when counseling African American males.” Journal of Counselor Preparation & Supervision, 8(1), 78- 103. Lambert, S., Robinson, W., & Ialongo, N. (2014). “The role of socially prescribed perfectionism in the link between perceived racial discrimination and African American adolescents’ depressive symptoms.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(4), 577-587. Written by Serie McDougal

Having just celebrated Kwanzaa, it is rewarding to reflect on what the Nguzo Saba (seven principles of Kwanzaa) have offered to ceremonies and rituals for peoples of African descent. Beyond the week-long Kwanzaa holiday itself, the Nguzo Saba provides a value structure for Black schools, businesses, social services, and most especially rites of passage. Belgrave, Allison, Wilson & Tademy (2011) developed a cultural enrichment program for Black boys called “Brothers of Ujima.” The third principles of the Nguzo Saba, Ujima is the Kiswahili word which means collective work and responsibility. The purpose of the “Brothers of Ujima” program is to take a strengths-based approach to Black male development by enhancing positive aspects of their selves and identities such as self-esteem, ethnic identity, pro-social behaviors, and positive development. Furthermore, the program seeks to reduce negative behaviors. Graves & Aston (2018) investigated the intervention. They determined that the 14-week program was grounded in the Nguzo Saba. The format involves organizing the boys into Jamaas (Kiswahili for families). Wazees, or respected elders, who are mentors and members of the facilitation team are selected to facilitate each jamaa. The curriculum is divided into 14 sessions designed to achieve the following objectives:

The Impact of “Brothers of Ujima” Qualitative analyses based only on observation of the program and interviews with the parents of boys who had participated in the program suggest that the boys formed positive fatherly relationships with the group leaders; the boys felt open enough to voluntarily share their school successes and failures with groups leaders; the physical activities they engaged in taught them self-discipline, and; mothers spoke of how the program changed their sons’ lives (Belgrave & Brevard, 2015). A different examination of the program in a school setting investigated the effects of the “Brothers of Ujima” program on a group of boys labeled “at-risk” and referred to the program for a documented need for emotional and behavioral support (Graves & Aston, 2018). The investigators measured how the program specifically impacted the boys’ internalization of Afrocentric values (i.e. principles of the Nguzo Saba), their resilience, and their sense of racial identity (the degree to which an individual feels a connection with and an attachment to their racial group based on a common history and shared values). The results showed that the program actually increased the boys’ Afrocentric values but had no significant effect on their racial identities or senses of resiliency. The authors speculate that this may be due to the fact that the results were based on the boys’ self-reported evaluations of the impact of the program. Critical Evaluation of “Brothers of Ujima” The initial evaluation of “Brothers of Ujima” was limited because it was only based on observation and interviews with parents instead of a pretest and posttest experimental design. The program would benefit greatly from some quantitative evaluation, with larger populations, building on the qualitative work that has already been done. Another concern that arises from the curriculum is its seeming lack of explicit focus on boyhood, manhood, or masculinity, which are important elements in development for boys. This may be a possible missed opportunity for how “Brothers of Ujima” has been implemented. Graves & Aston’s (2018) study of “Brothers of Ujima” was done in a school setting on a group of students who had been referred due to disciplinary problems such as suspension and expulsions. This may signal another problem at the level of program implementation. If “Brothers of Ujima” is targeted at groups of males who are exhibiting problem behaviors, this goes against one of the tenets of the program’s original design which is to organize the boys into diverse groups of Black males to enhance their exposure. This is an example of how deficit thinking can be used in otherwise African centered programming. Black males exhibiting problem behavior in some areas of their lives can benefit from Black males who are not, and vice versa. Those who are excelling in school can benefit from rites of passage as much as those who are not, but most importantly they can benefit from one another. However, the “Brothers of Ujima” program is among the most promising rites of passage programs available that have been exposed to some level of empirical evaluation. This is truly a testament to the creators of the program and their desire for improvement and embrace of critical assessment. Works Cited Belgrave, F. & Brevard, J. (2015). African American Boys: Identity, Culture, and Development. New York: Springer. Belgrave, F. Z., & Allison, K. W. (2014). African American psychology: From Africa to America. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications. Belgrave, F. Z., Allison, K. W., Wilson, J., & Tademy, R. (2011). Brothers of Ujima: A cultural enrichment program to empower adolescent African American males. Champaign: Research Press. Graves, S., & Aston, C. (2018). A mixed‐methods study of a social-emotional curriculum for Black male success: A school‐based pilot study of the Brothers of Ujima. Psychology in the Schools, 55(1), 76-84. Written by Serie McDougal

Goff, Jackson, Di Leone, Culotta, Ditomasso (2014) conducted a study examining the extent to which Black boys are perceived as children compared to other boys. They found that Black boys were perceived as older and less innocent compared to White same age peers. Building on the study about Black males, Epstein, Blake & Gonzalez (2017) recently published a study adults’ views of Black girls as less-innocent and adult-like compared to White girls. The study consistent of an innocence questionnaire measuring adultification applied to White girls and one to Black girls. Three-hundred-and-twenty-six participants were randomly assigned to a questionnaire about their perceptions of Black girls or White girls. The results indicated that Black girls were perceived as developmentally older, needing less nurturing, needing less protecting, needing less support, more knowledgeable about sex and adult topics compared to White girls. The authors explain the implications of these results in the context of how they affect how Black girls are treated in the education and criminal justice systems. When Black girls are seen by school officials as older and less in need of support, this may explain why they experience disproportionate school disciplining because they are viewed as more culpable for their actions leading to more harsh punishments. School disciplining such as suspensions can increase the likelihood of arrest and dropping out of school The authors apply the same logic to (Epstein, Blake & Gonzalez (2017). The authors also explain that this ideology influences the disproportionate treatment of Black girls referred to law enforcement; particularly more harsh punishments in the juvenile justice system. The authors admit that the study doesn’t go as far as it could in explaining the implications. The implications of this study are much more far reaching that the education and criminal justice systems that the authors mention. If Black girls are removed from their child development trajectory and presumed more adultlike compared to their peers, this is likely to have implications on how they are treated in the healthcare system, religious institutions, ROTC, parenting, social welfare policy, and in the media to name a few. This methodologically sound article can be built upon with implicit bias studies and experimental designs which are better suited to establish causation on comparison to the questionnaire approach that was used. Moreover, the National Association of Black Social Workers and the National Association of Black Psychologists and similar organizations are well suited to developed counseling practices, intervention strategies, and suggested parenting practices to preempt and prepare Black girls to maintain their confidence, and to be successful and protected in hostile environments that remove the normal societal protections afforded to children. Lastly, the discipline of Africana Studies is in a key position to take the lead in the development of the current body of research on Black girlhood. This critical work is already underway by emerging young scholars like Ms. Jewell L. Bachelor who recently completed the study: Reclaiming Black girlhood: An exploration into sexual identity and femininity. The development of a body of research will provide practitioners with the data necessary to guide effective practices to mitigate the effects on the dehumanization that Black girls face. References Bachelor, J. L. (2016). Reclaiming Black girlhood: An exploration into sexual identity and femininity. San Francisco State University, Master’s Thesis. Epstein. R., Blake, J.J. & Gonzalez, T. (2017). Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of Black girls’ childhood. Georgetown Law: Center on Poverty and inequality. Goff, P., Jackson, M., Di Leone, B., Culotta, C., Ditomasso, N. (2014). The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526-545. Healing, from an Afrocentric perspective, is the effort to maintain a state of balance between physical, mental, social, and spiritual aspects of reality. My question is, where do the politics of herb fit? Today several states in the U.S. allow both recreational and medicinal use of marijuana, including: Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. Even more, allow medicinal use of marijuana. What role does marijuana use play in the healing of Black men from racism? A new 2017 study investigated the relationship between the experience of discrimination and marijuana use among adult Black men (Parker, Benjamin, Archibald & Thorpe, 2017). Why? Because Black males report experiencing more chronic and acute racial discrimination throughout their lives than Black women (Parker, Benjamin, Archibald & Thorpe, 2017). Moreover, they have begun to have their first experiences with marijuana smoking earlier in life. The researchers used survey data from 1,271 Black men who participated in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) from 2009.

Black male participants reported how often they smoked marijuana. To make the survey more interesting, the researchers measured two kinds of experiences with racism: everyday racism and major racism. Everyday Racism was measured by having the men complete the Everyday Discrimination Scale, which asked the men about a) being treated with less courtesy than others; b) being treated with less respect than others; c) receiving poorer services than others; d) being treated as if they are not smart by others; e) others being afraid of them; f) being perceived as dishonest by others; g) people acting like they were better than them; h) denied a loan; i) feeling threatened or harassed; j) being followed in stores more than others. The researchers measured Major Racism by having the men answer questions about whether they were ever unfairly a) fired; b) not hired; c) denied promotion; d) treated/abused by the police; e) discouraged from continuing education; f) prevented from moving into a neighborhood; g) neighbors made life difficult; h) denied a loan; i) received poor service from a repairman. The results showed that experiencing everyday racism was not associated with marijuana use. However, major discrimination was associated with marijuana use. The more the men experienced major discrimination the more they reported smoking marijuana. The men who reported smoking marijuana the most (every day in the last 12 months), had a decreased risk of experiencing major discrimination. But what does this mean? According to the authors, everyday discrimination is commonly related to increased marijuana use among non-Black ethnic groups. However, it may be that because Black men have more experienced with discrimination, they have become accustomed to these experiences and are not as affected. The authors explain that major discrimination was probably associated with increased marijuana use among Black men because it has a major effect on their livelihoods, their abilities to be providers, and their connectedness to society’s institutions. The authors argue that smoking marijuana may have been a way of escaping or alleviating the negative emotions associated with major discrimination. One finding that almost goes unaddressed in this study is the fact that men who reported smoking marijuana the most (every day in the last 12 months), had a decreased risk of experiencing major discrimination. Perhaps, future research might explore why. Nevertheless, there are a range of possible reasons, including social withdrawal from institutions where major racism may occur to a change of perspective or outlook. The study also does not consider competing explanations for the relationship between major discrimination and marijuana use, like a rejection of social norms that make both discrimination and the rejection of marijuana normal. Although the researchers, Parker, Benjamin, Archibald & Thorpe (2017), suggest that the marijuana is used to escape or alleviate the negative emotions due to discrimination, could marijuana facilitate much more though? After all, no human behavior is inherently deviant, it only acquires that label in relation to a set of social norms. But whose norms? More and more today, marijuana is being seen as a treatment and less a form of deviance. However, people of African descent have recognized the healing properties of many herbs long before this more recent revolution in “established western medicine”. The healing traditions of many African ethnic groups included those who were herbalists and made use of mixtures of stems, seeds, roots, and leaves instilled with spiritual power for the purpose of restoring balance and harmony (Osanyin among the Yoruba and Inyanga among the Zulu). During slavery, Black people in the South regularly went to conjurers and root-workers who provided them with health services grounded in the use of spiritual power and herbal treatment (Savitt, 1987). Given that informal group healing making use of marijuana is not uncommon, what role might it play in formal healing interventions. People find different ways of making sense of racist experiences and dealing with the stress that may come from those experiences. Utsey, Adams & Bolden (2000) define Africultrual coping as “as an effort to maintain a sense of harmony and balance within the physical, metaphysical, collective/communal, and spiritual/psychological realms of existence” (p.197). There are four primary components of Africultural coping: cognitive/emotional debriefing is an adaptive reaction that African Americans use to manage perceived environmental stress, such as discussing a racist co-worker with a supervisor, seeking out someone who might make one laugh and holding out hope that things will get better; spiritual-centered coping methods, like praying, represent African Americans sense of connection to spiritual aspects of the universe; collective coping, grounded in a collectivist value system, is the use of group-centered activities to manage perceived racial stress, like getting a group of family or friends together to discuss; ritual-centered coping involves the use of rituals such as acknowledging the role that ancestors play in life, celebrating events, and honoring religious or spiritual deities. Ritual-centered coping might also involve playing music or lighting candles. Constantine, Donnelly & Myers (2002) found that the more African American adolescents believed that their cultural group was a significant part of their self-concept, the more they were likely to use coping methods such as collective and spiritual-centered coping to deal with stress. What role does spirituality play in Black males use of marijuana? It is important that future research examines how effective integrating marijuana into formal healing interventions for Black males might be. Works Cited Constantine, M. , Donnelly, P. , & Myers, L. (2002). Collective self-esteem and africultural coping styles in African American adolescents. Journal of Black Studies, 32(6), 698-710. Parker, L. , Benjamin, T. , Archibald, P. , & Thorpe, R. (2017). The association between marijuana usage and discrimination among adult black men. American Journal of Men's Health, 11(2), 435-442. Utsey, S. , Adams, E. , & Bolden, M. (2000). Development and initial validation of the africultural coping system inventory. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(2), 194. |

Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed